The world’s rarest mineral resources are in your hands.

Mobile phones, laptops and computers need precious metals and minerals to function – but Earth only has a limited supply. Image © Akhenaton Images/Shutterstock

There’s an ever-growing demand for electronic devices and it’s putting pressure on supply chains and the planet. Our insatiable appetite for the latest technology comes at a price.

Professor Richard Herrington, who leads research into ‘Resourcing the Green Economy’ at the Natural History Museum, invites us all to take a critical look at the gadgets we love and appreciate the vital materials they’re made of.

“I think most people don’t have any idea of the range and scale of metals and minerals that are used to make electronics,” says Richard. “We’ve found use for them in computers, cars and all kinds of machinery – it’s technology that we didn’t have 15 or 20 years ago that we now take for granted.”

“It’s really important that we all understand where the raw materials come from, that metals and minerals are in Earth where nature puts them. They don’t come from a factory and the supply is dispersed around the world where sometimes business and environmental practices aren’t the best.”

Richard hopes that by learning where these valuable resources come from and how they are being extracted, people will place more value on what they already have, understand the environmental – and human – cost of cheap electronics, reduce their own waste and make choices that in turn force manufacturers to lift their standards.

Metals and minerals for green technologies

We don’t just need these materials for our phones. We also need precious metals and minerals to make technology that’ll help us make Earth a cleaner, greener place.

“We all acknowledge that we need to stop burning carbon for our energy. Alternatives like wind turbines, solar panels, hydro-electric dams and electric cars call for new technologies that also demand metals and other materials,” says Richard.

Green technologies, such as electric vehicles and wind turbines, require metals for wiring, batteries and components including copper, lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel and graphite. Solar panels also call for metals such as tellurium and silicon for the solar cells that turn sunlight into electricity.

“We’re expanding the amounts that we need of these materials, and there’s still a question around whether we can get enough in time to implement the changes we’ve promised for the planet.”

Which minerals are in your mobile?

1. Copper

Copper in its raw nugget form. Image © Jonathan Zander via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

What’s copper used for? Copper is a vital element used in wiring for all kinds of electronics. It conducts electricity and heat very efficiently. It’s needed in larger amounts than any other metal in your mobile phone. There will have to be an increase in its supply to meet the world’s growing demand for electronics.

Where does copper come from? Copper is mostly sourced from open-cut mines. Chile is the world’s largest supplier of copper, but the metal is produced elsewhere in North and South America too.

2. Tellurium

A small disc of metallic tellurium. Image of tellurium via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

What’s tellurium used for? Adding tellurium to other metals improves their strength and hardness, and reduces corrosion. It can also be used for tinting glass and is vital for manufacturing of solar panels.

Where does tellurium come from? Tellurium is found in copper ore and most often extracted as a by-product of copper processing. Tellurium is mined in Japan and Canada.

3. Lithium

Lithium ingots with black nitride tarnish. Image © Dnn87 via Wikimedia Commons licensed under CC BY 3.0

What’s lithium used for? Lithium is essential to the production of cathodes in the lithium-ion batteries used in many rechargeable devices.

Where does lithium come from? Lithium is found in rock and salt lakes called salars, which are mined or pumped out before chemical extraction. Leading producers include Australia, Chile, Argentina and China. Demand for lithium is expected to expand rapidly as demand grows for environmentally friendly technologies.

4. Cobalt

Elemental cobalt. Image © Jurii via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

What’s cobalt used for? Cobalt is important for rechargeable batteries, circuits and a range of other electrical components. Coating microscopic copper wires with cobalt makes microchips more reliable.

Where does cobalt come from? More than half of the world’s cobalt supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Most of the production that takes place in the Democratic Republic of Congo is done properly, but there’s still a potential for cobalt mining from child labour coming into the supply chain and the market should be making sure that doesn’t happen,” Richard says.

He believes we need to make sure the supply of cobalt is spread more evenly around other parts of the world so that we don’t have such enormous reliance on one country.

