Axolotls are friendly-faced salamanders that stay in their ‘tadpole’ form forever.

While we prize them for their looks and amazing regeneration abilities, in their native Mexico, wild axolotls are Critically Endangered.

Axolotls are brown-grey in the wild, but are sometimes bred to be pink. Image © Robert Röhl via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Axolotls are friendly-faced salamanders that stay in their ‘tadpole’ form forever.

While we prize them for their looks and amazing regeneration abilities, in their native Mexico, wild axolotls are Critically Endangered.

Read on to find out more about these characterful creatures.

The axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum, is a type of salamander that doesn’t go through metamorphosis.

Salamanders are amphibians that, like frogs and newts, start off living in the water.

Salamanders usually go through a process called metamorphosis to become adults – like a tadpole transforming into a frog. They’ll then mostly live on land. During metamorphosis salamanders typically change in a number of ways to adapt to their new habitat. For example, they replace their water-breathing gills for air-breathing lungs and grow lids for their eyes.

But axolotls never make this transition. Instead, they keep their frilly external gills and other juvenile features and stay living in the water for their entire lifecycle.

This is called neoteny, or paedomorphism. Although axolotls look like the ‘tadpole’ form of most salamanders, they do become adults in the sense that they’re able to breed. They do go some way to developing lungs, but they’re also able to breathe through their skin.

Axolotls’ closest relatives are tiger salamanders, Ambystoma tigrinum. As a group, Ambystoma salamanders are known as mole salamanders for the land-dwelling adults’ habit of living underground.

Axolotls retain feathery gills and long, tadpole-like tails. © JanBeZiemi/ Shutterstock

According to Dr Jeff Streicher, our Senior Curator in Charge of Amphibians and Reptiles, axolotls may have evolved their unusual life cycle due to their environment and the resources available.

“Axolotls are part of a group of closely related salamanders that have a range of lifestyles. Some can remain in the water if conditions on land are bad or can leave if, for example, the lake they live in starts to dry up,” says Jeff.

Over time, if staying in the water was better for axolotl survival and they matured sexually before they went through metamorphosis, then it made sense to keep all their water-adapted features.

In experiments, axolotls have been forced through metamorphosis by adding iodine to their water. This induces the release of hormones that kick-off the process of developing land-based traits. But too much iodine can kill an axolotl, and even if they successfully metamorphose they don’t survive as well as natural paedomorphic axolotls, so it’s not recommended for axolotl owners.

The axolotl’s alternative common name of Mexican salamander gives the game away.

Axolotls are native to lakes and wetlands in southern Mexico City, particularly Lake Xochimilco and Lake Chalco. But both lakes have been drained to reduce flooding, with Lake Chaco almost completely disappearing. Axolotls are confined to the canals of these lakes, and possibly a third lake, Chapultepec.

There’s also a large captive population of axolotls. They’re often found in zoos, labs and kept as pets.

Wild axolotls are a mottled brown-grey colour, but they can also be albinos. These are missing brown pigments and look pinkish-white. This attractive colouration is desirable in the pet trade and has been selectively bred for.

An albino, or leucistic, axolotl bred in captivity. © axolotlowner/ Shutterstock

Axolotls are often the top predators in their native habitats. They eat whatever they can get their jaws on, including molluscs, worms, insect larvae, crustaceans and even some small fish.

Axolotls can live 10-15 years in the wild, reaching sexual maturity after about a year. They reach up to 30 centimetres long and weigh around 50-200 grams.

An axolotl eating mosquito larvae. © Lapis2380/ Shutterstock

This is a question scientists would really like to know the answer to!

Like many species of salamander, axolotls have the remarkable ability to regenerate parts of their bodies. This includes limbs, eyes and even parts of their brains. Research labs around the world are trying to understand this incredible trait, which is one reason there are so many captive axolotls.

The ability may relate to the axolotl’s refusal to go through metamorphosis. In most animals, including people, there are genes that are only active as we’re developing that direct the growth of organs and limbs. Once we reach adulthood, these genes are silenced. But for axolotls, it appears these genes may get activated again when there’s an injury.

Exactly which genes and how their activation causes regrowth is the subject of ongoing research. Scientists have identified some candidate genes and are zooming in on what proteins are being expressed at each stage of limb regrowth. For now, they’re a long way from helping us regenerate limbs, but this potential means axolotls are very valuable to research.

