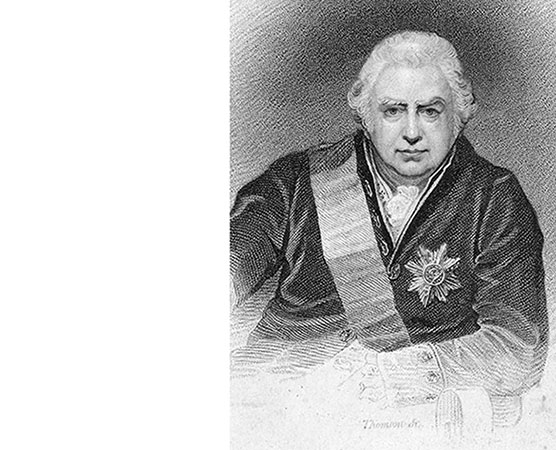

Official portrait of Sir Joseph Banks as President of the Royal Society, 1812

undefinedJoseph Banks: scientist, explorer and botanist

Kerry Lotzof

Combining a passion for botanical knowledge and an inherited fortune, Joseph Banks encouraged and patronised scientific activity all over the world.

His vast collection of plants and animals are vital to the Museum's scientific collections, for both scientific research and our understanding of Britain's colonial past.

The early life of Joseph Banks

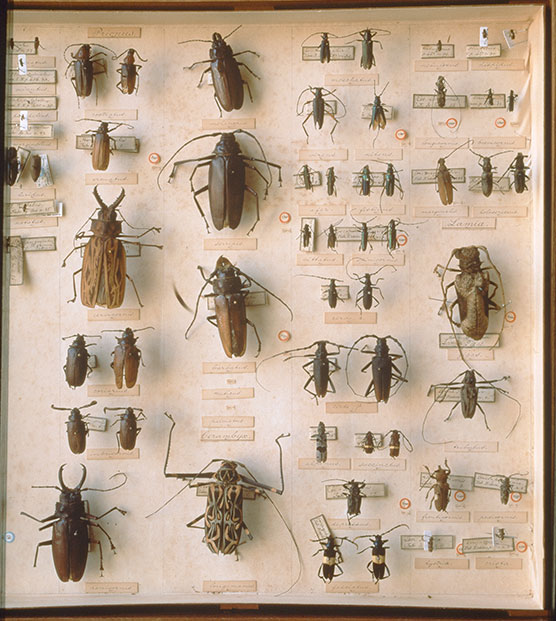

Tray of beetles including many longhorn beetles from the collections of Sir Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks (1743-1820) was born on 13 February 1743 in Lincolnshire. His father, William Banks, was a wealthy landowner.

As a child, he enjoyed the outdoors and developed a passion for natural science at a young age. He was educated at Eton College and the University of Oxford, and left in 1763 with an extensive knowledge of natural history.

At 21, having inherited the impressive estate of Revesby Abbey in Lincolnshire, Banks became one of England's wealthiest men, with an income of £6,000 per year - more than £1 million pounds in today's money.

With a thirst for knowledge and the means to pursue it, Banks took his first voyage of discovery at the age of 23.

Newfoundland and Labrador (HMS Niger)

In 1766 Banks joined HMS Niger, travelling under the command of Sir Thomas Adams.

The purpose of the journey was to transport a party of mariners to build a fort and survey the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, today Canada's most easterly province.

As the ship's botanist, Banks collected many species of plants and animals previously unknown to Western science. Two weeks after his return to the UK, he was admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

He caught the attention of the scientific community by publishing the first Linnean descriptions of the plants and animals of Newfoundland and Labrador. He also documented many new species of birds, including the great auk, which subsequently went extinct in 1844 from overhunting for its feathers, meat and oil.

