Our Human Evolution gallery explores the origins of Homo sapiens, tracing our lineage since it split from that of our closest living relatives, the chimpanzee and the bonobo.

Gallery developer Jenny Wong tells us more.

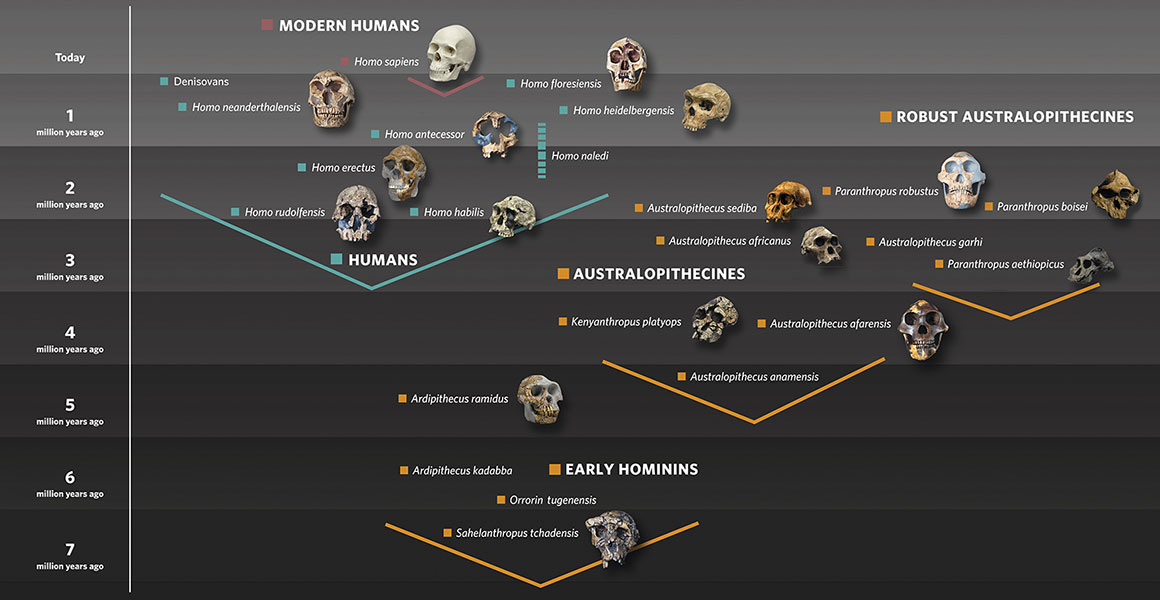

The introduction wall of the gallery displays the diversity of the human family tree using replica skulls belonging to our ancient hominin relatives

Our Human Evolution gallery explores the origins of Homo sapiens, tracing our lineage since it split from that of our closest living relatives, the chimpanzee and the bonobo.

Gallery developer Jenny Wong tells us more.

The gallery takes visitors on an epic journey spanning the last seven million years.

Starting in Africa with our early hominin relatives (who are more closely related to us than to chimpanzees), visitors will travel forward in time to meet our ancient human relatives as they spread into Europe and Asia. The journey ends with modern humans as the only surviving human species in the world today.

Along the way, visitors can see star specimens from the Museum collections, and get to grips with some of the latest research shedding light on our past.

Conservator Effie Verveniotou and human origins researcher Dr Louise Humphrey examine the oldest nearly complete modern human skeleton ever found in Britain before it goes on display in the gallery. Cheddar Man lived around 10,000 years ago.

The story of human evolution is not one of neat, linear progression with a concrete beginning and end. Instead, it is a tale of a family tree whose complex and bushy branches stretch over many millennia and continents. It features a changing cast of ancient hominin relatives, evolutionary dead-ends and many unknowns. Adaptation, survival and extinction provide the dynamic backdrop to this story.

By piecing together fossil traces, scientists are revealing what our ancient relatives were like, how they were related and how they adapted to life in different landscapes and challenging climates.

Entering the gallery, visitors meet hominins like us and our extinct australopithecine relatives, comparing them to non-hominins like the chimpanzee to explore the differences.

The human lineage split from the chimpanzee lineage around seven million years ago. Fossil evidence relating to the earliest hominins that lived after this split is scarce, but it provides important clues about how our ancient relatives lived.

From the six- to seven-million-year-old Sahelanthropus tchadensis skull found in Chad, we know that they had evolved small canines, while six-million-year-old Orrorin tugenensis leg bones show that they exhibited primitive bipedalism (walking on two legs).

Visitors can further investigate the key hominin traits of habitually walking upright and having small canines that aren't used as weapons, using an interactive digital touchscreen.

The 3.5-million-year-old Laetoli canine belonging to Australopithecus afarensis is the oldest hominin fossil in the Museum's collection

Visitors to the gallery will also be able to see a replica of one of the most famous bipedal hominins, the Australopithecus afarensis known as Lucy, who lived around 3.2 million years ago.

By around two million years ago, several australopithecine species like Lucy had evolved and spread across southern and eastern Africa. Fossil remains show that they had adapted to survive in different ecological niches by altering their diets.

Scientists think that some form of australopithecine is likely to have given rise to the next phase of human evolution, the genus Homo.

There have been many species similar to us that have lived over the last two million years. Some co-existed with modern humans in Asia and Europe as recently as 40,000 years ago.

Who these relatives were, and how they lived, is the subject of the next part of the gallery.

