The Triassic was a time of change, a transition from a world dominated by mammal-like reptiles to one ruled by dinosaurs.

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

The Triassic Period: the rise of the dinosaurs

Josh Davis

The Triassic Period was a time of great change.

Bookended by extinctions, this era saw huge shifts in the diversity and dominance of life on Earth, ushering in the appearance of many well-known groups of animals that would go on to rule the planet for tens of millions of years.

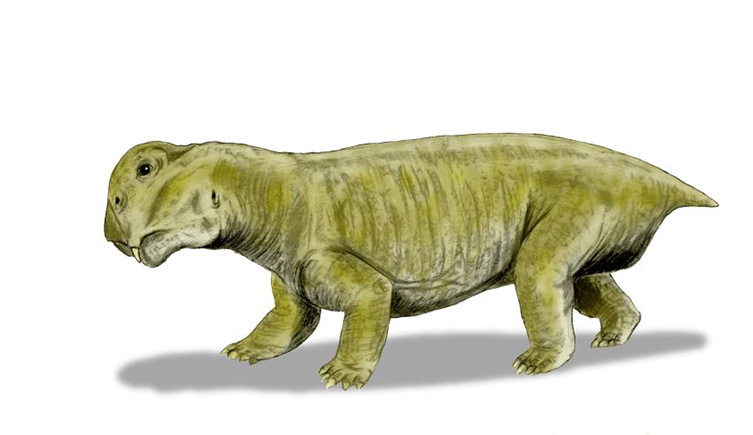

The early Triassic was dominated by mammal-like reptiles such as Lystrosaurus.

Image © Nobu Tamura via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

The Triassic Period (252-201 million years ago) began after Earth's worst-ever extinction event devastated life.

The Permian-Triassic extinction event, also known as the Great Dying, took place roughly 252 million years ago and was one of the most significant events in the history of our planet. It represents the divide between the Palaeozoic and the Mesozoic Eras.

Dr Mike Day is the curator of fossil reptiles at the Museum.

He says, 'The Triassic is an interesting period. It forms the transition between the late Palaeozoic Era, which was mainly populated by synapsids, or mammal-like reptiles, and the Mesozoic Era, when the archosaurian reptiles, which includes the dinosaurs, came to dominate.'

Permian-Triassic extinction: the Great Dying

The cause of the Permian-Triassic extinction event is not fully understood. Various theories have been proposed, such as an unknown asteroid impact, massive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia, the release of methane from the depths of the oceans, sea level change, increasing aridity, or a combination of many of these.

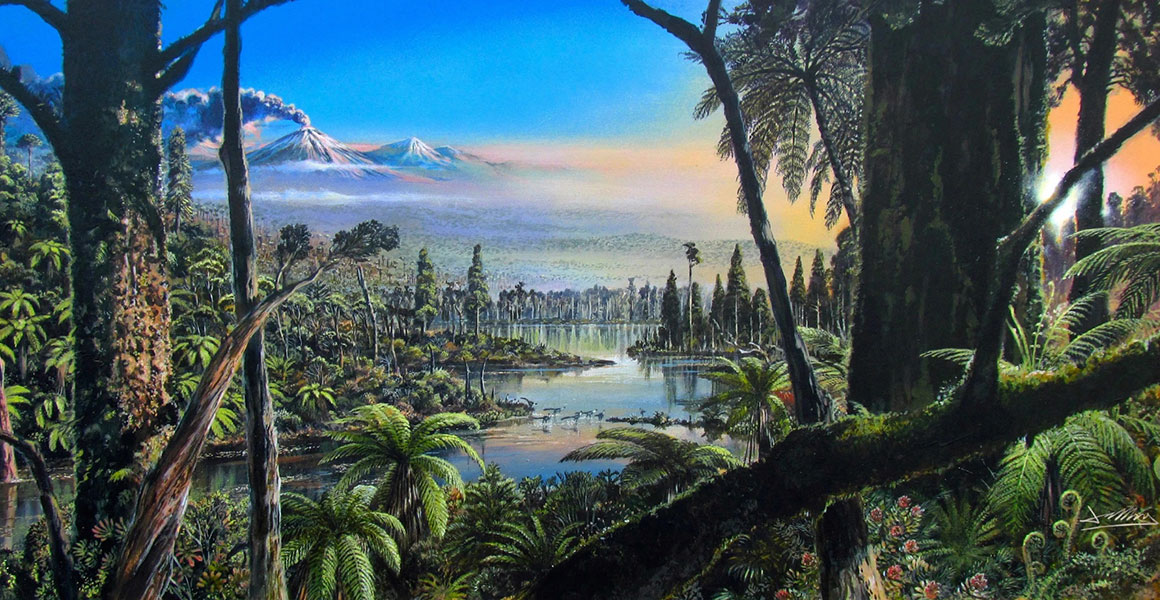

The environment was dominated by conifers, ferns and a now-extinct group of plants known as the seed ferns, or the Pteridospermatopsids. Find out more about our palaeobotany collection.