Great auk (Pinguinus impennis) specimen. See one on display among the Treasures in the Cadogan Gallery>

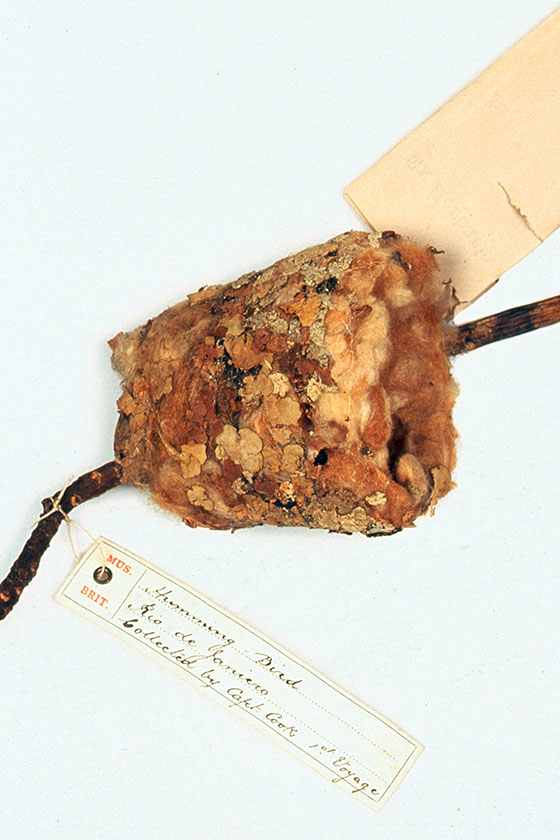

Hummingbird nest collected by Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander in Rio de Janeiro during Captain Cook's first voyage, 1768

The South Pacific (HMS Endeavour)

A few years later, Banks persuaded the admiralty to allow him to join an expedition led by James Cook to the South Pacific. In 1768, the crew of HMS Endeavour set out to explore and chart the lands of the South Pacific and record any territory, plants and other resources that might be of use to the British Empire.

The voyage circumnavigated the globe, visiting South America, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Java.

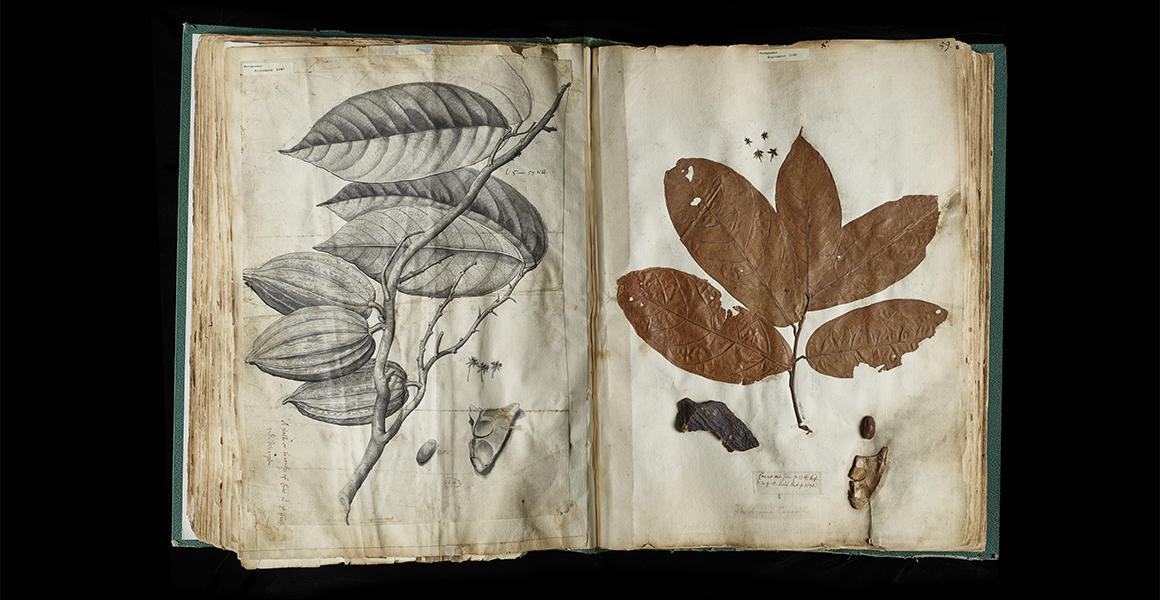

With the help of collectors and artists such as Daniel Solander and Sydney Parkinson, Banks accumulated an enormous trove of knowledge and specimens, including more than 1,000 plant species previously unknown in Europe.

