Homo habilis is one of the earliest members of the Homo genus. Initially believed to be the first maker of stone tools, its discovery in 1960 created a continuing controversy around what characteristics make us human.

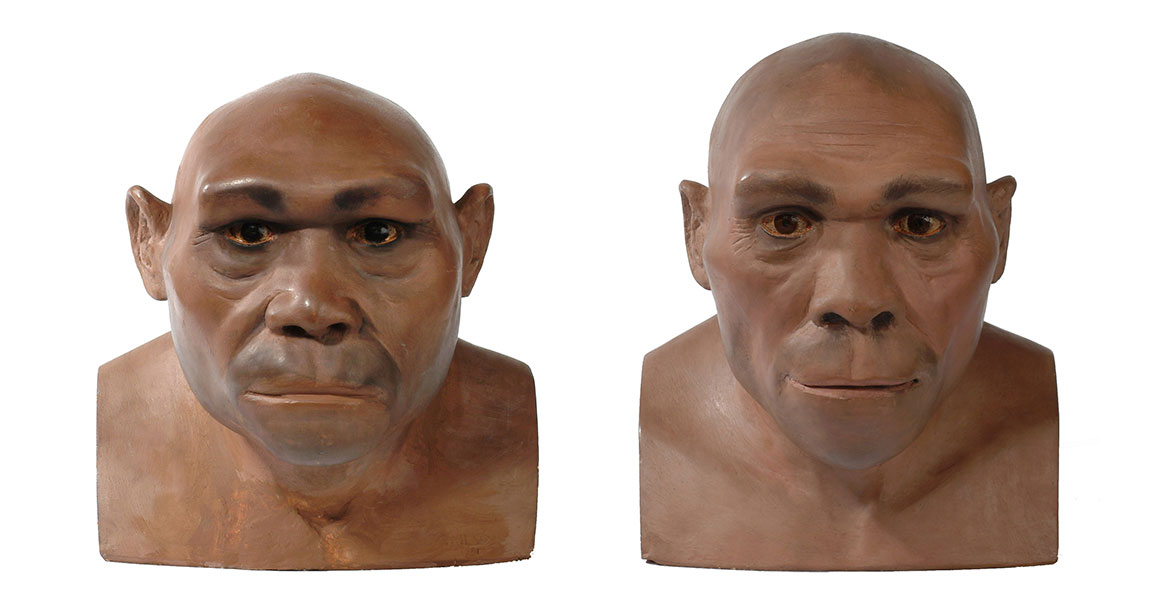

A facial reconstruction of Homo habilis, whose name means handy or skilful human. Fossils of this ancient human species were first discovered alongside stone tools in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, sometimes called Oldupai Gorge. Facial reconstruction. Image © Cicero Moraes via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Homo habilis facts

- Lived: from about 2.0 to 1.6 million years ago

- Where: eastern and southern Africa

- Appearance: small, with short legs and long arms, a relatively large brain and australopith-like jaws and teeth

- Brain size: 500-800cm3

- Height: 1-1.35m

- Weight: about 32kg

- Diet: probably largely vegetarian with some meat when available

- Species named in: 1964

- Name meaning: ‘handyman’ or ‘skilful human’

Who discovered Homo habilis and where was it found?

Famous palaeoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey discovered Homo habilis in 1960. Along with their son Jonathan, they unearthed the first fossils at Olduvai Gorge in the Great Rift Valley of Tanzania, East Africa.

The couple had already found fossils of another primitive hominin species and some early stone tools at the site. The new finds provided evidence of an intriguing new Homo species.

Fred Spoor, one of our Research Leaders in human evolution, explains:

‘Louis and Mary Leakey were looking for the maker of the stone tools they had found. First, they found a rather bizarre heavily built creature with a very flat, upright face not at all like modern humans. It quickly got the nickname Nutcracker Man. They thought this must be the toolmaker.’