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Today we tend to think of ferns as preferring dark, damp environments, but in the Triassic they had an incredible array of forms.

Image © Carl Campbell via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

However the extinction event started, the result was catastrophic for large swathes of life.

By some estimations, the Great Dying was responsible for the extinction of up to 90% of all species. It wiped out many groups of insects, large numbers of mammal-like reptiles, and killed off all the trilobites, a group of animals that had existed in the oceans for close to 300 million years.

Dr Paul Kenrick is a researcher at the Museum who specialises in fossil plants. He explains that it was not just the animals that suffered heavy losses during the Great Dying.

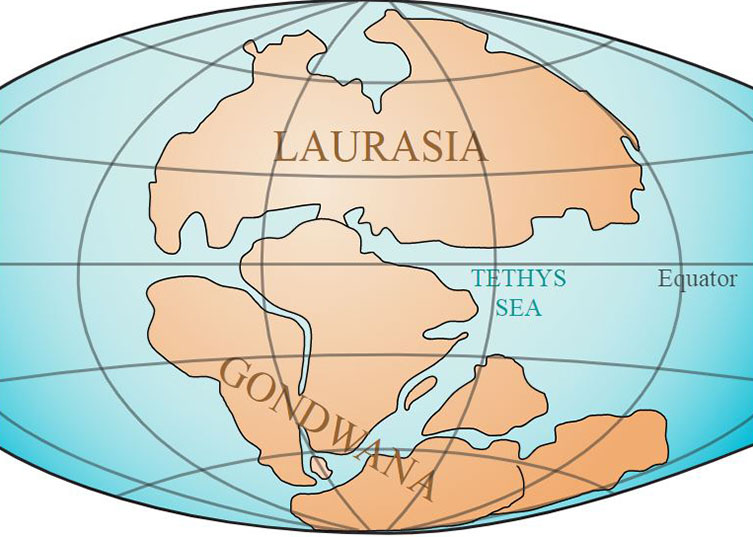

The continents formed a single giant landmass known as Pangea.

Image © United States Geological Survey via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

'What we see when we come through into the Triassic is a re-establishment of ecosystems,' says Paul. 'The first few million years of the Triassic is marked by an absence of coals. This is thought to be related to the mass extinction that happened and the time it took for the recovery of plants.'

This sequence is known as the coal gap, a period in which there was seemingly no coal being laid down. As coal is formed from plant matter that has decayed into peat, it has been suggested that the absence of coal in the first few millions of years of the Triassic was a direct result of the Permian-Triassic extinction event, as plants slowly became re-established in the landscape.

By some estimates, it may have taken up to 10 million years for the planet to recover from the devastation caused by the Great Dying.

The supercontinent Pangea

The Triassic is largely defined by extinctions, but it is also characterised by the position of the continents at that time. There was only one giant landmass: Pangea.

'One might think that because you had this big land mass joined up that the environment across it would be very similar,' says Paul. 'But it's not. There were still quite a lot of differences between the flora in the northern and southern parts.

'Pangea was an extraordinary thing and we haven't seen the like of it since.'

As flowering plants were yet to evolve the planet was dominated by conifers, which grew in an incredible variety of forms.

Image © Max and Dee Bernt via Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

It is during the early part of the Triassic that the conifers took off. With flowering plants and grasses yet to evolve, conifers formed vast forests with individual trees reaching up to 30 metres tall. The understory would have been full of other conifer growth forms that no longer exist today, such as shrubs and woody vines.

'You have to bear in mind that we can reference modern species, but often the form of these extinct plants are either unknown or not completely known,' explains Paul. 'It is difficult to point to a living plant as an example of what they were like.'

Where the environment became drier, the forests gave way to vast fern prairies.

As animal life began to recover, what emerged on land was not so different from what came before. The most common vertebrate on the land was the small, herbivorous synapsid, or mammal-like reptile, called Lystrosaurus.

Ichthyosaurs would come to dominate the oceans of the Jurassic.

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

While these dominated the land, freshwater was the realm of the amphibians. About 250 million years ago, the Lissamphibians (frogs, salamanders and caecilians) were probably only just emerging.

The waterways were instead filled with a different, distinct group of amphibians known as the Temnospondyls. These were much larger animals, some of which grew up to four metres in length. They physically resembled modern crocodiles and likely filled a similar ecological role.