Old man banksia (Banksia serrata) specimen alongside an illustration by Sydney Parkinson. Banks brought thousands of new species to the attention of Western science, including acacia, eucalyptus and banksia, a genus named in his honour.

Out of their party of nine, only Banks, Solander and two servants survived - the rest succumbed mostly to shipborne illnesses. On their return to England in 1771, the men became heroes of the London scientific community.

Iceland (Sir Lawrence)

The following year, Banks led Britain's first-ever scientific expedition to Iceland.

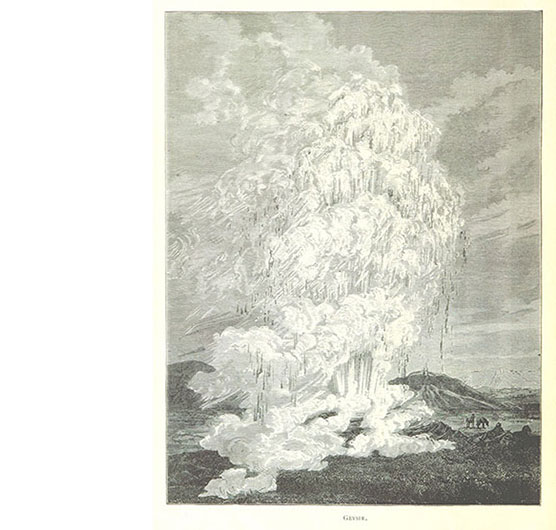

In his journal, Banks described the dramatically spouting hot springs as 'volcanoes of water'. The term 'geyser' was coined later, after Geysir, one of the most impressive Icelandic hot springs. Illustration by Frederick Howell, 1893. Image courtesy of the British Library on Flickr.

He was due to join Captain Cook's second voyage, which was planned to circumnavigate the globe as far south as possible to determine whether there was any other great southern landmass. But after a fiery disagreement with the admiralty about his proposed living quarters and scientific provisions, Banks resolved to fund his own expedition instead.

A growing interest in volcanology among fashionable Londoners inspired him to explore new heights. He then chartered the Sir Lawrence and a crew of 12 to transport himself and his team to Iceland.

Among the members of the expedition were three artists: John Cleveley Jr, James Miller and his brother John Frederick Miller. They departed England on 12 July 1772, the same day that Cook began his second voyage.

The focus of the expedition was to climb and observe Hekla - a famous Icelandic volcano - and measure the spouting hot springs.

After six weeks in Iceland, Banks and his crew returned to England with hundreds of illustrations and specimens recording the geology, flora and fauna of the region, as well as a collection of Icelandic manuscripts.

As a result, Banks became the foremost British expert on Iceland.

Although Iceland would be his final adventure in the field, a more settled life in London didn't limit Banks's impact on British exploration, science or affairs of state - in fact, it was quite the reverse.

A man of influence

After his travels, Banks's influence continued to grow. He settled in London, assembling an enormous library and herbarium at his home in Soho Square.

Engraving depicting 32 Soho Square, the address of Sir Joseph Banks's residence and herbarium. From the Banks Archive at the Natural History Museum, London.

Thanks to this unrivalled collection of plants and books, his home rapidly became one of the scientific and social centres of Georgian London.

Banks made his unique collections open to anyone who wished to examine his plants and books. He also maintained an extensive network of correspondence with friends and scientific colleagues all over the world.

