Cold, dark and windswept - despite its calm appearance, the ice giant Uranus is a planet of extremes.

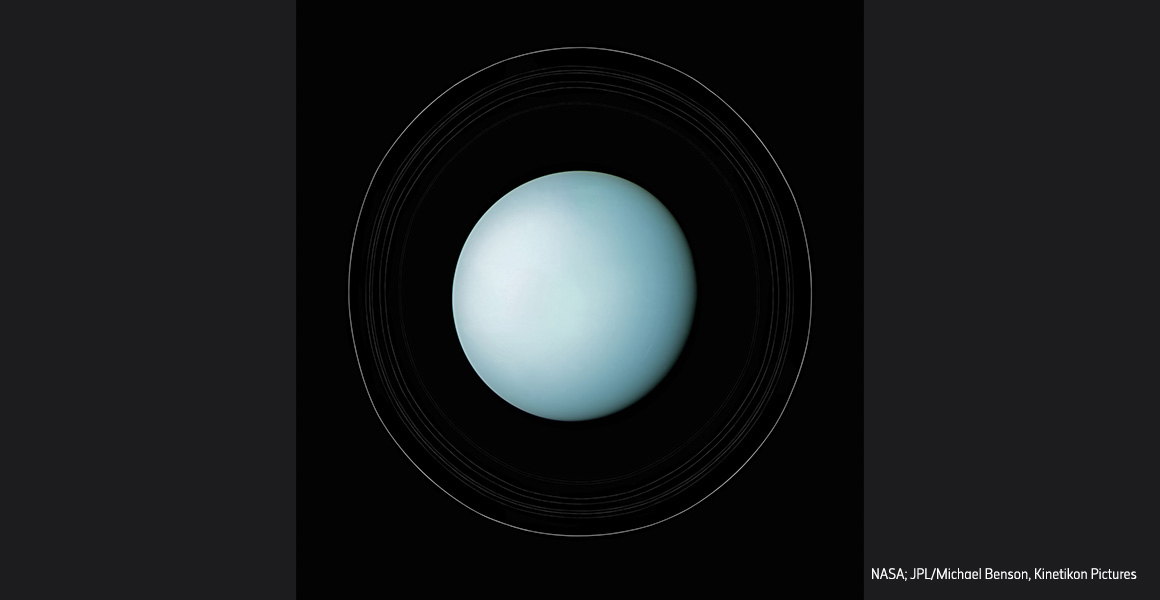

Uranus surrounded by its rings. © NASA; JPL/Michael Benson, Kinetikon Pictures

Orbiting the Sun at an average distance of 2.9 billion kilometres - more than 19 times further out than the Earth - Uranus was the first planet to be discovered with the aid of a telescope, in 1781. Previous planets, from Mercury to Saturn, had all been known since ancient times.

Later observations revealed the planet to be a strange, icy world. Its atmosphere is the coldest of any planet in our solar system, and contains clouds of methane, hydrogen sulphide and ammonia.

It is this methane that gives the planet its distinctive aquamarine colour, which is visible in this image of Uranus, one of 77 composite photographs that appeared in our 2016 exhibition, Otherworlds: Visions of our Solar System.

Toppled world

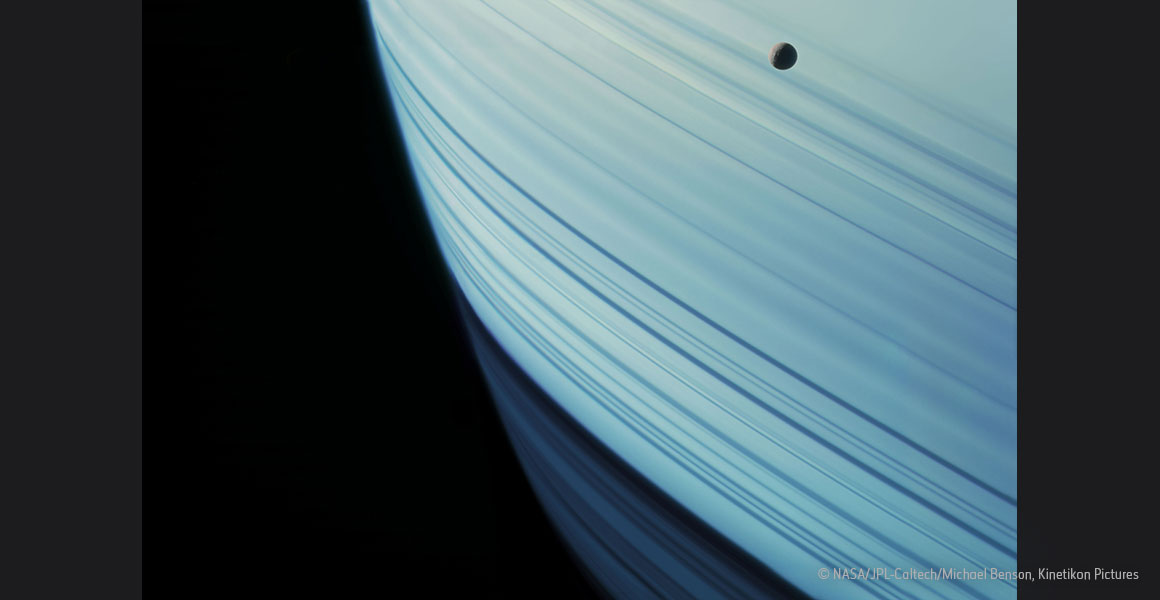

The image also shows the faint ring system that surrounds the planet. Discovered in 1977, the rings were only the second such system to be found after Saturn's.

However, unlike Saturn, Uranus and its rings are 'tilted' almost completely sideways, like a spinning top that has fallen over.

This means that as the planet orbits the Sun, each of its poles experiences continuous sunlight for around 42 years at a time, followed by 42 years of complete darkness.

Vast storms

This image is from 1986, showing the planet's southern hemisphere at the height of its decades-long summer.

Since then, as its seasons have changed, Uranus has experienced tremendous storms. Winds have been measured reaching over 800 kilometres per hour, accompanied by cloud systems stretching for up to 18,000 kilometres.

Clearly Uranus is not the calm and featureless planet it once appeared to be.

Explore space

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?

Snap a selfie with a piece of Mars, touch a fragment of the Moon and lay your hands on a meteorite older than our planet before our exhibition’s mission ends.

Closes Sunday 22 February 2026

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media