5. Manganese

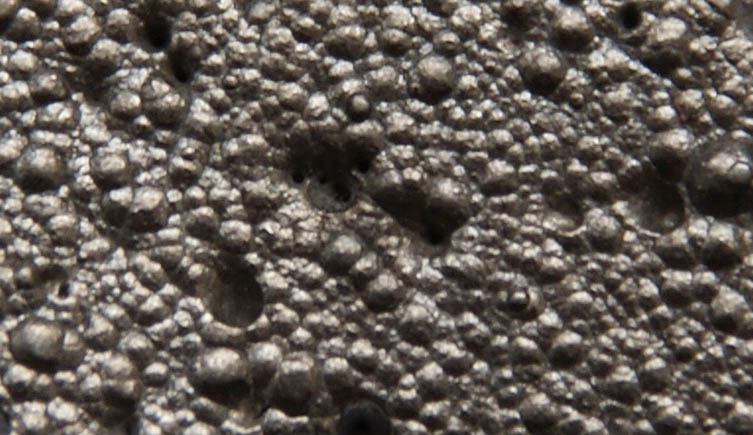

Manganese in various forms. Image © Alchemist-hp via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under FAL 1.3

What’s manganese used for? Used extensively for television circuit boards and dry-cell batteries, manganese can make electronics more resilient. The next generation of rechargeable batteries is likely to use more manganese.

Where does manganese come from? Although manganese is abundant in Earth’s crust, 80% of the world’s supply comes from South Africa. It’s also mined in Australia, China, India, Ukraine, Brazil and Gabon.

6. Tungsten

A cube of pure tungsten and two tungsten rods with evaporated crystals. Image © Alchemist-hp via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under FAL 1.3

What’s tungsten used for? Tungsten is a highly dense and durable metal, four times harder than titanium. It’s used as a weight in a phone’s vibrator.

Where does tungsten come from? A staggering 75% of the world’s tungsten comes from China. Other producers include North America, South Korea, Bolivia, Russia and Portugal. Tungsten is extracted from the minerals wolframite and scheelite.

It’s time to look at our supply of raw materials

Our globalised marketplace keeps prices relatively low, but at a cost – a vulnerable supply chain and, in some cases, reliance on countries with histories of exploitative workplace practices and child labour.

“What we really don’t want to happen is that the metals and materials we use come from only one place or only one company in the world,” Richard explains. “Narrow supply opens up the possibility of commercial and geographical monopolies being created.”

“In the past we’ve had problems with monopolies inflating prices and there’s the risk as well, given where they might be coming from, that these mining organisations aren’t following best practice.”

According to Richard, the UK’s supply of lithium is currently stable but the cobalt supply is more uncertain.

“At the moment, 30% of our lithium comes from South America including Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, and another third comes from Australia, with the rest made up by a few other suppliers.”

“Lithium is distributed among various countries, so the supply of that is quite diverse and secure. However, around 70% of cobalt comes from a single source – the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country that’s had its share of political problems and evidence of some child labour, which as consumers we should be concerned about.”

Should we bring more primary production home?

Richard believes there is huge potential in looking closer to home for our mineral supply.

“When you can source minerals locally, you know the supply chain is short and can be better controlled. The risk of unethical practices drop and you can cut down on the environmental and other costs of transportation,” he says.

“Unfortunately, we have a tendency to be ‘NIMBYs"’ when it comes to mining, saying things are okay if it’s ‘not in my back yard’ – but isn’t exporting the problem worse?

“I think we can take the example from agriculture. People are happy eating food that’s produced locally and I think we should be equally conscious about how we source raw materials from Earth.”

Towards a circular economy

Richard believes we should be building a circular economy that minimises or eliminates waste by returning precious resources into the production cycle.

“Rather than creating things like mobile phones, using them for a while and putting them in a drawer when we buy a new one, we have an obligation not to lose track of where those precious materials are, and to ensure we are making products in forms that can be readily recycled,” Richard says.

“We shouldn’t be wasting resources. We should make sure that once we pull them out of the ground we look after them and use and reuse them.”

More information

- Discover more about our work on critical elements.

- We’re helping to secure lithium supplies for the UK. Find out more.

- To meet UK electric car targets for 2050, we’d need just under twice the current annual world cobalt production. Read the findings.

Ways to live more sustainably

Use our new tool to find actions that are good for both you and the environment.

Fixing Our Broken Planet

Discover science-backed, hopeful solutions that will help us to create a more sustainable world.

New gallery open now.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media