Apart from our species, the gallery features eight other kinds of human: Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo erectus, Homo antecessor, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo floresiensis (nicknamed 'the hobbit'), Homo neanderthalensis (the Neanderthals) and the recently discovered Homo naledi. The mysterious Denisovans, who may or may not turn out to be a distinct species, also make an appearance.

Scientifically accurate Homo neanderthalensis model by Kennis & Kennis. Neanderthals survived in Europe until the species went extinct about 39,000 years ago.

Fossil specimens, casts and other objects on display provide a series of snapshots in time, offering visitors glimpses of our ancient relatives' lives.

Exhibits include a flint handaxe possibly made by Homo heidelbergensis and a butchered rhino skull whose brains were extracted and eaten by ancient humans in Sussex, England around 500,000 years ago.

Visitors can investigate a Neanderthal burial and other clues about Neanderthal behaviour, such as innovative tools, which suggest minds capable of creativity and invention.

Coming face to face with a scientifically accurate Neanderthal model, visitors will see how physically adapted they were to cold climates.

The tiny Homo floresiensis highlights another way in which our ancient relatives adapted to their environment, becoming smaller in response to the limited resources available in the island environment of Flores, Indonesia - a process known as island dwarfism.

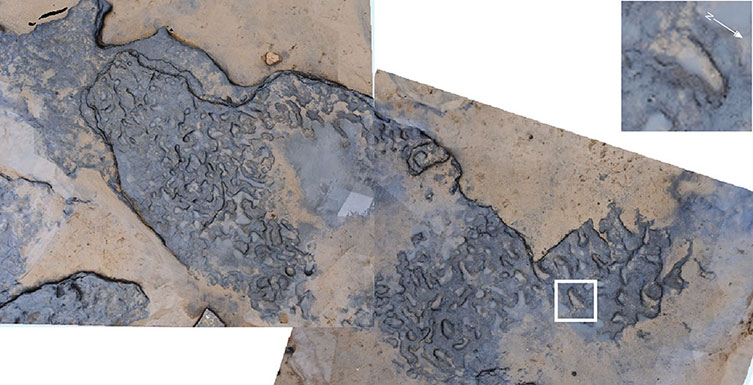

Visitors will encounter some of the exciting research Museum scientists have recently been involved in as part of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain and Pathways to Ancient Britain projects, including the discovery of the oldest human footprints in Europe.

In 2013, erosion of the Norfolk coastline exposed a preserved trail of footprints dating to around 900,000 years ago. Analysis suggests they were left by a small group of humans, perhaps some of the first to set foot in Britain. You can touch a replica footprint in the gallery.

An area of the 900,000-year-old footprints found at Happisburgh, Norfolk, with an enlarged photo of footprint eight showing toe impressions

Other star specimens in this part of the gallery include the Broken Hill skull of Homo heidelbergensis - the first early human fossil found in Africa - and the Gibraltar 1 skull, which was the first adult Neanderthal skull ever found. Gibraltar 1 has recently been sampled for ancient DNA, with the results eagerly awaited.

With advances in the extraction and analysis of ancient DNA and the sequencing of both Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes, scientists are revealing in more detail how our ancient relatives could have looked and behaved. They are also pinpointing what exactly we have inherited from our closest ancient human relatives.

We know that interbreeding with these ancient humans allowed Homo sapiens to acquire genes that improved their chances of survival, and some of these genes remain in many of us today.

Some of the DNA inherited from Neanderthals seems to have been involved in boosting immunity, for example, while a gene variant inherited from Denisovans - present today in Tibetan populations - may enable better survival at high altitudes.

Gibraltar 1, the first adult female Neanderthal skull ever discovered

The final part of the gallery explores how our species, Homo sapiens, originated in Africa, before dispersing around the world and becoming the only surviving species of human left today.

Modern humans evolved in Africa around 200,000 years ago. They have a higher and more rounded brain case, smaller faces and brow ridges, and a more prominent chin than other ancient humans.

Casts on display include modern humans fossils found in Africa (about 195,000 years old), Israel (around 100,000 years old) and Australia (around 12,000 years old).

These fossils show that rather than springing fully formed from Africa, typical modern human characteristics instead built up over time. They also suggest that there may have been at least two waves of migration out of Africa - one dating back to around 100,000 years ago and another to around 60,000 years ago.

Outside of Africa, we are all descendants of those who left in that second wave of migration.

Artefacts in this final zone of the gallery highlight the craftsmanship and ingenuity of modern humans, as well as early symbolism and cultural practices such as cannibalism.

Human skull fashioned into a cup. Museum scientists Dr Silvia Bello and Prof Chris Stringer have been researching cut marks on bones from Gough's Cave in Somerset, England, to understand more about the behaviour of humans who lived there 14,700 years ago.

Human evolution is a puzzle with thousands of fossil pieces and billions of DNA fragments. As new fossils continue to be uncovered and added to the human family tree, new dating techniques and climate data are providing a more accurate picture of the conditions in which our ancient relatives evolved.

Improved DNA techniques will help determine where each species fits within the family tree, and give us further insights into recent and ongoing human evolution.

Museum scientists and collections are playing a key part in shaping one of the most exciting fields in science today. We're delighted to be able to show visitors some of this work in the gallery.

Loan of the Gough's Cave human material to the Museum, including Cheddar Man, is made possible thanks to the generosity of the Longleat Estate.

Museum science is helping to answer where, when and how humans evolved.

Embark on a seven-million-year journey of evolution and see fossil and artefact discoveries in our Human Evolution Gallery.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media