Earth is full of places that we see as uninhabitable, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents and hypersaline lakes to freezing poles and dry deserts.

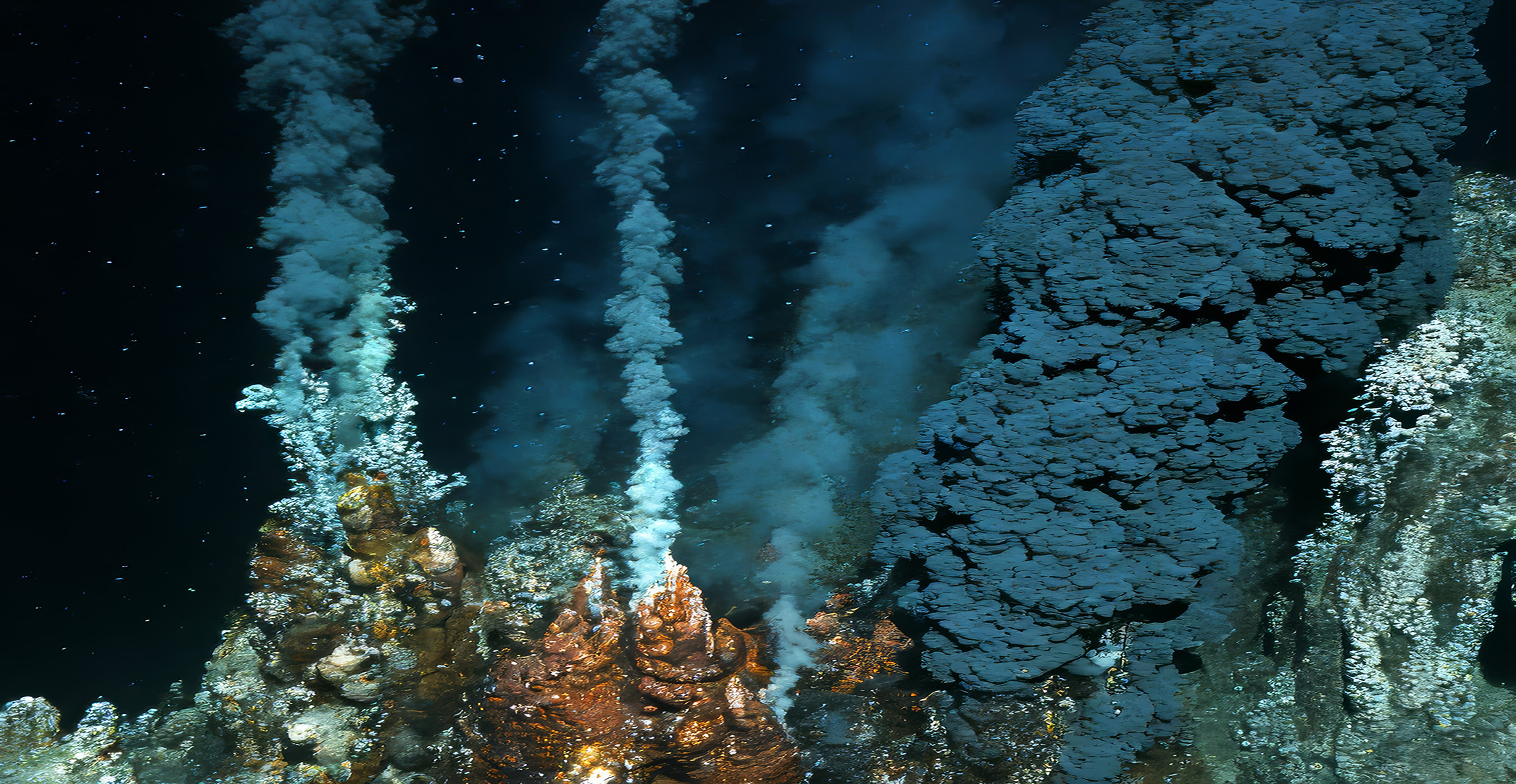

The temperature of the fluid released from deep-sea hydrothermal vents can reach over 400°C. © Gallwis/Shutterstock

While it may seem impossible for anything to live in such extreme environments, they’re actually home to an array of lifeforms that have found clever ways to survive and thrive.

Meet some of the creatures teaching us about the limits of life and the potential for finding it in other unexpected places.

