The dental record of a small, shrew-sized animal may have pushed back the origin of mammals by 20 million years.

The fossil remains show that mammals' forerunners were alive at the same time that the first dinosaurs were beginning to appear.

The evolution of early mammals may have been influenced by another major group of animals also on the rise in southern Brazil - the dinosaurs

The dental record of a small, shrew-sized animal may have pushed back the origin of mammals by 20 million years.

The fossil remains show that mammals' forerunners were alive at the same time that the first dinosaurs were beginning to appear.

A curious creature from Brazil is giving us a better understanding of the origin of modern mammals.

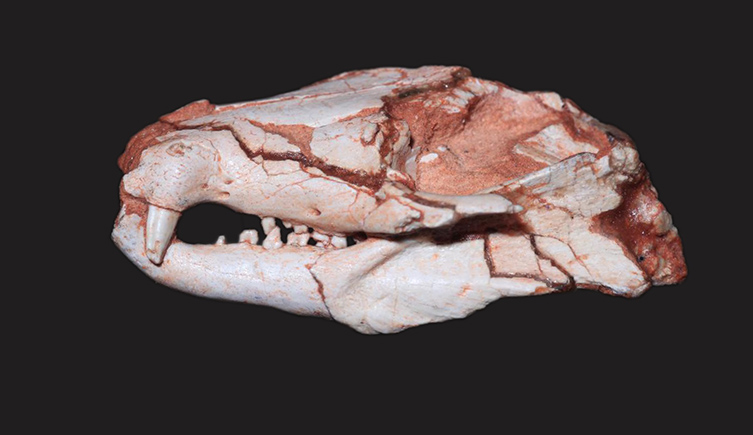

The fossils belong to a small, shrew-like animal called Brasilodon quadrangularis, and reveal that early animals with a mammal-like appearance were scampering around what is now Brazil some 225 million years ago. This makes it potentially the oldest-known mammal discovered to date.

It also shows that the tiny animal appeared right around the same moment that the earliest dinosaurs were also coming into existence.

This period in the history of life on Earth was defined by two massive extinction events, one that occurred right at the start of the Triassic and which killed off large swathes of life on Earth and a second at the end, which may have laid the ground for the eventual rise of the dinosaurs.

Dr Martha Richter, is a scientific associate at the Museum and senior author on the paper, says, 'Comparative studies with recent mammal dentitions and unique tooth replacement modes, together with the findings of genetic, developmental and physiological studies of reptiles and mammals suggest that Brasilodon could have been a placental, relatively short-lived animal, but there is no direct prove of that yet.'

'Dated at 225.42 million years old, Brasilodon is therefore the oldest known animal with a mammalian-like dentition in the fossil record contributing to our understanding of the ecological landscape of this geological period and the earliest stages of evolution of modern mammals.'

The new discovery is helping researchers build up a picture of the landscape and in which the first mammals and dinosaurs appeared in the aftermath of the extinction event at the start of the Triassic.

The worst ever extinction event took place some 252 million years ago, marking the end of the Permian Period.

While the causes of the extinction are not fully understood, the result of it was catastrophic. Known as the Great Dying, it wiped out some 90% of all life on Earth, killing off a huge range of different groups of marine species, insects, arthropods and vertebrates.

This created great change. While during the Permian the group of animals from which mammals branched out, known as the synapsids, were dominant, the wake of the Great Dying resulted in a shift in balance.

Despite the skull looking rather mammal-like, the teeth of Brasilodon initially led researchers to think it was a 'mammal-like reptile'

After around 10 million years in which the planet took to recover, the emerging terrestrial fauna of the Triassic Period was initially not so different from what came before. In what would eventually become southern South America, large herbivorous synapsids known as dicynodonts became dominant.

These animals were not true mammals though, in that they likely had some sort of a beak in lieu of teeth and walked with a sprawling, lizard-like gait. They were likely preyed upon by large predatory crocodile-like animals called thecodonds.

But scurrying around the feet of these relative giants was a much smaller animal.

Initially discovered in the 1980s and known from a large number of near-complete specimens, it would not be until 2003 that scientists realised Brasilodon was its own species. Reaching about 20 centimetres long, this shrew-sized animal had been something of an enigma.

While its body and skull looked fairly mammal-like, an initial look at its teeth eventually meant that it was classed as one of the extinct 'mammal-like reptiles'.

But by looking again as these fossils, and the chance to cross section some of the jaw bones, has led to scientists re-examining this assessment.

'The crucial, the most important question was what kind of dental replacement pattern occurred in this animal, because we know for sure two things,' explains Martha. 'Firstly, all reptiles are polyphyodonts, we know that because there isn't a single example in a fish, amphibian or reptile lineage that is not originally a polyphyodont animal.'

'And secondly, almost all known mammals are diphyodonts.'

To put it simply, all reptiles have a type of tooth replacement in which they can replace them multiple times, known as polyphyodonty. In mammals, however, the ability to replace teeth is limited to just two times, known as diphyodonty.

The results showed that the young Brasilodon specimens had a single tooth growing up, directly under already erupted teeth, proving that these animals were diphyodonts. As these fossils are some 20 million years older than any other definitive mammal, it suggests that the origin of this group goes back to at least 225 million years ago.

That is not to say this assessment is without controversy. Some suggest that Brasilodon is still a 'mammal-like reptile', and that instead these results show that diphyodonty can no longer be used to define mammals. Martha, however, is not convinced by this.

'From modern studies we know that diphyodonty is linked to a lot of mammalian traits,' says Martha. 'Diphyodonty has been extensively studied and it is not just about dental replacement, but a phenomenon that involves skull development and changes to the physiology, for instance, endothermy.'

'The whole skull undergoes transformations to allow for milk sucking.'

Many early dinosaurs such as Staurikosaurus have been found in the same rock formation as Brasilodon ©JohnnyMingau licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is what is known as a syndromic characteristic, in which one trait is linked to others. This would mean that something like diphyodonty, by its very nature, only ever exists in conjunction with other traits such as lactation, endothermy and fur that are mammalian characteristics.

'The only other possibility would be for diphyodonty to have evolved twice, but we don't have an example of that,' explains Martha. 'It is such a complex syndrome that it is unlikely that it has developed a second time.'

'The challenge is now out to re-examine the Triassic and Jurassic fossils of other species closely related to Brasilodon to assess how unique a phenomenon diphyodonty is.'

What is also of interest with Brasilodon are the other animals with which they were sharing the landscape. The region in which the fossils of this early mammal are found is dominated by large herbivore and crocodile-like reptiles.

'It is unlikely that the large carnivores would have been going after very small animals, but for the big herbivores instead,' explains Martha. 'So why did Brasilodon evolve to live in burrows? It is just a guess, but I think it was prey to another kind of predator that would go for them.'

This predator may have been one of the first dinosaurs, which by the end of the Triassic would evolve to become the dominant animals on land and stay that way for some 185 million years.

The fact that some of the first mammals and first dinosaurs have been found in the same place at the same time could just be coincidence. But, according to Martha, it could also be evidence of co-evolution, in which the presence and pressure from one species is driving the evolution of another and vice versa.

If this is true, then perhaps we owe our existence to ancient ancestors of Tyrannosaurus rex.

Find out what Museum scientists are revealing about how dinosaurs looked, lived and behaved.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media