An early-modern human fossil from a cave in Israel has been dated to around 180,000 years ago, showing that Homo sapiens left Africa more than 40,000 years earlier than previously believed.

Museum human origins expert Prof Chris Stringer says the findings add further evidence to the complex picture of when modern humans dispersed across the globe.

'The find breaks the long-established 130,000-year-old limit on modern humans outside of Africa. I think the new dating hints that there could be even older Homo sapiens finds to come from the region of western Asia.'

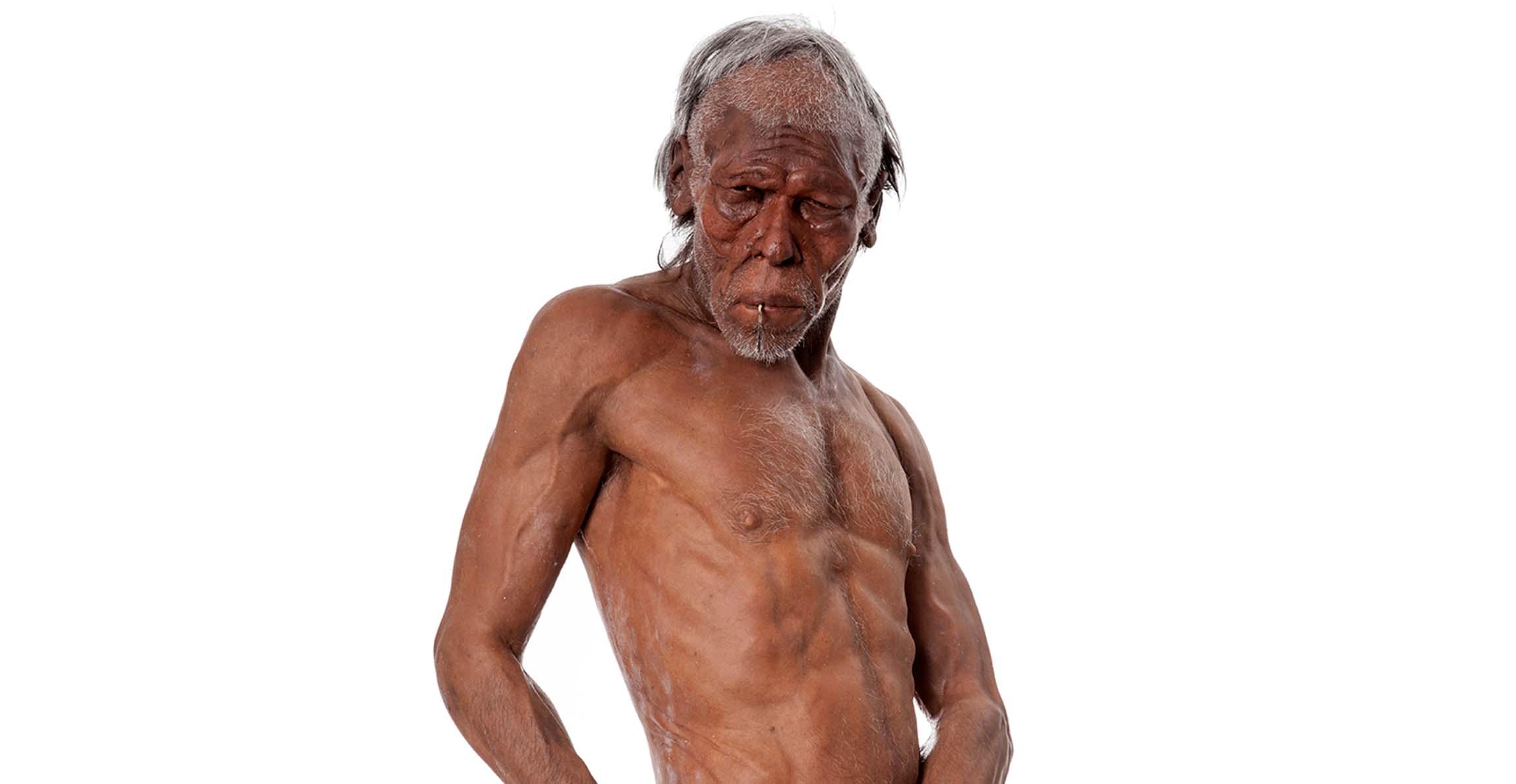

The fossil jaw fragment found in the cave, with features indicating it was from a Homo sapiens

An ancient jawbone

The research, led by a team from Tel Aviv University, excavated remains from Misliya Cave on Mount Carmel, northern Israel. The cave is part of a complex of prehistoric caves along the mountain, which show successive periods of occupation by early human species.

