On a clear night, if you point a telescope at the sky, you might spot a line of bright, star-like lights. What you’re actually seeing is Jupiter and its four Galilean moons – Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa.

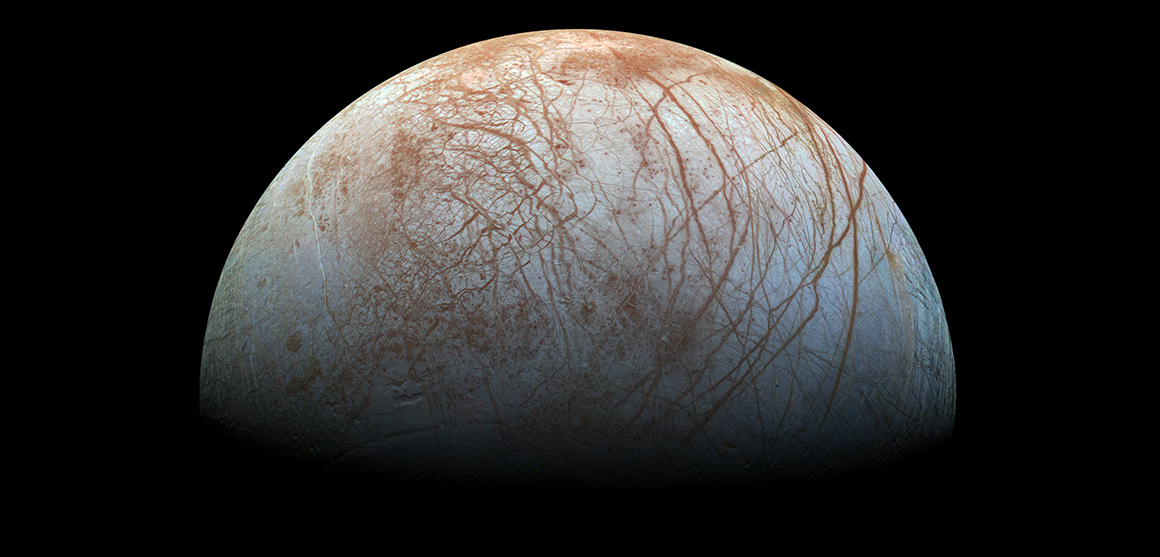

The lines on Europa’s surface are thought to be cracks in the ice that are caused by Jupiter’s gravitational pull. Image © NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute via ESA, public domain.

The Galilean moons are named after the astronomer Galileo Galilei, who observed and documented them in the seventeenth century. His observations of these moons were revolutionary, as they provided evidence that not everything in the sky revolved around Earth. This helped to shift scientific thinking toward a Sun-centred solar system.

Jupiter is the biggest planet in our solar system – if it was hollow, roughly 1,000 Earths would fit inside it. While we have one moon, scientists believe Jupiter is orbited by a whopping 95 moons. One of the largest of these is Europa – an icy mass that’s being closely investigated as a potential home for extraterrestrial life.

Our scientists Ines Collings and Nicole Sutherland are here to share more about this mysterious icy moon.

What is Europa?

Although Europa is the fourth largest of Jupiter’s 95 moons, it’s the smallest of the Galilean moons – the largest being Ganymede. With an equatorial diameter of about 3,100 kilometres, Europa is slightly smaller than our moon – about 90% its size.

After Io, Europa is the second closest moon to Jupiter. “Europa orbits Jupiter at about 671,000 kilometres from the planet, which itself orbits the Sun at a distance of roughly 780 million kilometres. This is more than five times further from the Sun than Earth is,” explains Nicole.

Europa is the smallest of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons. Image © NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, public domain.

Being so far away from the Sun, and only having a thin oxygen atmosphere, means temperatures and light on Europa are extremely low. Average surface temperatures range from −227 degrees Celsius at the poles to about −177 degrees Celsius at the equator. Even in the warmest conditions, temperatures only reach −143 degrees Celsius. These temperatures are so low that even gases such as carbon dioxide would freeze solid.