“It seems like there’s a clear end-state of development that the axolotl always wants to be in, so if anything in its body gets modified, it moves back towards that,” says Jeff.

“Given that we have many developmental genes in common with axolotls, it would be very useful to humans if we could figure out exactly how they regenerate complex body parts.”

An axolotl regrowing one of its front feet. © axolotlowner/ Shutterstock

Given their primary habitat is so diminished, it’s no surprise that axolotls are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as Critically Endangered. Their population is decreasing, with only 50-1,000 adults thought to be living in the wild. It was anticipated they might be extinct by 2020, but thankfully that hasn’t happened.

Axolotls need deep water to thrive and plants to lay their eggs on. They’re sensitive to changes in water quality and urbanisation around their native lakes has led to pollution and habitat loss. People using the water can disturb these amphibians and new fish species introduced to the waterways, such as tilapia and carp, compete with the axolotls for food. Fish eat axolotls’ young too.

Axolotls used to be taken from the wild for food and the pet trade, but all pets are now thought to be bred in captivity.

Axolotls are sometimes known as a conservation paradox since they’re almost extinct in the wild, but are widely distributed in pet shops and labs throughout the world. However, this captive population is often very inbred, meaning there isn’t much genetic diversity. It makes these axolotls vulnerable to catastrophe, such as disease.

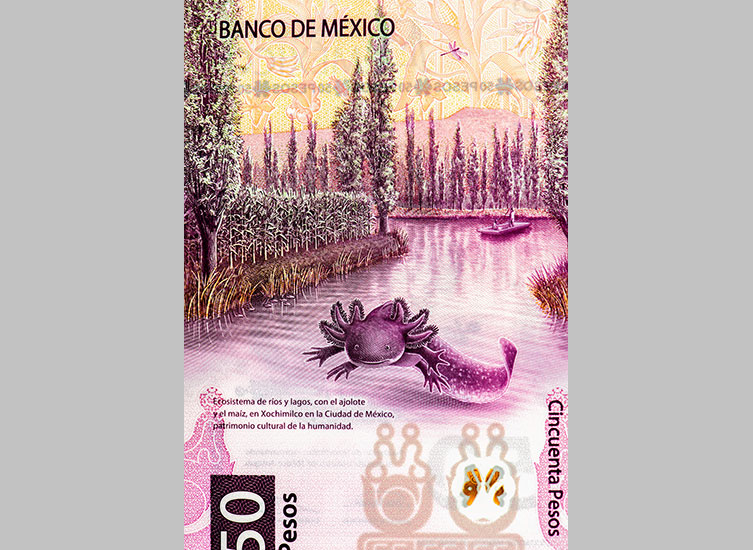

Axolotls are thought to be named after the Aztec god of fire and lightning, Xolotl, who transformed himself into one of these salamanders to avoid being sacrificed by fellow gods. The axolotl even features on the new 50 peso note, released in 2021 and awarded Banknote of the Year by the International Bank Note Society.

This animal’s deep roots in Mexican culture and status as a bit of an icon have been driving conservation efforts.

The 50 Mexican peso banknote, featuring the axolotl and its native habitat. © Prachaya Roekdeethaweesab/ Shutterstock

A species closely related to the axolotl, which can also keep juvenile characteristics, is the critically endangered Lake Pátzcuaro salamander, Ambystoma dumerilii. Local nuns have used it in a traditional cough medicine preparation for generations. Having raised the salamanders in captivity for 150 years, the nuns have teamed up with conservationists from Chester Zoo and researchers at the Michoacán University to see if their efforts can help re-stock the wild population, which is thought to number fewer than 100 adults.

As for the axolotl, the Mexican government and local conservation groups have several schemes to help them. Actions include restoring their freshwater habitat and encouraging traditional methods of farming that provide axolotl habitat.

In 2025, scientists successfully released 18 captive-bred axolotls into artificial wetlands near Mexico City. It gives some hope that, with the help of conservationists, there could be a positive future for wild axolotls.

Find out about environmental organisation MOJA’s conservation centre and their efforts to save this iconic species.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Learn from top experts with our on-demand courses, designed for all levels of interest in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media