Humans aren't the only creatures that hoard, collect and decorate their homes. In fact, several animals exhibit these types of behaviours.

A male satin bowerbird organises the blue items he has collected. © Imogen Warren/ Shutterstock

Collecting behaviours occur in nature for a range of reasons, from seducing a mate to intense self-defence.

One of the first creatures that might come to mind when you think of animal collectors are magpies, with their reputation for stealing jewellery and trinkets. However, magpies are actually very shy and frightened of new (and shiny) things. Their secluded, thorny nests are practical and minimal, with no bling in sight.

While magpies are off the hook, there are a number of other curious animals for whom more is definitely more.

Lacewing larvae

A lacewing larva covered with debris including the remains of its prey. Image © RudiSteenkamp via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Lacewing larvae (also known as 'junk bugs') have been collecting trash for at least 110 million years, making them some of nature's oldest collectors.

Thousands of species of lacewings can be found flourishing in tropical and temperate climates around the world. Most varieties are predatory, eating aphids, moths, spiders, mites and many garden pests, which has them put to use in industry for pest control.

The larvae collect a mix of vegetation and the carcasses of other insects, which they selectively gather and display by impaling them on the spiny protrusions on their backs.

Quite different in appearance from their delicate-winged adult forms, lacewing larvae come to resemble walking trash balls.

Adult green lacewing, Chrysopa oculata. Image © Judy Gallagher via Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Why do lacewing larvae collect trash?

For lacewing larvae, collecting has a double function: it helps to make them less attractive to predators and less familiar to their quarry.

Larvae can be highly selective about what they collect, tailoring their disguise to their environment and desired prey.

Satin bowerbird

A male satin bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) stands inside his bower. © Rachel E Foster/ Shutterstock

Found on the east coast of Australia, the satin bowerbird has quite a discerning eye for blue objects. Solitary adult males travel far and wide to collect all manner of blue things with which to decorate their bower (consisting of two parallel walls of sticks) and woo potential mates.

Successful bowers can boast painstakingly curated collections of blue feathers from other birds, plus shells, flowers, butterflies, plastic straws, foil crisp packets, pegs and bottle caps.

Objects that reflect ultraviolet light are particularly treasured, and hot competition for these items often leads to a cycle of theft during the mating season. Enterprising builders will even grind up blue pigments with their beaks and paint their nests to achieve just the right look.

Why do bowerbirds collect blue things?

Satin bowerbirds favour the colour blue as a reflection of mature male birds' colouring. Females and juvenile males are olive-green and brown in colour, while mature males have a glossy, blue-black plumage and blue eyes. Males only begin to acquire their blue plumage in their fifth year and reach their full, dapper plumage at seven years old.

A high concentration of blue things in a well-furnished bower is a clear cue to prospective females that the builder is ready for mating. Bowers are maintained year-round, although peak bower attendance is in the pre-breeding period from August to October, when males will spend about 70% of daylight hours within 50 metres of the bower.

The bower becomes the site for ritual courtship during the breeding season which runs from October to February.

When a female arrives to inspect the bower, the male satin bowerbird will perform a display involving calls, strutting, bowing and quivering. He will also usually carry one of his blue trinkets in his bill. If the female approves, she will enter the screened avenue of sticks for mating and then fly away to nest and roost by herself.