‘But the Leakeys then started finding the remains of something that had smaller, more human-like teeth and perhaps a larger brain. They also found hand fossils, which was interesting because the hand is what you use to interact with stone tools. So, they decided this second find was the toolmaker.’

The Nutcracker Man was described as the species Paranthropus boisei and the larger-brained fossil was described as Homo habilis.

View of Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where Homo habilis was first found. The location’s name comes from ‘Oldupai’, a Maasai word meaning ‘place of the wild sisal’. © Oleg Znamenskiy/ Shutterstock

Where did Homo habilis live?

Important Homo habilis fossils have been discovered in Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa. Lake Turkana in northern Kenya yielded a particularly significant collection of fossils.

Unlike our ancient ancestor Homo erectus, Homo habilis didn’t migrate out of Africa, so its fossils aren’t found elsewhere in the world.

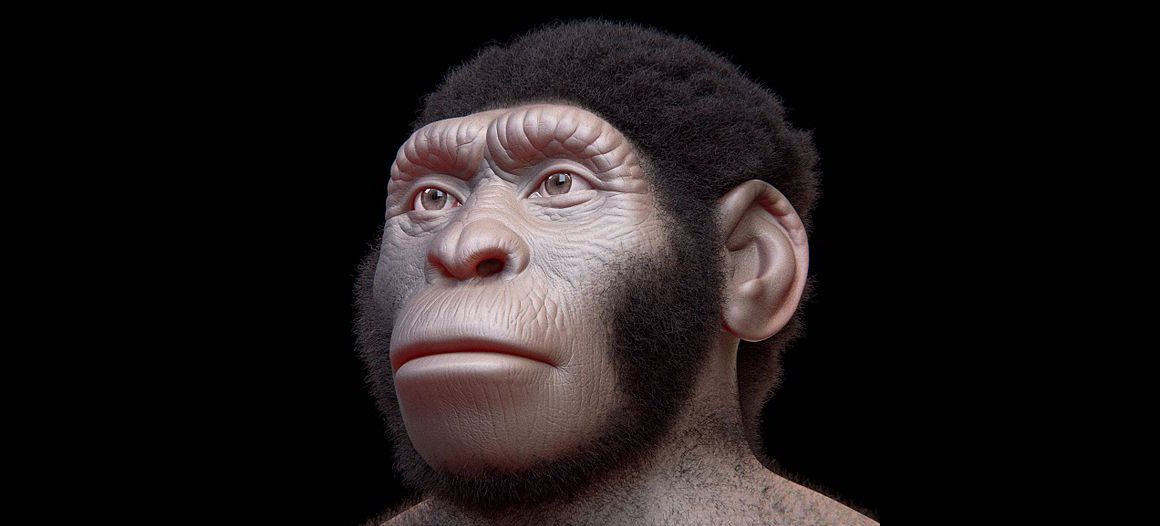

What did Homo habilis look like?

Homo habilis had several rather human attributes. These include a large, thin skull and larger front teeth and smaller back teeth than more ancient human relatives, or hominins. Its finger bones suggest the ability to form a precision grip, a key human trait.

It was bipedal, meaning the species walked upright on two legs like us. But long arms and relatively short legs suggest it still had some capacity for cautious tree climbing like more ancient hominins.

How big was Homo habilis’ brain?

Homo habilis’ brain size is of interest, as a large brain in relation to body size is a human characteristic. It’s also thought to be indicative of mental abilities.

Fred led research published in 2015 that digitally reconstructed the braincase of skull bones found at Olduvai Gorge. The fossils included a broken lower jawbone.

‘We showed that the jaw was very primitive, but the brain was actually larger than expected,’ says Fred. The reconstruction suggests that Homo habilis’ brain could be up to 800cm3 in size - much larger than any australopith and similar to early Homo erectus.