Tardigrades

Small but mighty. Tardigrades live all over the world and can survive with barely any water. © William Edge/Shutterstock

There are more than 1,000 species of tardigrades. These eight-legged, microscopic creatures, often nicknamed water bears or moss piglets, are incredibly versatile and capable of surviving in some of the most extreme conditions. They live in deep oceans, rainforests, deserts and the Antarctic but also right under our noses in parks and gardens.

Tardigrades can survive long periods without any water by entering a death-like, dormant state called ‘tun’. In this state they dry up, collapse into a ball and drastically slow down their metabolism. They can stay this way for years until water becomes available again. In their normal active state, tardigrades only live for a few weeks.

In tun form, tardigrades are resistant to extremes that are typically thought of as being restrictive to life. They can survive freezing and near-boiling temperatures, being exposed to high levels of radiation and can go weeks without oxygen.

Scientists have run numerous experiments on tardigrades. They’ve even sent them into space, exposing them to direct solar radiation and the vacuum. They’re the only animal known to survive such conditions

“There’s always a question about what life could survive in space, especially multicellular life,” says our Principal Researcher, Dr Anne Jungblut. “Performing these tests help people understand what type of life can survive space conditions and what cellular molecules and genes provide protection. From this, we could potentially learn more about what would help with space travel of astronauts in the future.”

Deep-sea anglerfish

Deep-sea anglerfish are well-suited to their life in the depths of the ocean. © Kan Sukarakan/Shutterstock

Deep-sea anglerfish are found in every ocean. In the earliest stages of their lives, baby deep-sea anglerfish live in the plankton near the surface of the water. As they develop and grow, they descend into the depths, often to more than a kilometre below the surface.

“They’re a great example of the adaptations needed for living in the vast and extreme environment of the deep sea,” explains James Maclaine, our Senior Curator of Fish. “There are two problems that they have interesting solutions for – finding food and finding a mate.”

Female deep-sea anglerfishes have a dorsal fin ray that protrudes above their mouth like a fishing pole. This ray, known as the illicium, is tipped with a luminous organ that lures in prey close enough to be snatched. They also have large teeth and elasticated stomachs that allow them to swallow very big prey, making anglerfishes effective hunters.

The males don’t have a glowing lure or big teeth, but they do have huge nostrils. This helps them to sniff out a mate in the deep, dark ocean.

Female deep-sea anglerfishes are significantly larger than the males. “You see this a lot in fish living in an environment where there are limited food resources. Females need to be a certain size to make and carry the eggs and so need more food,” James explains.

In a family of deep-sea anglerfish known as warty seadevils, the males are just a few centimetres long compared to females that can reach around one metre. “Male warty seadevils attach themselves to the females like little parasites, feeding off her blood supply, and after some time, they completely fuse with her and become permanently attached,” says James.

This is a very effective way of keeping a mate in this vast deep-sea environment. Females can sometimes end up with several males attached.

Sea snakes

Not all snakes that are found in water are sea snakes. They must spend most of their life at sea to be a true sea snake. © Efrus/Shutterstock

Snakes are found all over the world, in a variety of environments and habitats. They’re able to occupy a diverse range of ecosystems, making them one of the most versatile organisms.

“Snakes are incredibly adaptable in terms of where they live and what they eat, which makes them a fascinating group,” says Dr Jeff Streicher, our Senior Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles.

Some of the most adaptable types of snakes are sea snakes. Unlike other snakes that venture into water only occasionally, the 64 species of true sea snakes spend most of their lives in the ocean. They have specialised adaptations to survive under the harsh and sometimes extreme conditions of marine life.

“The most successful living reptile to colonise the sea has been the sea snake and they’ve adapted to an extreme lifestyle in an amazing way,” says Jeff.

One of the most notable adaptations are their tails, which are flattened like paddles and help them move efficiently through the water. Sea snakes’ belly scales are also vital. These help them to maintain a laterally compressed shape – meaning being flattened from side to side – which enhances their swimming ability.

But sea snakes aren’t just skilled swimmers, they’re also masters at holding their breath. Unlike fish, they don’t have gills to absorb oxygen from the water. Instead, they surface periodically to fill their lungs before diving again.

While at the surface, sea snakes also take the opportunity to drink fresh water – a behaviour that was only discovered around 15 years ago.

“When it rains in the ocean, because of the difference in densities, the freshwater forms a lens on top of the saltwater. The snakes swim up and they’ll drink the freshwater that’s on top,” says Jeff.

