Bed bugs are small (4–5 mm long and 1.5–3.0 mm wide), oval, flattish insects with needle-like mouthparts which pierce the skin of mammals and birds to suck their blood. Usually bed bugs are mahogany-brown in colour but they become deep purple or red after a meal.

© Gilles San Martin Harvard University, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Bed bugs are well-known human pests. The commonest species in temperate and sub-tropical regions is Cimex lectularius (the common bed bug), found in domestic houses. In Britain, there are three other species that are parasitic on birds and bats.

What do bed bugs look like?

Adult bed bugs are small (4-5 mm long and 1.5-3 mm wide), oval and flattish. They are usually mahogany-brown in colour but they become deep purple or red after a meal.

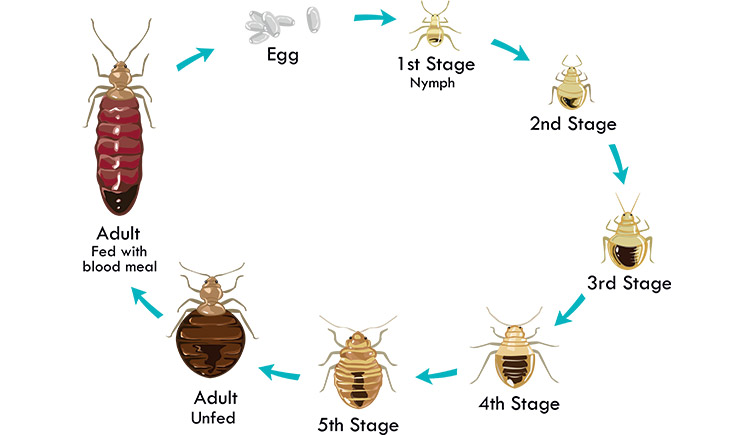

Immature bed bugs are the same overall shape but smaller. They start off nearly colourless but become browner as the mature.

Once hatched, a bed bug has five immature stages before reaching adulthood. A bed bug's abdomen can swell and appear red immediatelyafter feeding. Image © Shutterstock/Crystal Eye Studio

Distribution

The common bed bug may have originated around the Mediterranean, but it has been carried by people throughout the world. Despite efforts to eradicate it, the insect is still present in Britain, including large cities like London and is making a comeback everywhere in the world.

Activity and life cycle

Bed bugs are mainly nocturnal and reach peak activity before dawn. They respond to warmth (eg central heating) and carbon dioxide but not odours. They rest and lay their eggs in crevices and behind wallpaper. When seen on a wall, they resemble mobile brown lentils. Although flightless, bed bugs can run extremely fast, particularly in warm weather.

Their presence can be detected by specks of faeces and their odour.

Bed bugs lay their eggs after feeding and mating. Females lay around 150 eggs over the course of their lives. Bed-bugs are long-lived and can last for a year or more without feeding.

How bed bugs mate

Bed bug bites

The nocturnal biting of bed bugs can be debilitating to humans whose sleep is disturbed every night (their feeds last for five minutes or more).

The constant irritation is due to the injection of minute doses of bed bug saliva into the blood and can contribute to ill-health of children and even adults. Some fortunate people are not affected by the bites of bed-bugs. Others gain immunity after repeated biting, whilst others, less fortunate, are always susceptible. Fortunately, in Britain, the bite is not known to be the cause of disease transmission.

An adult bed bugingesting a blood meal from the arm of a human host © CDC/ Harvard University, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Control of bed bugs

The climate of Britain is relatively unfavourable for bed-bugs (at least in unheated bedrooms) for a considerable part of the year. Consequently, heavy infestations in this country are only likely to develop in the favourable warmth of centrally heated buildings and then only when undisturbed by proper housekeeping cleanliness.

Nearly all advisory articles on bed bug control stress the value of household hygiene. It is doubtful whether many bugs are actually killed by the soap and water which is generally advocated, though no doubt some bugs and eggs would be destroyed mechanically by scrubbing. The essential importance of good house cleaning is the early discovery of bug infestations which can then be eradicated in the early stages.

Small invasions of bed bugs can occur in any household, for example, as a result of buying second-hand furniture. However the risk is greatest in hotels and guest houses, due to the transient nature of the occupants, who may bring in bugs in their luggage (especially travellers from warmer countries).

The main value of regular and thorough house cleaning is the early discovery of the infestation, before the bugs have had the opportunity of becoming dispersed in numerous inaccessible harbourages.

On discovery of a number of bugs, a thorough search should be made to discover the full extent of the infestation. A light should be used to examine crevices and other likely places. In addition to thorough cleansing, a good household insecticide should be sprayed into crevices and corners as well as mattresses.

More information

Download this information sheet on the bed bug as a PDF (300KB)

Elsewhere on the internet:

Common insect pest species in homes

Back to the Common Insect Pest Species in Homes guide

Identify your finds 🔍

Need help in indentifying what you've seen?

Our ID guides and expert team are here to assist you.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media