Except for one specimen called KNM-ER 1805, which had a small one, Homo habilis fossils don’t have the sagittal crest that more ancient hominins tend to have. This bony ridge on the top of the skull results from powerful chewing muscles being attached to a relatively small skull. Its absence suggests Homo habilis didn’t habitually eat tough food.

Side view of a Homo habilis skull (KNM-ER 1813) found at Koobi Fora, Kenya. This species had a cranial capacity ranging from about 500 to 800cm3 - a brain size ranging from that of Australopithecus to early Homo erectus.

What tools did Homo habilis use?

Homo habilis used simple stone tools made from chipped pebbles and flakes of stone. They’re often called Oldowan tools because the first such artefacts came from Olduvai Gorge. Some scientists prefer the term Mode 1 tools.

This type of tool was in use from about 3.0 million to 1.3 million years ago during the early Stone Age, known scientifically as the Lower Palaeolithic.

Though simple, Oldowan stone tools marked a significant shift in the technology available to early humans, enabling them to do new things such as butcher large animals.

A collection of Oldowan tools found at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. They date back to about 1.8 million years ago.

Was Homo habilis really the ‘handy man’?

Homo habilis certainly did use stone tools. However, experts have now dated the oldest known stone tools to 3.3 million years ago. This is far older not only than the oldest evidence of Homo habilis but the entire Homo genus. So it’s no longer clear that Homo habilis or even other early humans were the first users of stone tools.

This is supported by a discovery at Nyayanga, a site on the shore of Lake Victoria in Kenya, reported in 2023. Scientists unearthed the remains of the early human relative Paranthropus alongside early stone tools. The artefacts are thought to be up to three million years old - the oldest known example of Oldowan technology anywhere in the world.

This discovery also reignites the possibility that the Nutcracker Man, Paranthropus bosei, was the original maker of the tools attributed to Homo habilis at Oldupai Gorge.

Cranium casts of Paranthropus boisei OH5 (left) and Homo habilis OH24 (right), which were both discovered at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, alongside stone tools. We still can’t be sure who was the first stone tool user.

What did Homo habilis eat?

Evidence suggests Homo habilis had quite a varied diet and ate fruit, leaves, woody plants and some meat. They didn’t make a habit of eating very tough foods such as nuts, hard tubers or dried meat. The thick enamel of their teeth meant they could if they had to though - possibly when their preferred foods weren’t available.

Examples of large animal bones bearing butchery marks suggests Homo habilis was using tools to prepare meat. But since several species lived at the same time, it’s hard to say definitively that Homo habilis made the marks. Chemical analysis proves their diet did include meat though.

Did Homo habilis hunt?

Homo habilis were probably scavengers rather than hunters.

As their grassland environment got cooler and drier, this may have driven them to start scavenging for food. Sharp tools would have been a great help for picking meat from carcasses left behind by predatory animals.

A hammerstone tool discovered at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, dating to between 1.85 million and 1.6 million years ago. This hard pebble would’ve been used to knock flakes off other stones to create sharp edges.

How did Homo habilis live?

Compared with more modern species like Neanderthals, the fossil record provides little information about the culture and behaviour of Homo habilis and other early human species.

It’s only in the past one million years - long after Homo habilis went extinct - that we get strong evidence of people using fire in a controlled way. Evidence of hunting and building shelters is even more recent.

This leaves many questions still to be answered around how Homo habilis lived and behaved as a group.

Could Homo habilis speak?

It’s possible Homo habilis were able to use at least simple speech to communicate key information to one another.

Fred adds, ‘From Homo habilis’ behaviour of making relatively complex stone tools and knowing what we know about communication in great apes, I’m sure they had a complex way of communicating with each other.’

‘This likely included a form of language - probably to say very basic things like, “What’s a good place to get raw material for stone tools?” or “I saw a hippo carcass over there”.’