Pompeii worms

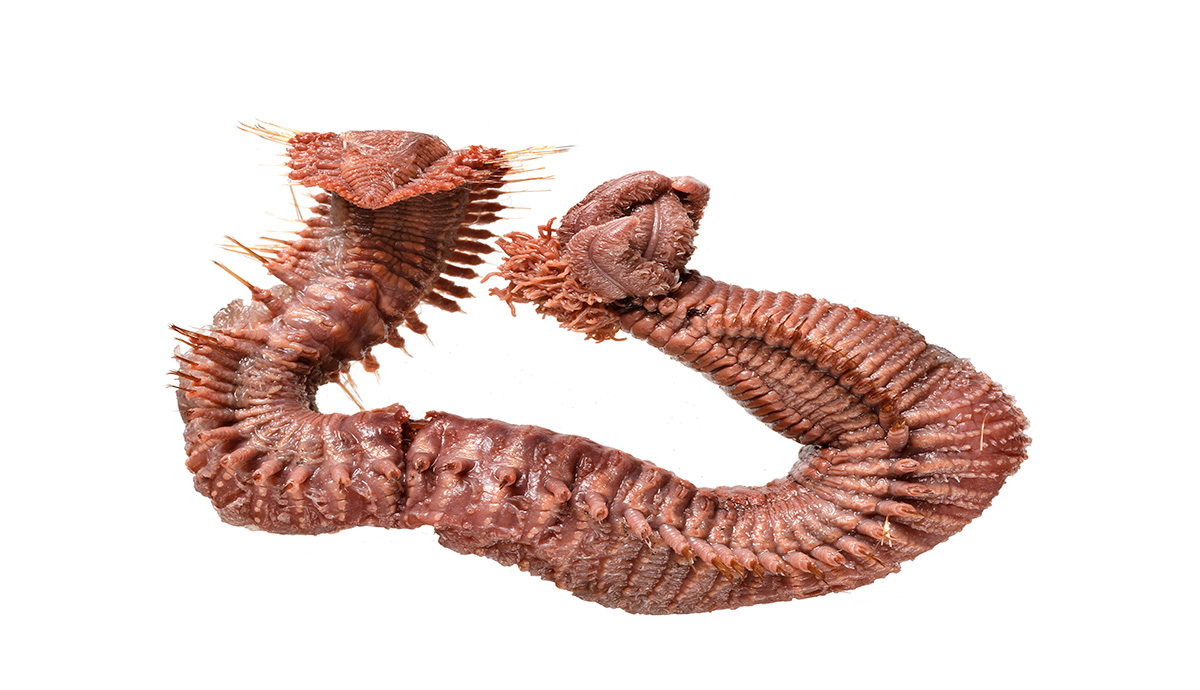

Pompeii worms, also known as Alvinella pompejana are an extremophile and live around deep-sea hydrothermal vents. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Pompeii worms are one of the most heat-tolerant animal species on Earth. They’re classed as extremophiles – organisms that can live in the most extreme conditions.

The worms live around hydrothermal vents in tubes on the ocean floor. These vents occur as the tectonic plates on the ocean floor move apart, expelling a fluid that has been heated to over 400°C. As it mixes with the colder seawater, it cools rapidly. Pompeii worms can survive temperatures of around 120°C, whereas most other animals can’t cope with anything over 40°C.

Pompeii worms reach up to 13 centimetres long and have a hairy fleece-like covering. This is a layer of bacteria that are thought to provide protective insulation from the heat.

The bacteria feed off a mucus excreted from small glands on the worm’s back. The worm can also use the bacteria as source food, meaning they have a symbiotic relationship.

Deinococcus radiodurans

Deinococcus radiodurans is a bacterium that is often referred to as one of the toughest known organisms. It’s renowned for its ability to withstand extreme environments, particularly high levels of radiation.

This organism can survive doses of ionizing radiation, such as gamma rays or X-rays that would kill most forms of life, including humans.

Ionizing radiation typically causes DNA damage. The key to this tough bacterium’s radiation resistance lies in its highly efficient DNA repair mechanism. This ability means it can rapidly recover from exposure.

Deinococcus radiodurans can also survive extreme dryness, both freezing and hot temperature extremes and chemical exposure.

“Extremophile microorganisms can help us to understand how life adapts, survives and grows under very extreme conditions. It helps us learn what the limits of life are and what chemical and physical conditions are required to make an environment habitable,” Anne explains.

