What most of us would recognise as a jellyfish - the otherworldly, gelatinous aquatic animals renowned for their sting-filled tentacles - is actually just the final stage of these animals' life cycle.

At least, it usually is.

What most of us would recognise as a jellyfish - the otherworldly, gelatinous aquatic animals renowned for their sting-filled tentacles - is actually just the final stage of these animals' life cycle.

At least, it usually is.

Not all jellyfish play by the same rules, and one species may have discovered the secret to immortality.

The life cycle of most jellyfish species is similar. Museum curator Miranda Lowe explains, 'They have eggs and sperm and these get released to be fertilised, and then from that you get a free-swimming larval form.

'The larva will move about in the current until it finds a hard surface to establish itself. It will then start to mature and grow. Larvae mature into polyps, which will then bud off and mature into young jellyfish.'

An adult jellyfish is known as a medusa. Jellyfish belong to a group called Cnidaria, which also includes sea anemones and corals. As animals, they are subject to the cycle of life and death - though one species is known to bend the rules.

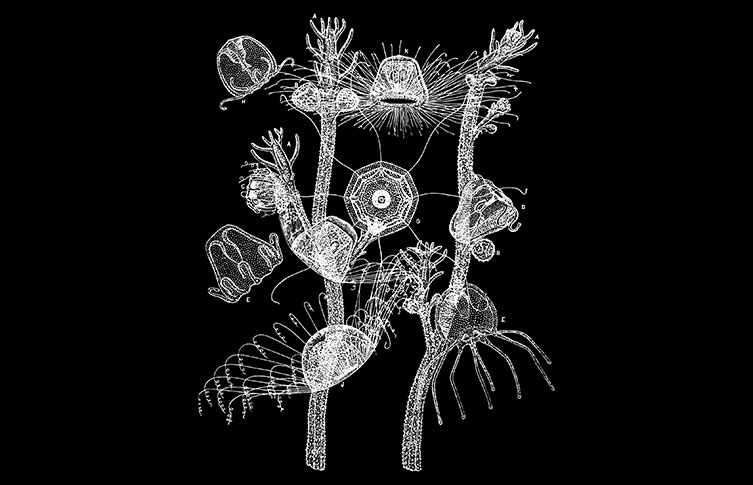

This illustration shows the different life stages of Turritopsis jellyfish. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The hydrozoan Turritopsis dohrnii, an animal about 4.5 millimetres wide and tall (likely making it smaller than the nail on your little finger), can actually reverse its life cycle. It has been dubbed the immortal jellyfish.

When the medusa of this species is physically damaged or experiences stresses such as starvation, instead of dying it shrinks in on itself, reabsorbing its tentacles and losing the ability to swim. It then settles on the seafloor as a blob-like cyst.

Over the next 24-36 hours, this blob develops into a new polyp - the jellyfish's previous life stage - and after maturing, medusae bud off. This phenomenon has been likened to that of a butterfly which, instead of dying, would be able to transform back into a caterpillar and then metamorphose into an adult butterfly once again.

The process behind the jellyfish's remarkable transformation is called transdifferentiation and is extremely rare.

Medusa cells and polyp cells are different - some cells and organs only occur in the polyp, others only in the adult jellyfish. Transdifferentiation reprogrammes the medusa's specialised cells to become specialised polyp cells, allowing the jellyfish to regrow themselves in an entirely different body plan to the free-swimming jellyfish they had recently been. They can then mature again from there as normal, producing new, genetically identical medusae.

This life cycle reversal can be repeated, and in perfect conditions, it may be that these jellyfish would never die of old age.

'We might be distracted watching much larger jellyfish, but the tiny things such as this can inform so much of our science about these animals,' says Miranda.

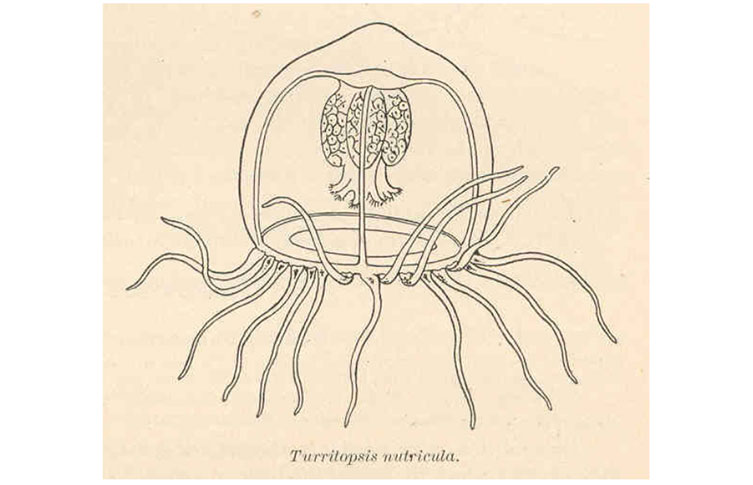

Turritopsis is a genus of tiny, translucent jellyfish. Image via The Freshwater and Marine Image Bank

