Our planetary science researcher Professor Sara Russell explains the origins of Earth’s closest companion.

An astronaut aboard the International Space Station captures the full Moon as it sets behind Earth's horizon. Image © NASA via NASA Image and Video Library

Analysis of samples brought back from the NASA Apollo missions suggest that Earth and the Moon are the result of a giant impact between an early proto-planet and an astronomical body called Theia.

Moon origin theories

“There used to be a number of theories about how the Moon was made and it was one of the aims of the Apollo program to figure out how we got to have our Moon,” Sara explains.

Prior to the Apollo mission research there were three theories about how the Moon formed. The evidence returned from these missions gave us today’s most widely accepted theory.

- Capture theory suggests that the Moon was a wandering body – like an asteroid – that formed elsewhere in the solar system and was captured by Earth’s gravity as it passed nearby.

- The accretion hypothesis proposes that the Moon was created along with Earth at its formation.

- The fission theory suggests Earth had been spinning so fast that some material broke away and began to orbit the planet.

- The giant-impact theory is most widely accepted today. This proposes that the Moon formed during a collision between Earth and another small planet, about the size of Mars. The debris from this impact collected in an orbit around Earth to form the Moon.

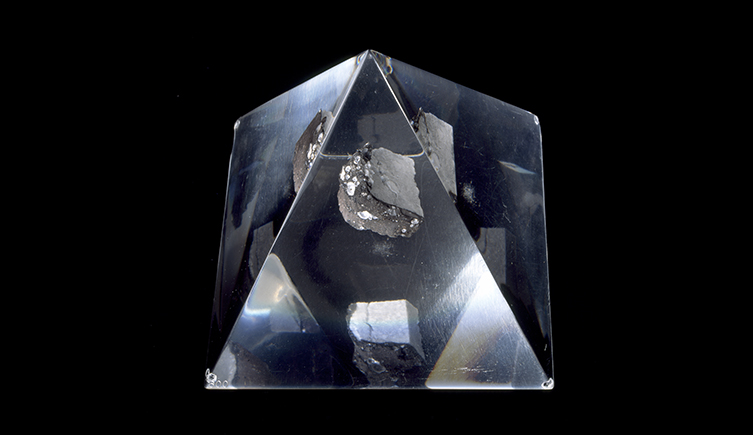

Lunar meteorite Dar al Gani 400. In 1998, this specimen was found in the Sahara Desert, in Libya.

Moon rocks from the Apollo missions

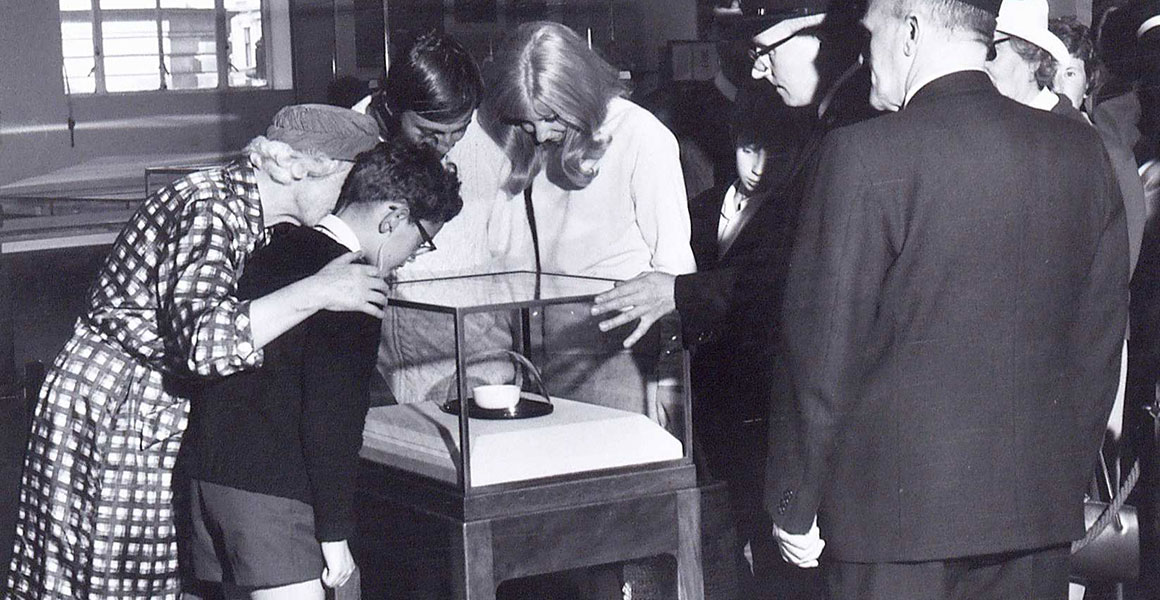

The Apollo missions, which ran during the 1960s and 1970s, brought back more than a third of a tonne of rock and soil from the Moon. This lunar material provided some clues on how the Moon may have formed.

“When the Apollo rocks came back, they showed that Earth and the Moon have some remarkable chemical and isotopic similarities, suggesting that they have a linked history,” says Sara.

“If the Moon had been created elsewhere and was captured by Earth’s gravity we would expect its composition to be very different from Earth’s.”

“If the Moon was created at the same time, or broke off from Earth, then we’d expect the type and proportion of minerals on the Moon to be the same as on Earth. But they’re slightly different.”