Common thread snake

Although it may sound inconspicuous, the common thread snake has travelled all over the world via potted plants. © somyot pattana/Shutterstock

Its name might be unassuming, but the common thread snake is a prime example of clever adaptation to extreme environments.

These tiny, slender reptiles are sometimes referred to as worm snakes because they closely resemble earthworms. They’re among the smallest snakes in the world, with some species measuring only a few centimetres in length.

Thread snakes are burrowing snakes, spending most of their lives underground in soft, loose soils, under rocks or in decaying organic matter, such as leaves and rotting wood.

“They have to adapt to the environment, meaning they usually only come up to the surface if it rains a lot and they can’t breathe. They also have specialised skulls for eating ants and other burrowing insects, which is unusual for snakes.” says Jeff.

One type of thread snake has earned the nickname ‘flowerpot snake’, Jeff notes.

“They live in dark, soil-based environments which has resulted in an incredible dispersal around the world via us moving potted plants. They end up getting transported all over the world which means there are established populations everywhere,” Jeff explains.

Flowerpot snakes are parthenogenetic – meaning the females can reproduce without the need for males – allowing this species to establish themselves with relative ease. “They clone themselves. Unlike most vertebrate animals, it’s an all-female species making more of themselves,” says Jeff.

Icefish

Found in the freezing waters of the Southern Ocean and Antarctica, icefish have remarkable adaptations that allow them to thrive in some of the coldest environments on Earth.

Icefish are the only known vertebrates that don’t have haemoglobin – the protein responsible for transporting oxygen throughout the body and giving blood its red colour. Instead of red blood, icefish have transparent or white blood.

To survive the cold, icefish must preserve their energy. They have a very slow metabolism, meaning that they can store food and hunt less. When the time does come to hunt, they sit on the ocean floor and wait for prey to pass by.

Icefish have another crucial adaptation that enables them to survive in sub-zero waters – antifreeze proteins. These bind to tiny ice crystals, stopping ice from forming and keeping the icefish’s blood liquid, even in temperatures as low as -2°C.

Is Earth the only place with life?

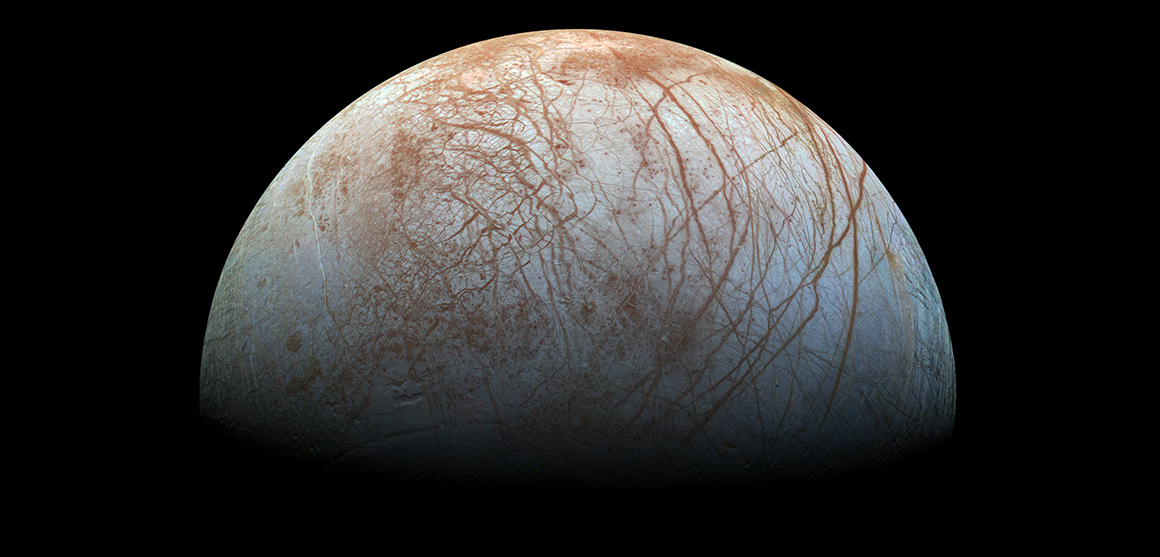

Life on Earth can exist under conditions that may seem almost impossible to survive. But what about in extreme environments on other planets or moons? Could they be home to life or are we alone in the universe?

Explore this big question at our new exhibition, Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth? Open now. Book your tickets.

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet before our exhibition’s mission ends.

Closes Sunday 22 February 2026

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media