A new paper challenges the traditional idea that our species evolved from a single population in one region of Africa.

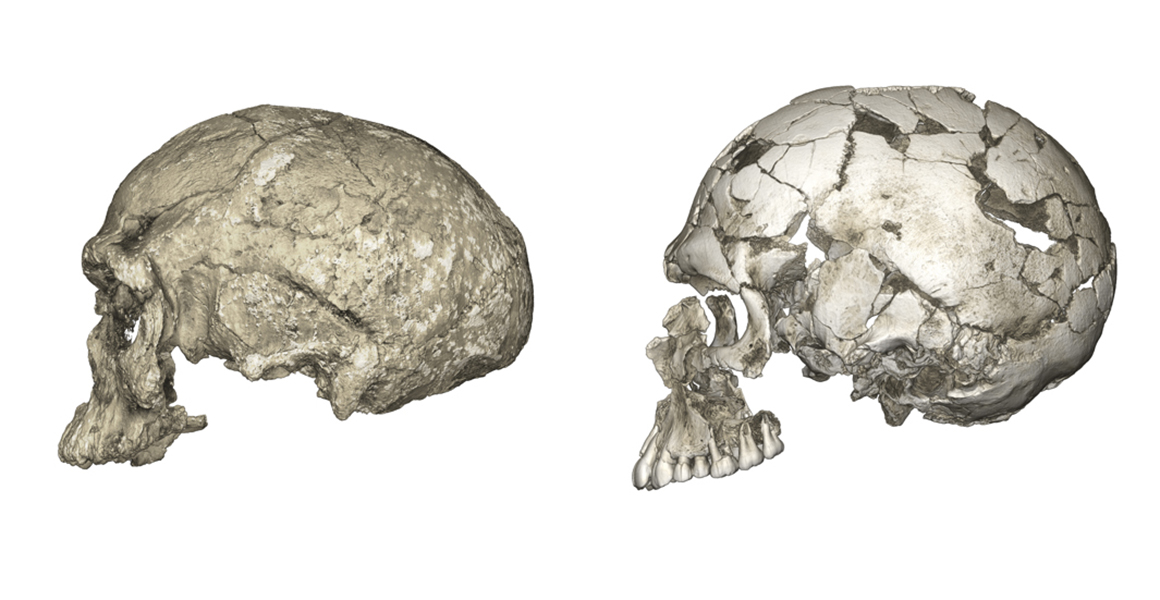

Images showing the evolutionary changes of braincase shape from an elongated to a globular shape. The latter evolves within the Homo sapiens lineage. Left: micro-CT scan of Jebel Irhoud 1 (~300 ka, Africa). Right: Qafzeh 9 (~95 ka, the Levant). Image: Philipp Gunz

Where did our species come from? It's a question we still don't have the answer to.

Scientists are sure that Homo sapiens first evolved in Africa, and we know that every person alive today can trace their genetic ancestry to there.

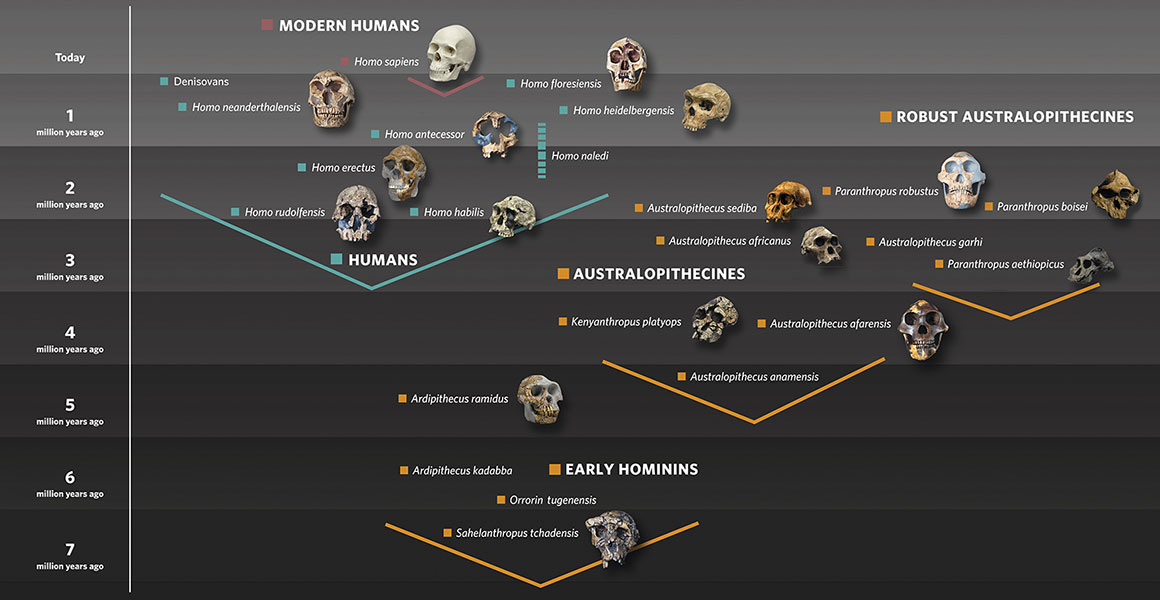

It has long been thought that we began in one single east or south African population, which eventually spread into Asia and Europe. But it seems that things were more complex than that - the link between those hominins and the humans on Earth today is neither straight nor simple.

