When you think about sharks, the first thing that might come to mind are huge jaws filled with rows of deadly-looking teeth.

But shark teeth come in many shapes and sizes. They can tell us how these fish live and evolved.

Mako sharks have needle-like teeth. They use them to grip onto their food, such as fish and cephalopods. © Jessica Heim/ Shutterstock

When you think about sharks, the first thing that might come to mind are huge jaws filled with rows of deadly-looking teeth.

But shark teeth come in many shapes and sizes. They can tell us how these fish live and evolved.

All sharks have teeth, but what may surprise you is that they don’t all have sharp, triangular teeth.

“Sharks have been around for 420 million years,” explains Emma Bernard, our Fossil Fish Curator.

“In that time, there have been as many as 5,000 different species. One of the reasons sharks have been so successful is that they’ve exploited different ecosystems and eaten different types of foods. And because they’re eating different foods, they need different types of teeth.”

There are four basic types of shark teeth.

Great white sharks have upper teeth with tiny serrations along their edges. © Alessandro De Maddalena/ Shutterstock

Serrated teeth have a jagged edge – a bit like the blade of a bread knife. Sharks don’t chew, so this combination of pointed lower teeth and serrated upper teeth helps them to cut prey into smaller pieces for swallowing.

Great white sharks have this combination of teeth. These apex predators eat sea lions, dolphins and even other sharks.

A shortfin mako shark head from our spirit collection. This species of shark has needle-like teeth.

Long, sharp teeth are excellent at gripping small or medium-sized fish and squid. The bull shark has needle-like teeth that are slightly serrated, for example. They mostly eat fish, but will also catch turtles and other species of sharks.

Some needle-like teeth, such as those of the tasselled wobbegong, are straight. Others are curved and can be used to hook prey, such as those of hooktooth sharks.

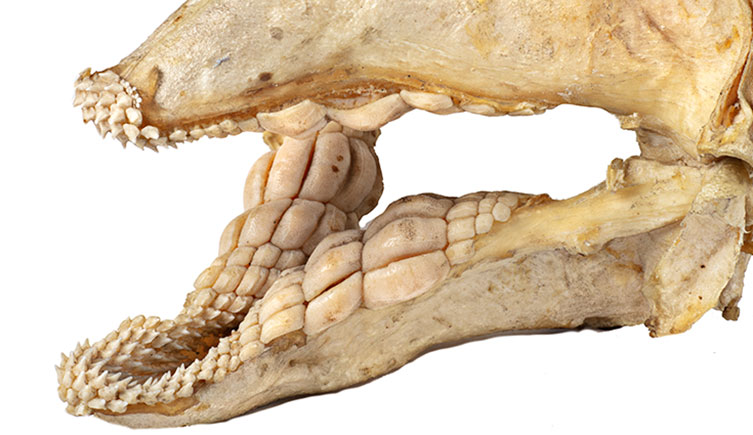

The jaws of a Port Jackson shark. These sharks have small, grasping teeth at the front of the mouth and flat, crushing teeth at the back.

Some sharks have teeth that are flat and very strong. They’re typically found in species that live at the bottom of the ocean and feed on hard-shelled animals such as crabs and shelled molluscs. Examples include the nurse shark, the angel shark and the Port Jackson shark.

The Ptychodus sharks that lived during the Cretaceous Period had teeth shaped like the round cap of a mushroom, which they used to crush ammonite shells.

Whale sharks have tiny teeth, but they don’t use them for catching food. © Rich Carey/ Shutterstock

Some sharks feed by sucking water in through their mouths. Small organisms such as plankton get stuck in their gill rakers and the shark then consumes the food.

Filter-feeding sharks include whale sharks, megamouth sharks and basking sharks. These species have teeth, but they’re largely vestigial – meaning they once served a purpose but over time the animal has evolved to no longer rely on them.

Non-functional teeth are often very small. Whale sharks have 300 rows of teeth that are less than six millimetres long. They also have tiny teeth covering their eyeballs!

The variety of shark teeth and their functions demonstrates that not all sharks are the fearsome predators of film and television.

“Sharks get really bad press and for the most part it’s unfair,” says Emma.

“Sharks are responsible for killing about 10 people a year. By contrast, humans are responsible for killing about 100 million sharks a year.”