Bone-house wasp

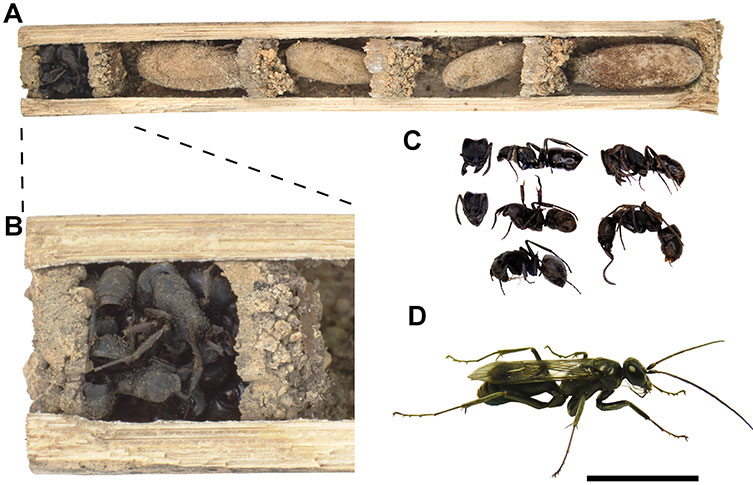

The bone-house wasp (Deuteragenia ossarium) uses ant carcasses to protect its nest. Image © Merten Ehmig (A,B) Michael Staab (C,D) via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 2.5

One of the eeriest collectors of the natural world, the bone-house wasp gets its name from its preference for macabre building supplies. Discovered in southeast China in 2014, this unusual wasp packs the walls of its nest chambers with the corpses of ants.

Bone-house wasps seek out existing cavities, such as beetle boreholes, and transform them into fortress-nests for their larvae. While adult wasps survive on an innocuous diet of nectar, their offspring have an appetite for fresh spider flesh.

Hard-working mothers gather live spiders by paralysing them and bricking them into a small cell cavity with their larvae. Before abandoning her young, the mother will place the final touch on her catacomb-like design by packing the entryway with ant corpses and sealing the door.

Why does the bone-house wasp collect ant corpses?

Neither the wasp nor offspring eat ants, which makes this collecting behaviour highly unusual. Scientists believe the ants are used as a clever ruse to defend the unguarded nest against parasites.

Ant exoskeletons are covered in toxic chemicals that remain on their bodies long after death. The smell of the ant bodies could disguise the wasp nest as an ant colony or pack a toxic punch to curious predators that venture too close.

Mad hatterpillar

The caterpillar of the gum-leaf skeletoniser moth, known colloquially as the mad hatterpillar, retains old head exoskeletons after each moult to refashion them into a bizarre tapering hat. © Katarina Christenson/ Shutterstock

As a caterpillar, Uraba lugens changes its exoskeleton up to 13 times. But from the fourth instar, it begins to retain the empty head casings it outgrows. These are bound together, creating what looks like a towering hat that grows taller each time the caterpillars shed. This has led to them being commonly referred to as the mad hatterpillar, a play on the character from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Found in Australia and New Zealand, this eccentric caterpillar is also known as the gum-leaf skeletoniser, so named for its habit of stripping the juicy blades of eucalyptus leaves down to skeletal twigs and vein structures.

Why does the mad hatterpillar keep its heads?

Scientists believe that the caterpillar evolved its over-the-top dress code for defence against predators.

The retained head exoskeletons are a false target, diverting predators' attacks to non-vital body parts. The tower on the head also makes the caterpillar appear larger and functions as a weapon to fend off attackers.

The caterpillar's body is covered with hairs that cause irritation (urticating hairs). These are a formidable defence against many vertebrate predators. Their headgear may have evolved as extra protection, mainly for defence against enemies that are not deterred by their hairy covering, such as parasitoid flies and wasps, predatory bugs, spiders and other predatory invertebrates.

Decorator crab

Spiny spider crab (Achaeus spinosus) decorated with anemones. Image © Rickard Zerpe via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

There are many species of decorator crabs that collect and arrange materials from their environment to fashion into elaborate disguises - sometimes even using living creatures.

To help facilitate their grand designs, their carapace (hard upper shell) is covered in small hooks known as setae. These allow the animals to affix seaweed, anemones, sea urchins and anything else they collect that could be useful camouflage within their local environment.

When a suitable addition is found, the crab will snip it from its current tethering with its pincers, coat the base with a special secretion that hardens in seawater and place it deliberately on its shell.

When decorator crabs outgrow their shell and moult, they will often painstakingly relocate their prized living collection to their new shell as it hardens.

Why do decorator crabs decorate?

Maintaining a harmonious collection of materials from their immediate environment, on the reef or sea floor, is for camouflage. It helps decorator crabs disappear into the landscape and make themselves invisible to predators.

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

%20sbs-landscape.jpg)

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media