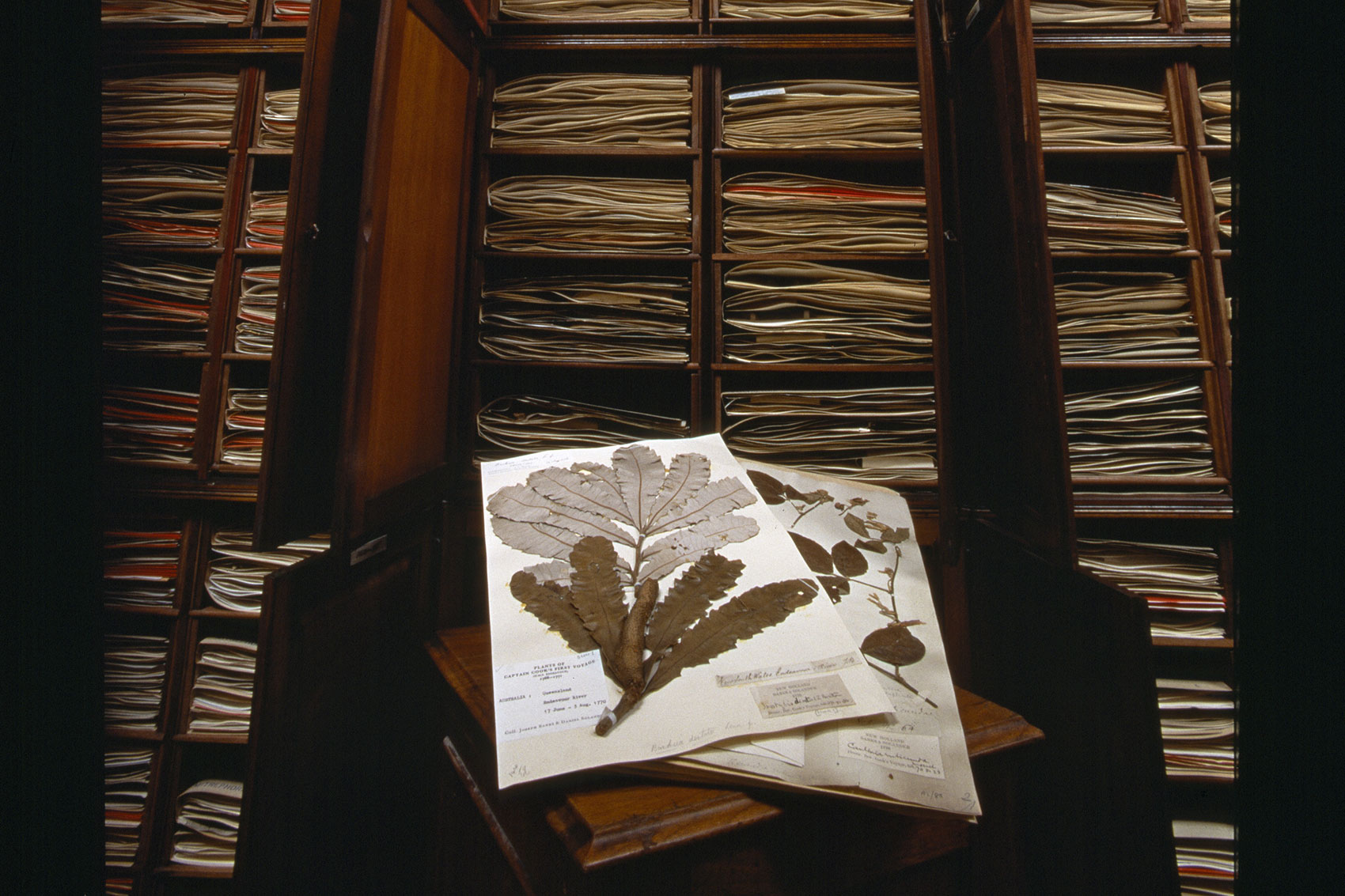

Banksia dentata and other herbarium specimens housed in Sir Joseph Banks's original cabinets installed in the present-day herbarium

Banks became a trustee of the British Museum and King George III's advisor for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, which flourished under his care to become one of the most comprehensive botanical gardens in the world.

He sent explorers and botanists all over the world, looking for new and economically useful species that could be cultivated on British lands.

Sir Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks was made a baronet in 1781 and a Knight Commander of Bath in 1795 for his patronage of natural science.