The species T. dohrnii was first described by scientists in 1883. It was 100 years later, in the 1980s, that their immortality was accidentally discovered.

Students Christian Sommer and Giorgio Bavestrello collected Turritopsis polyps, which they kept and monitored until medusae were released. It was thought that these jellyfish would have to mature before spawning and producing larvae, but when the jar was next checked, they were surprised to find many newly settled polyps.

They continued to observe the jellyfish and found that, when stressed, the medusae would fall to the bottom of the jar and transform into polyps without fertilisation or the typical larval stage occurring. The discovery, aided by the spectacular nickname 'immortal jellyfish', captured the world's attention.

T. dohrnii may bend the rules to rejuvenate itself, but it can't always cheat death. For example, jellyfish, including immortal ones, are prey to other animals, such as fish and turtles. Polyps are also practically defenceless to predation by animals such as sea slugs and crustaceans.

Understanding how long jellyfish including T. dohrnii, can live for can be tricky.

Miranda explains, 'A lot of deep-ocean science takes a long time, and it is very costly to do observations over time to see change. The jellyfish also must have perfect conditions where they aren't going to be harmed by anything external, such as by humans or other predators.'

This is Turritopsis rubra, a jellyfish that is very closely related to T. dohrnii. It is currently unclear whether this species can transform back into a polyp. © Tony Wills via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

T. dohrnii is sensitive, making it also difficult to rear in a lab for studies. But despite the challenges, one scientist is known to have had long-term success with captive immortal jellyfish.

Japanese scientist Shin Kubota has kept populations of immortal jellyfish looping through their unusual back and forth life cycle since the 1990s. His work with the species is time-consuming, with Kubota needing to monitor and care for the colonies daily, even having to slice up their miniature meals of brine shrimp eggs under a microscope so they're small enough for the tiny jellyfish to eat.

But through his endeavours, Kubota has reported that over a two-year period, captive colonies of the jellyfish naturally rejuvenated themselves up to 10 times, sometimes at intervals of just one month.

Immortal jellyfish are thought to have originated in the Mediterranean Sea, however they are now found in oceans all around the world. It is thought this recently noticed invasion may have been predominantly caused by humans.

A prevailing theory is that ships are responsible for widely dispersing the creatures through Earth's oceans. The jellyfish's immortality makes it an excellent hitchhiker, after all.

Ballast water is pumped in and out of vessels like cargo and cruise ships to maintain stability. It is highly possible that immortal jellyfish get drawn in with this water and are able to survive ocean crossings thanks to their ability to reverse their life cycle when they experience stresses, such as a lack of food.

Zebra mussels in North America cause millions of dollars of damage each year. Image by D. Jude, University of Michigan via Wikimedia Commons

The immortal jellyfish is also relatively inconspicuous, which may have contributed to its spread being difficult to spot. It is tiny and translucent, and can have different features depending on where in the world it's living. From a study of T. dohrnii around the world, researchers found that immortal jellyfish in tropical regions like Panama had only eight tentacles, whereas those in more temperate waters, such as in the Mediterranean and Japan, can have 24 or more. It is not clear yet why they differ.

Another reason the immortal jellyfish's spread around the globe may have gone unnoticed for so long is that they don't have a perceivable negative impact. Invasive species can be problematic, and some, such as zebra mussels in North America, wreak havoc that costs enormous sums of money to fix. Others, like the hippos introduced to Colombia about 30 years ago, pose threats to the native wildlife they coexist with.

While there have not yet been any major problems identified that are linked to immortal jellyfish, their silent spread at the hand of humans is yet another good reminder of our influence on the natural world, even when we don't notice the effect we're having.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Find out more about life underwater and read about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

But are you a deep-sea enthusiast? Explore the inky depths in our expert-led, online and on-demand courseDeep Sea, available now.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media