A day on Europa – which is measured by the time it takes it to complete one spin on its axis – lasts three and a half Earth days. Europa always keeps the same side facing Jupiter because it orbits on its own axis at the same rate that it orbits the planet. This is a phenomenon called tidal locking or synchronous rotation and it’s the same thing that we experience with our moon.

What is Europa made of?

Europa is incredibly smooth. Its surface is mostly covered in a crust of bright, reflective ice – the thickness of which is still being studied. The lack of impact craters suggests that Europa has a surface that’s geologically young and constantly being reshaped. This has led scientists to believe that there’s an ocean under the ice. Going deeper, it’s thought Europa has a central metal core, surrounded by a rocky mantle.

Ines explains, “even though Europa is comparable to the size of the Moon, it’s thought to host twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined. The chemical composition of the liquid ocean is still debated, since no direct sampling exists yet, but it’s thought to be enriched in a combination of ions.”

Europa’s surface is covered in a thick ice crust. Image © NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, public domain.

But how can liquid water exist so far from the Sun, where temperatures are unimaginably cold? The answer lies in heating from within.

“The reason for the higher temperatures of the ocean is due to radiogenic heating from the rocky mantle and tidal heating from gravitational interactions with Jupiter and the neighbouring moons,” explains Ines.

In other words, Europa is constantly being stretched and squeezed by Jupiter’s enormous gravity and by the gravitational pull of its sibling moons Io and Ganymede. This process generates heat inside Europa, preventing its ocean from freezing solid.

Could Europa support life?

Life as we know it needs three main ingredients – water, chemistry and energy. For life to develop, it also needs time to get started so there’s no point looking for life on newer planets.

Europa may have all the ingredients needed for life. Its ocean contains water, likely salts and minerals, energy from tidal flexing and possibly underwater hydrothermal vents. On Earth, such vents host thriving ecosystems of bacteria, tube worms, crabs and other organisms.

Plus, Europa is as old as Earth, meaning it’s had billions of years for life to potentially develop. If life exists there, it may be microscopic and adapted to life in a deep, dark ocean, just like some of Earth’s extremophiles – organisms that live in extreme conditions, such as high temperatures or high pH.

A 2026 study suggests that Europa’s seafloor may actually be calm and quiet. On Earth this would mean there wouldn’t be enough geological activity to provide the conditions needed for life as we know it to develop. But this isn’t to say that different kinds of life couldn’t exist on Europa – after all, it’s an alien world!

Are there missions to explore Europa?

There are a few missions that are taking place to learn more about Europa and the possibility of life there.

In 2024, NASA launched the Europa Clipper Mission – it’s the largest spacecraft NASA has ever used for a planetary mission. It will travel 2.9 billion kilometres and reach Jupiter by 2030. It will then conduct 49 flybys of Europa.

The main goal of the mission is to find out if there are places below Europa’s icy crust that can support life. The mission also hopes to find out more about the chemical composition of its surface and ocean.

Europa is bathed in radiation from Jupiter, so the spacecraft has vault walls made of titanium and aluminium to protect the instruments inside

Expected to arrive it 2031, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer will study Jupiter and three of its moons. Image © ESA/S. Corvaja, public domain.

Another mission taking place is the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, known as Juice. The European Space Agency launched Juice in 2023. It will study Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, as well as Jupiter itself. Its mission is to understand these moons’ oceans, surfaces and potential habitability, as well as to learn more about Jupiter’s complex environment.

While Juice and Europa Clipper will not land on Europa, their observations will shape future missions. One day, scientists hope to send a lander – and perhaps even a robotic probe that could melt through the ice to explore the ocean below.

So, the next time you look up at the night sky, think about Europa and the secrets lying beneath its surface.

Ready to explore the universe?

Expand your knowledge with our on-demand course Rocks in Space. Explore the wonders of asteroids, comets and more with our expert-led, online course.

Explore space

Discover more about the natural world beyond Earth’s stratosphere.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media