Drawer of butterflies from the insect collection of Sir Joseph Banks - a collection of more than 4,000 insects, including butterflies, flies, bugs and moths

In 1778 he was appointed President of the Royal Society, a position which he held for 41 years, making him the longest-standing president on record.

In this role Banks fostered good relations between scientists across Europe and America, despite this being a time of political turmoil and conflict between nations. He was known for strongly endorsing scientific exploration and oversaw many voyages.

One voyage he helped arrange was William Bligh's infamous trip on HMS Bounty, now better known for its mutiny. Bligh's mission had been to collect breadfruit from Tahiti for cultivation as a cheap food source for enslaved people on British plantations in the West Indies.

By transplanting species between countries and continents, Banks saw his influence transform entire landscapes and economies. He was also an outspoken supporter of slavery, which he considered vital to the wealth and economic power of the British Empire.

Explore research into how the Museum's history and scientific collections are connected to the transatlantic slave trade>

Watercolour illustration of the breadfruit plant (Artocarpus altilis) prepared by Sydney Parkinson on board HMS Endeavour, 1769

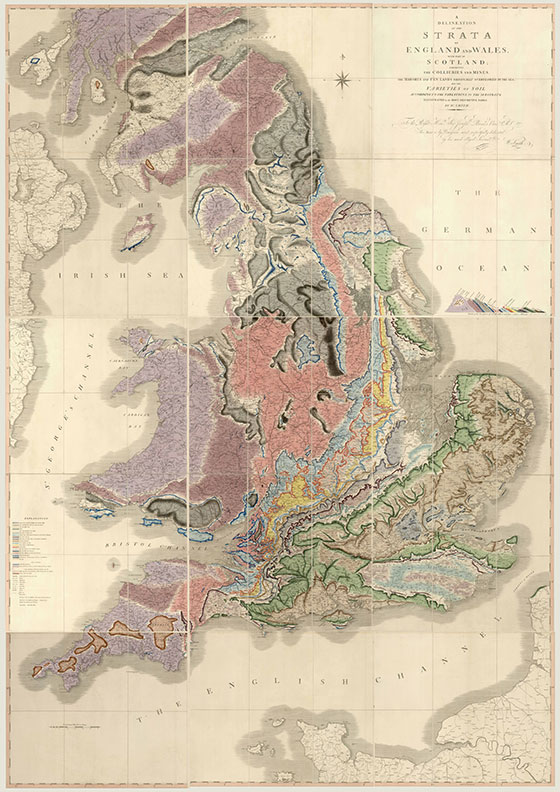

Banks was a major financial supporter of William Smith in his decade-long efforts to create the first geological map of England

Banks was made a member of the Privy Council in 1797, acting as adviser to successive governments and King George III. In this role he had a direct impact on many important affairs of state.

Official portrait of Sir Joseph Banks as President of the Royal Society, 1812

During the Napoleonic Wars he acted on behalf of the people of Iceland when they were deprived of trading rights by the British. He also championed the British colonisation of Australia and advocated to make Botany Bay the site of a penal settlement.

Joseph Banks died in London in 1820 at the age of 77. On his death, his collections and library were left to Robert Brown, his librarian and a respected natural scientist. In 1827 they were transferred to the British Museum, where Brown was appointed to the position of Keeper of the Banksian Botanical Collections.

Banks's legacy

Approximately 110 new genera and 1,300 new species were named from the specimens Banks collected in his lifetime. Some 75 different species bear his name, as do a group of islands near Vanuatu in the South Pacific, and a peninsula in New Zealand.

As the longest-serving president of the Royal Society he set the course of British science for the first part of the nineteenth century. He was also a founding member of the Linnaean Society, the Royal Institution and the Royal Horticultural Society.

Illustration of a Merino sheep (Ovis aries). One of Joseph Banks's most famous scientific papers was titled 'Some circumstances relative to Merino Sheep', published 1809. It discussed the benefits the breed could offer to improve British wool production.