The team found part of a fossil human jaw with anatomical features that correspond to the modern human species Homo sapiens, as opposed to other pre-modern humans such as Neanderthals.

The researchers dated teeth from the jaw and flint tools found with the remains, obtaining an average age for the specimens of about 177,000-194,000 years old.

Until now, the earliest fossil evidence for Homo sapiens outside Africa was from other sites in Israel, dating up to 130,000 years ago.

Out of Africa, again

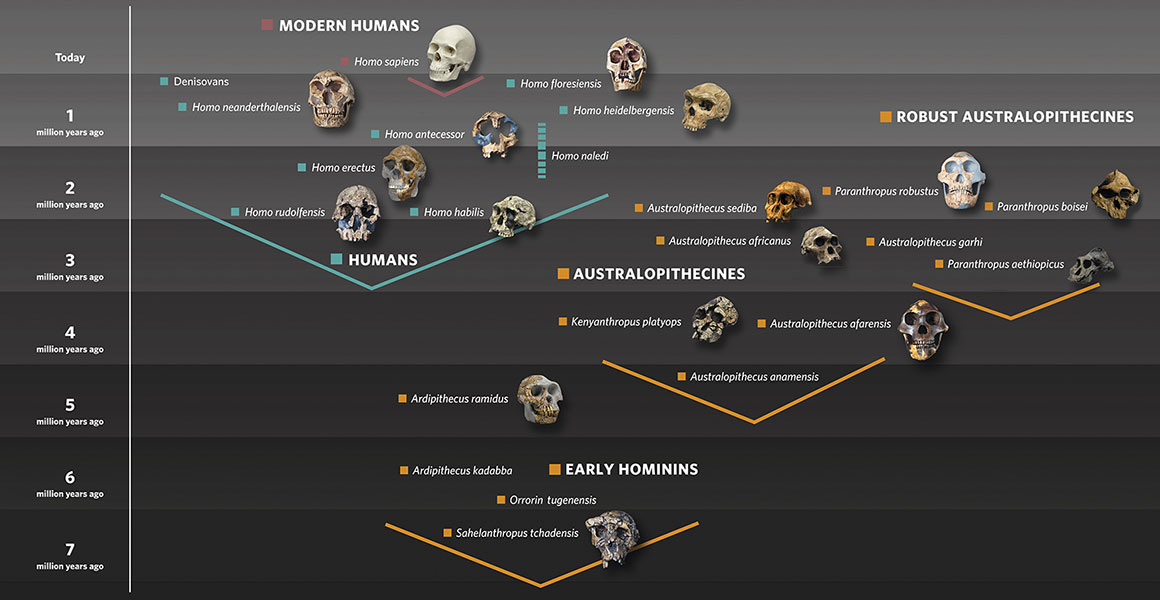

Homo sapiens evolved in Africa before expanding to spread around the globe. Genetic data indicate that the ancestors of current human populations outside Africa did not leave that continent until about 60,000 years ago.

This new discovery adds to the picture that various Homo sapiens migration waves left Africa earlier than this, but were largely unsuccessful compared to the wave around 60,000 years ago. Their lines of descent must have eventually died out or were overprinted by later waves, as they have contributed little or nothing to our current genetic make-up.

The Misliya cave excavation area where the jawbone was found

A precarious haven

In a comment piece for the journal Science on the new research, Stringer and Julia Galway-Witham - both scientists at the Museum - observe that there were several humid phases between 244,000 and 190,000 years ago in western Asia, one or more of which could have facilitated the spread of Homo sapiens into the region.

But Stringer and Galway-Witham add that the region may have proved a difficult area to thrive in long term:'There were severe periods of aridity before and after this time, meaning that the region was probably more often a "boulevard of broken dreams" than a stable haven for early humans.'

A potential melting pot

While the Homo sapiens pioneers into western Asia may have ultimately proved unsuccessful, they could have left more than fossils and tools behind.

There are traces of Homo sapiens genes being introduced into Neanderthals at least 220,000 years ago, so the two species must have interacted and bred together at some earlier point.

This region may have been a place where the species met, speculates Stringer:

'As the modern human and Neanderthal lineages evolved during the last 500,000 years or so, they could regularly have expanded into the Levant and Arabia in the good times, then becoming extinct in the bad times.

'Thus this area was not only a potential migration route between Africa and Eurasia, in either direction, but it could also have been a melting pot on numerous occasions.'

Related information

- Read the scientific papers in the journal Science on the new discovery

- Hear more from Museum scientists in a comment piece on the research in the journal Science

- News about the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils discovered in Morocco

Human Evolution

Explore more about where we come from and what makes us human.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media