The average modern shark tooth is usually between about 1.3-5 centimetres long. Female sharks typically have larger teeth than males. Tooth size also varies depending on where they are positioned in the jaw.

Great white shark teeth reach up to five centimetres long. Yet even these long gnashers pale in comparison to the largest known shark teeth – those of the extinct megalodon, whose name means ‘big teeth’. Megalodon teeth could reach almost 18 centimetres long, within a jaw large enough to swallow a small car.

A fossilised megalodon tooth compared with that of a modern great white shark. Megalodon went extinct around 3.6 million years ago.

On average, sharks have between 50 and 300 teeth arranged in up to 10 rows.

Some sharks lose teeth every few weeks; for others it might take several months. In some cases, when a shark loose a tooth it can be replaced within 24 hours.

“Usually, it’s only the first few rows of teeth which are involved in feeding,” Emma explains.

“The rows of teeth push forward so that when one tooth falls out, there’s another ready to replace it, like a conveyor belt. By replacing their teeth regularly, they ensure their teeth remain useable so they can eat.”

In this way, some species of shark can go through 30,000 teeth in their lifetime.

In species such as the cookiecutter shark and the kitefin shark, they’ll lose the entire lower plate of teeth in one go. Sometimes the shark will swallow the tooth plate along with its meal. It’s thought this helps the shark to maintain healthy calcium levels.

Geneticists are studying how sharks continually produce new teeth to explore if this genetic trait could help doctors grow human teeth in the future.

This lower jaw belonged to a kitefin shark. It shows its replacement teeth waiting in the wings. © Alessandro De Maddalena/ Shutterstock

Sharks’ teeth are made from a very hard substance called enameloid, covering a core of dentine. These components make shark teeth very hard, like bone.

Sharks also have some enamel in their vertebrae and in hard bumps embedded in their skin, called dermal denticles.

Our fish curator Dr Rupert Collins explains why some fish use sharks as livingscratching posts. Watch this video with audio description (2 minutes 10 seconds).

When a shark sheds a tooth, it usually falls to the seabed where it can be covered by sediment.

“If you get the right conditions and it gets buried very quickly, by layers of mud and sand building up, this can prevent oxygen and bacteria from reaching it,” says Emma

“Over thousands and sometimes millions of years, water trickles through, picking up minerals along the way. When these minerals reach the tooth, a chemical reaction takes place, which slowly turns the tooth into a fossil.”

The colour of a shark tooth fossil will depend on the minerals present in the sediment. For example, if the tooth is fossilised in an area containing iron oxide it will turn teeth an orange colour. This process is called permineralisation.

This megalodon tooth from our collection was found in phosphate beds in South Carolina, USA. The minerals present in the sediment in which it fossilised have turned this tooth black.

Sharks belong to a group of fish called Chondrichthyes. Their skeletal structure is made from a light, flexible material called cartilage rather than bone.

Cartilage breaks down more easily than bone and doesn’t fossilise well.

As a result, most of what we know about extinct species of shark we know from looking at their fossilised teeth.

“Palaeontologists can look at fossil teeth and compare them to modern teeth to work out what sharks were feeding on millions of years ago and understand how they might have interacted with their ecosystem,” Emma explains.

Fossil teeth also help us to understand shark evolution.

For example, we know that the extinct giant mako shark, Isurus hastalis, is the ancestor of today’s great white shark. The fossil record reveals a transitional species called Carcharodon hubbelli, which has teeth that are wide and flat like mako shark teeth but that are also slightly serrated like the teeth of great white sharks. This discovery helped us understand the evolutionary journey that resulted in one of the world’s most famous species of shark.

Sharks have been regularly shedding teeth for millions of years, so it’s not surprising that shark teeth are the most abundant vertebrate fossil.

If you’re hunting for teeth and fossils on the beach, search the shoreline at low tide. Sift through sand with your hands to uncover teeth sitting beneath the surface. If you find a white tooth, it’s likely that it belonged to a modern shark. If it’s darker in colour, it could be a fossil.

The rules for collecting fossils can vary depending on the country, region or even the specific location you are searching in.

In some places fossil collecting may not be allowed at all, or you may need permission from a landowner before you start looking.

Make sure you familiarise yourself with and follow the rules that apply to your area.

If you’re lucky enough to find lots of teeth and fossils, make sure to leave some for others to find.

Explore life underwater and read about the pioneering work of our marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media