Between 250 and 246 million years ago, the first ichthyosaurs took to the seas, a group which would eventually dominate the oceans. The origin of this successful group of marine reptiles is still not resolved.

While the tuatara may look like a lizard, they are from a distinct lineage known as the sphenodonts.

Image © Bernard Spragg. NZ via Flickr, public domain.

A shift in dominance

Around the same time that ichthyosaurs took the plunge, the first sphenodonts appeared. Represented today by just a single species - the tuatara - they are the sister group to lizards and snakes.

While they look very much like lizards they are in fact a distinct lineage. They were more diverse than the ancestors of modern lizards during the Triassic, performing similar ecological roles that lizards do today.

'During the early Triassic the world was still dominated by mammal-like reptiles, but there was an increasingly important archosaurian component,' says Mike. 'By the end of the Middle Triassic, the synapsids were in decline and a diverse range of archosaurs had appeared. '

The archosaurs were a component of the diapsid lineage, which includes many successful Mesozoic groups such as the dinosaurs and birds, pterosaurs, crocodilians and turtles.

By the Late Triassic there was a shift in dominance between the mammal-like reptiles and the archosaurs. There are various theories as to what may have caused this, such as competition in a climate that was becoming steadily warmer and dryer or evolutionary stagnation. It seems that archosaurs were better able to fill the empty niches left following the extinction of some of the synapsid linages.

Drepanosaurs were truely strange animals, and even today no one is quite sure where exactly they fit on the evolutionary tree.

Image © Nobu Tamura via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

The neck of Tanystropheus was extraordinarily long, equal to the length of its body and tail combined.

Image © Nobu Tamura via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

'There were a lot of weird groups of Triassic archosaurs at this time, such as aetosaurs,' says Mike. 'These were large, armoured animals which looked a bit like some of the armoured dinosaurs that appeared much later.'

Others included the incredibly long-necked Tanystropheus and, potentially, the bizarre chameleon-like drepanosaurs, which had a claw on the end of their tails.

Another successful group was the phytosaurs. These animals looked quite crocodilian, but were from a different branch of the archosaurian tree. The lineage that would give rise to the crocodiles was instead represented in the Triassic by much smaller, more gracile animals.

Dinosaurs in the Triassic Period

It was around 240 million years ago that the first dinosaurs appear in the fossil record. These dinosaurs were small, bipedal creatures that would have darted across the variable landscape.

'Much like today, the environments on Pangea were hugely varied,' says Paul. 'There were parts of the world would have been moist and others that would have been arid.

'The global effect of this supercontinent would have been a greatly enhanced seasonality in different parts of it. There would likely have been an extremely arid interior, but also some very moist and wet temperate and tropical environments too.'

While reptiles were already dominating the oceans and the land, they also took the skies. By 228 million years ago, the first pterosaurs appeared, making them the earliest vertebrates to evolve powered flight.

They would eventually evolve into extraordinary animals with a wingspan of over 15 metres, but the first pterosaurs were much more modest in size with long jaws and tails.

Even though the archosaurs had managed to usurp the synapsids, some still clung on. By 225 million years ago, one branch gave rise to the mammaliaformes, which were likely small, nocturnal insectivores. It is from this group that the mammals would later emerge.

Early mammals were likely nocturnal insectivores, keeping out of the way of dominant archosaurs.

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

While the non-dinosaurian archosaurs continued to dominate most environments, the dinosaurs rapidly started to diversify.

Not long after they first appeared, the dinosaurs may have already diverged into two main groups. These were the Saurischia, which includes the sauropods, and the Ornithoscelida, which includes the theropods and ornithischians.

By the end of the Triassic, some of these early dinosaurs were impressive in size. A few of the first relatives of sauropods, such as Riojasaurus and Lessemsaurus, had already reached over nine metres in length.

The end-Triassic extinction

The first dinosaurs were likely small bipedal predators, but they rapidly diversified.

Image © Nobu Tamura via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

The Triassic ended much as it began.

The climate started to change so that by 201.3 million years ago, Earth experienced another mass extinction event.

The causes of this are still not entirely understood, but what is now the Atlantic Ocean experienced massive volcanic activity. Known as the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP), these eruptions released so much carbon dioxide or sulphur dioxide that is thought to have led to huge climatic upheavals.

The sea levels began to rise and the oceans became more acidic. This is thought to have contributed the dramatic extinctions in the oceans, including the complete eradication of conodonts.

On land, there was significant turnover as terrestrial life also took a massive hit. All Triassic archosaurs, apart from dinosaurs, pterosaurs and crocodiles, went extinct.

This opened up many of the environments that the archosaurs had occupied, paving the way for the surviving dinosaurs to take their place, while the small mammalian relatives still scurried around the forest floors.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media