This thumbnail-sized piece of Moon rock was gifted to the Natural History Museum by President Nixon in 1973. It was collected during the last Apollo space mission. Find out more about our links to the Apollo missions.

The minerals on the Moon contain less water than similar terrestrial rocks. The Moon is rich in material that forms quickly at a high temperature.

“In the seventies and eighties there was a lot of debate, which led to an almost universal acceptance of the giant impact model,” says Sara.

Lunar meteorites are also an important source of data for studying the origins of the Moon.

“In some ways meteorites can tell us more about the Moon than Apollo samples because meteorites come from all over the surface of the Moon, while Apollo samples come from just one place near the equator on the near side of the Moon.”

Proto-Earth and Theia

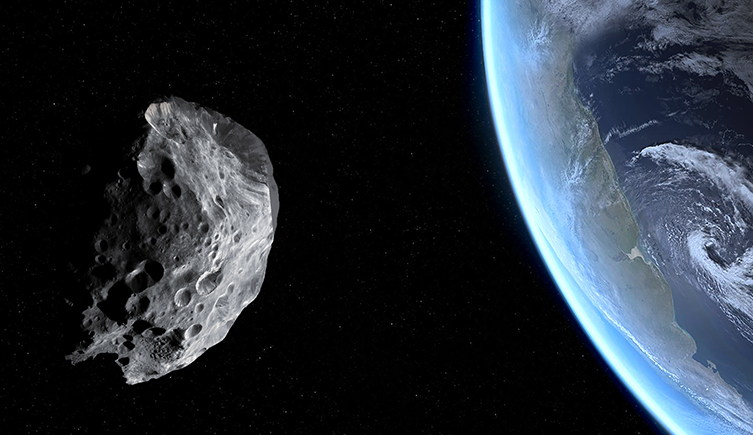

Before Earth and the Moon, there were proto-Earth and Theia, which was a roughly Mars-sized planet.

The giant-impact model suggests that at some point in Earth’s very early history, these two bodies collided.

The Moon may have formed in the wake of a collision between an early proto-planet and an astronomical body called Theia. © Fernando Astasio Avila/ Shutterstock

During this massive collision, nearly all of Earth and Theia melted and reformed as one body and a small part of the new mass span off to become the Moon.

Scientists have experimented with modelling the impact, changing the size of Theia to test what happens at different sizes and impact angles, trying to get the nearest possible match.

“People are now tending to gravitate towards the idea that early Earth and Theia were made of almost exactly the same materials to begin with, as they were within the same neighbourhood as the solar system was forming,” explains Sara.

“If the two bodies had come from the same place and were made of similar stuff to begin with, this would also explain how similar their composition is.”

The surface of the Moon

The mineralogy of Earth and the Moon are so close that it’s possible to observe Moon-like landscapes without jetting off into space.

“If you look at the lunar surface, it looks pale grey with dark splodges,” Sara says. “The pale grey is a rock called anorthosite. It forms as molten rock cools down and lighter materials float to the top, and the dark areas are another rock type called basalt.”

Professor Sara Russell explains what the dark spots on the Moon are.

Similar anorthosite can be seen on the Isle of Rum in Scotland. What’s more, most of the ocean floor is basalt – it’s the most common surface on all the inner planets in our solar system.

“However, what’s really special on the Moon, that we can’t ever replicate on Earth, is that the Moon is geologically rather dead,” Sara says.

The Moon hasn’t had volcanoes for billions of years, so its surface is remarkably unchanged. This is also why impact craters are so clear.

By looking at the Moon we can tell a lot about what Earth was like four billion years ago.

Professor Sara Russell explains more about the Moon's formation:

A balancing influence

Having a moon as large as ours is something that’s unique in the solar system.

“While other planets have tiny moons, Earth’s Moon is almost the size of Mars,” Sara says.

“If you look at other similar planets to ours, they wobble quite a lot in their orbit – the North Pole moves – and as a result the climate is much more unpredictable.”

A piece of anorthosite breccia Moon rock displayed in a glass prism.

The Moon has helped stabilise Earth’s orbit and reduced polar motion. This has aided in producing our planet’s relatively stable climate.

“It’s a subject of quite a lot of scientific debate as to how important the Moon has been in making it possible for life to exist on Earth,” explains Sara.

Find out how the Moon affects life on Earth.

Does Earth have more than one moon?

There may indeed be several objects in orbit around Earth. But to the best of our knowledge they’re objects that the planet has drawn into its orbit – most likely captured asteroids. These natural satellites don’t share the same important history as the Moon and they likely exist only temporarily in Earth’s orbit.

See a piece of the Moon

You can find a lunar rock specimen in our Earth Hall and see the Apollo Moon rock we care for in our Treasures gallery.

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet before our exhibition’s mission ends.

Closes Sunday 22 February 2026

Prepare for liftoff knowledge seekers!

But hold onto your helmets. Did you know we’re offering an on-demand course about Rocks in Space? Get ready to expand your knowledge to infinity and beyond.

Explore space

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Discover more

Last chance to visit our Space exhibition!

Don’t miss your opportunity to snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet!

Until Sunday 22 February 2026

Last chance to visit our Space exhibition!

Don’t miss your opportunity to snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet!

Until Sunday 22 February 2026

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media