Replicas of some of the OH7 Homo habilis fossils known as Johnny’s Child, from Spain’s Institute of Evolution in Africa, photographed when they were on temporary display. The original fossils were found by Jonathan and Mary Leakey on 4 November 1960 at Olduvai George, Tanzania. Image © Nachosan via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Important Homo habilis fossils

- Jonny’s Child (OH 7)

A 1.8-million-year-old partial skeleton of a boy with a much larger brain than the average australopithecine. This is the type specimen, or official specimen, for the species Homo habilis. It consists of part of a lower jawbone and teeth, an isolated molar tooth, two parietal bones - which form the sides and top of the skull - and 21 finger, hand and wrist bones. Jonathan Leakey and his mother, Mary, discovered the fossils at Olduvai Gorge in 1960.

- OH 62 (partial skeleton)

A 1.8-million-year-old specimen discovered in Tanzania in 1986 by Tim White. The skeleton’s relatively long arms and short legs revealed that the species’ proportions were more ape-like than previously thought.

- KNM-ER 1813 (cranium)

Some very significant fossils have been discovered in Koobi Fora in Kenya’s Lake Turkana basin. These include KNM-ER 1813 - a 1.9-million-year-old skull with a cranial capacity, or brain size, of 510cm3, which is not much larger than the average australopithecine brain. It was found by Kamoya Kimeu in 1973.

Cast of a reconstructed cranium from Olduvai Gorge. The original fossil - OH24, nicknamed Twiggy - was crushed flat.

Homo habilis vs Homo rudolfensis

Some fossils discovered at Lake Turkana typically had a flat and less protruding face than those attributed to Homo habilis.

These finds, such as the skull KNM-ER 1470, are now generally referred to as belonging to the species Homo rudolfensis. But some human evolution experts believe that such differences merely reflect natural variation within one species.

Siblings or strangers? Replicas of two crania from East Turkana, Kenya, believed to be Homo rudolfensis (KNM-ER 1470, left) and Homo habilis (KNM-ER 1813, right).

What came before Homo habilis?

We don’t know for sure what species Homo habilis evolved from, but new discoveries are being made all the time that provide new pieces to the complex puzzle of early human evolution.

A partial lower jaw attributed to an unknown Homo species and dated to 2.8 million years ago was recently discovered in Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia. This fossil could represent a possible link between Australopithecus and later species like Homo habilis, but this is by no means certain.

Is Homo habilis a direct ancestor of modern humans?

When Homo habilis was first discovered, palaeoanthropologists hoped that it would provide a link between primitive hominins like Australopithecus and our direct ancestor Homo erectus. Yet around two million years ago, Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, early Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei all shared the East African landscape.

Homo habilis and Homo erectus might have co-existed in East Africa for almost half a million years. This makes it hard to argue that Homo habilis is Homo erectus’ ancestor.

‘There’s this deep desire to find a shared ancestor from chimpanzees to modern humans in one long cascade,’ says Fred.

‘Of course there’s an evolutionary link between us and our earliest ancestors. Normally we think about these species as being the missing link in one single linear chain. But we should think of the link between us and our early human relatives as being between the lower branches of a big tree and a twig at the top.’

What makes us human?

Discoveries like Homo habilis and contemporary species challenge what we consider as uniquely ‘human’ attributes or behaviours - whether that’s brain size or the use of stone tools.

‘Homo habilis challenges the exclusivity that we constantly want to claim for ourselves - for Homo sapiens or the Homo genus,’ says Fred. ‘In contrast to our previous understanding, this species turns out to be much more primitive in its face and jaws than we thought. It is not the first tool maker either, as we have since unearthed tools made by 3.3-million-year-old early hominins around Lake Turkana.’ That is older than any known member of the Homo genus.

This article includes information from Our Human Story by Dr Louise Humphrey and Professor Chris Stringer.

Explore human evolution

Museum science is helping to answer where, when and how humans evolved.

Meet your ancient relatives

Embark on a seven-million-year journey of evolution and see fossil and artefact discoveries in our Human Evolution Gallery.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media