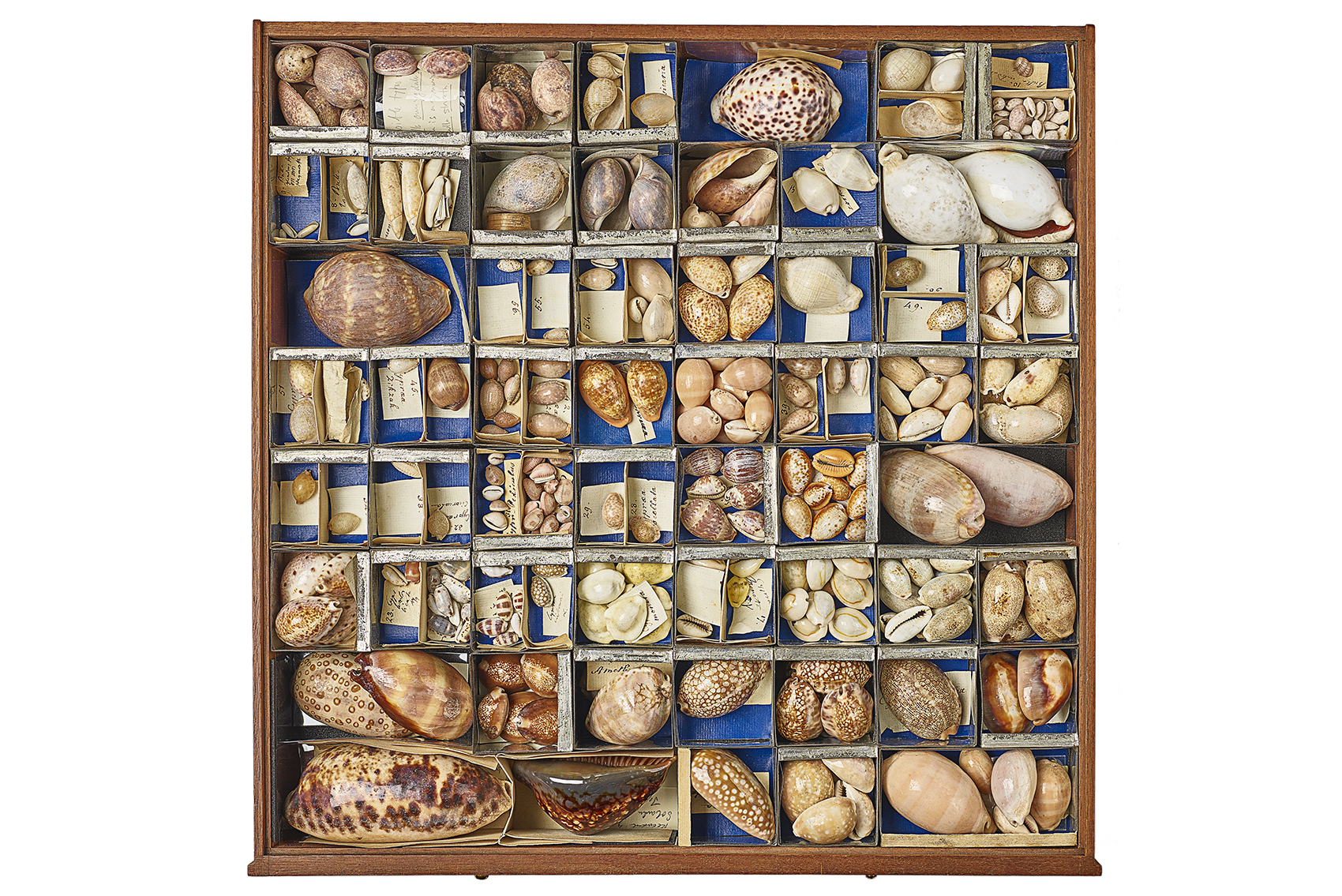

Today Banks's botanical collection is housed at the Museum, along with more than 4,000 insects and other specimens. His private collection forms a cornerstone of the Museum's botanical collections, its significance rivalled only by the contribution of Sir Hans Sloane.

Banks's collections can be accessed online using the Museum's online database.

The Museum Library and Archives are also home to special collections of Joseph Banks's natural history illustrations as well as many original manuscripts, letters and correspondence.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media