A new paper, published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, suggests that there is plenty of evidence that H. sapiens actually emerged within the interactions of many different populations across Africa. Most of these were often isolated from each other, connecting only occasionally.

Eleanor Scerri, of the University of Oxford and the lead author of the paper, says, 'Fossil, archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the idea of Homo sapiens evolving in just one population in a single region is too simplistic.

'In this paper, a group of 23 scientists worked together to present a much more complicated view of the early history of our species.'

A new view

It was long thought that our species, H. sapiens, probably appeared in east Africa about 200,000 years ago. Alternatively, some archaeologists argued from cultural evidence that our species had originated in southern Africa.

But in 2002, Chris Stringer, a Museum expert and co-author of the new paper, argued that our African origins might be 'multiregional', with different regions of Africa playing a part at different times.

Key research that supported this view was published in 2017. Early H. sapiens fossils from Morocco were analysed and dated at 315,000 years old - far older than other fossils identified for our species.

The fossils were found alongside tools of the Middle Stone Age, a cultural phase normally associated with much younger fossils of H. sapiens.

It demonstrated that northwest Africa must also have been important in the early evolution of our species.

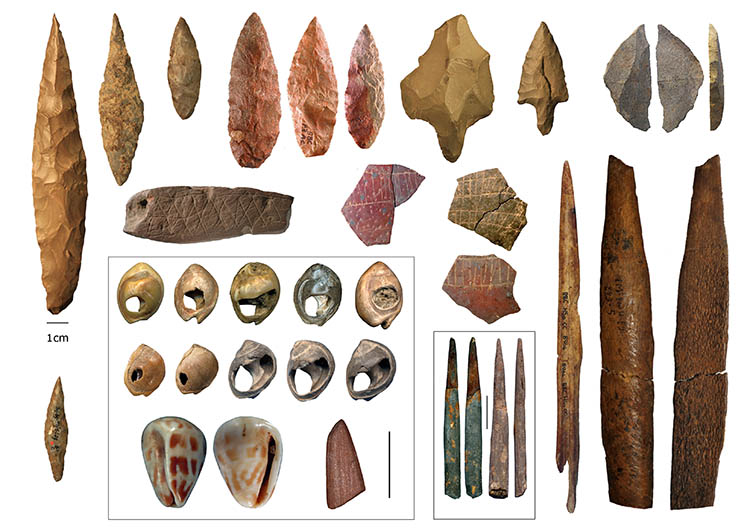

Middle Stone Age cultural artefacts from northern and southern Africa. Image: Eleanor Scerri/Francesco d’Errico/Christopher Henshilwood.

Scerri says, 'We now think that a huge range of H. sapiens lived all over the continent, from Morocco to South Africa. As well as this, they all looked different to each other, with a wide range of facial features and skull shapes.

'Ancient H. sapiens appear to have been even more physically diverse than the world's populations are today, which doesn’t fit with the idea that they all started from one small group.'

In this new view of African multiregionalism, some of these ancient humans may also have interbred with archaic hominins in Africa, separately from encounters with Neanderthals and Denisovans in Eurasia.

The evidence in our faces

We characterise modern humans as having small, slender faces, a protruding chin and a rounded skull.

These features start to emerge in scattered patterns in ancient Africa. The oldest known H. sapiens skulls have similar faces to modern humans, but their skulls are long, not round.

This suggests that our distinctive round skull and brain evolved within the H. sapiens species, not in those who came beforehand.

Some people have suggested that those fossils with different skull shapes might simply be an earlier, primitive species.

But Scerri, Stringer and their co-authors argue that the H. sapiens lineage goes back at least 500,000 years, and that it would have included more primitive fossils during its evolution.

Scerri says, 'All the features of the head that characterise contemporary humans do not appear until fairly recently, between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago.

'So instead of thinking that humans evolved in one clear line, perhaps semi-isolated populations of H. sapiens evolved alongside each other, at different rates. They were separated for thousands of years because they were so far apart, or because deserts and forests were in between them.

'H. sapiens likely descended from a set of interlinked groups of people, who were separated and connected at different times. Each one had different combinations of physical features, with their own mix of ancestral and modern traits.'

The Middle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age emerged in Africa more than 300,000 years ago. Ancient humans began to use prepared core technologies (hand tools made of rocks like flint that were pre-shaped by flaking off small pieces, before larger flakes were removed), marking a change in human culture. Evidence of more complex stone tools is found across Africa and dates to about the same time period.

Different populations of humans made a variety of different tools. For instance, in Central Africa, people made heavy axes, bifacial lanceolates, blades and picks. In the grasslands and savannah of north Africa, there were tanged implements.

Although humans in Africa entered the Middle Stone Age around the same time, they created different tools depending on where they lived. These differences suggest that human populations were isolated from each other for a long time, perhaps due to geographic features such as deserts and rivers.

This evidence from across the continent adds weight to the idea that modern humans evolved all over Africa, not just in one area.

Scerri says, 'It is remarkable that different types of evidence seem to support each other, all of which are crystallising into an exciting new view of our origins.'

More information

- Read the paper in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

Explore human evolution

Museum research and collections are helping to answer where, when and how humans evolved.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media