Create a list of articles to read later. You will be able to access your list from any article in Discover.

You don't have any saved articles.

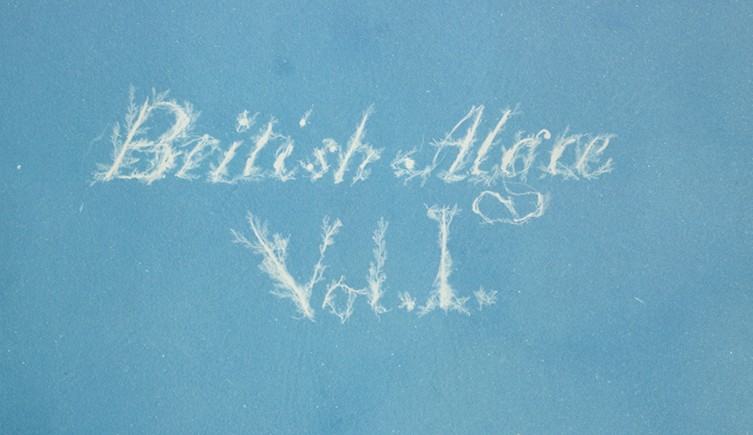

Cyanotype of British algae by Anna Atkins

English botanical artist, collector and photographer Anna Atkins was the first person to illustrate a book with photographic images.

Her nineteenth-century cyanotypes used light exposure and a simple chemical process to create impressively detailed blueprints of botanical specimens.

Anna's innovative use of new photographic technologies merged art and science, and exemplified the exceptional potential of photography in books.

Andrea Hart, Library Special Collections Manager at the Museum, says, 'With the introduction of photography, you get a whole new opening up of how natural history and science can be presented in print.

'Before Atkins's book on British algae and the photographic process, botanical images would have been restricted to the traditional printing processes of engraving or woodcuts, although the art of nature printing was also in its early stages around Atkins's time.'

Anna was born in Kent, southeast England, in 1799. She was raised by her father John George Children, who worked at the British Museum.

Photographic portrait of Anna Atkins

'She lost her mother very early in life and as a result formed a close bond with her father,' Andrea says. 'Her father was a well-respected scientist and the first president of the Royal Entomological Society of London, which in turn opened doors for Anna to participate in science that would not have been possible for many women at that time.'

Women were restricted from professionally practising science for most of the nineteenth century as it was an area dominated by men. Botany, however, was a subject that was accessible to all - in particular botanical art and illustration, which were considered a suitably genteel hobby for women.

Working at her father's side, Anna became an accomplished illustrator.

Prior to pursuing her botanical interests, in her early twenties she completed 256 scientifically accurate drawings of shells, which were published in her father's English translation of Jean Baptiste de Lamarck's catalogue titled Genera of Shells (1822-24). This volume of delicate watercolour and graphite illustrations is now held in the Museum's Library.

Original illustration of a giant clam by Anna Children for the English translation of Lamarck's Genera of Shells, c1820

In 1825 she married John Pelly Atkins and in the 1830s began to assemble her own collection of preserved plants.

Anna supplied specimens to renowned botanists at Kew Gardens. Her herbarium of British plants was donated to the British Museum in 1865.

Herbarium sheet showing seed plants specimens collected by Anna. In this case a single sheet is shared with her father John Children and close childhood friend Anna Dixon, a distant cousin to Jane Austen.

The couple were also closely acquainted with William Henry Fox Talbot, who invented the photographic process. Anna received a camera in 1841, though none of her works that used this apparatus have survived.

Instead, it was the cyanotype photographic process that would offer her the best photographic innovation to affordably document her specimens.

Not only did Anna's cyanotype impressions provide enough detail to distinguish one species from the next, they were also imaginative compositions.

'It just shows what a brilliant, creative and innovative mind Anna had to apply this brand new process to botanical specimens. But it's important to remember that she wasn't working in isolation.' Andrea says.

'She had access to a scientific education from an early age as well as having connections to and influences from other scientists and experts - but also attended meetings, including those at the Royal Society, where innovations around science and photography were being discussed.'

Before the invention of photography, scientists relied on detailed descriptions and artistic illustrations or engravings to record the form and colour of botanical specimens.

Anna's self-published her detailed and meticulous botanical images using the cyanotype photographic process in her 1843 book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. With a limited number of copies, it was the first book ever to be printed and illustrated by photography.

You can view images from the book held in the Library and Archive's Special Collections.

Two more volumes were produced between 1843 and 1853. In the volumes held at the Museum there are 411 plates each, with their scientific names handwritten by Anna.

There are thought to be only 20 known copies of Anna's book, 15 of which are substantially complete. She made every print herself.

The text pages and captions were photographic facsimiles of Anna's handwriting. In some cases, lettering appears to be formed by delicate strands of seaweed.

Anna's contribution to photography is commemorated by a blue Photographic Heritage plaque at Halsted Place School in Kent, where she lived until her death in 1871.

This blueprint process uses paper coated with a light-sensitive solution produced with ferric salts.

To make a print, a specimen is placed directly onto dry paper and exposed to light for between 10 and 40 minutes.

The image is fixed by washing in water, appearing as a white negative on a blue (cyan) coloured background.

The method for creating cyanotypes was developed by Sir John Herschel, who was also a family acquaintance.

Compared to the then-new field of photography, cyanotypes were a much lower-cost method for creating printed impressions.

Cyanotypes were also widely used by architects and engineers to create copies of plans - hence the term blueprint.