A wasp spider (Argiope bruennichi) on its orb web

© AlisLuch/Shutterstock.com

What are spider webs made of? And how do they spin them?

Lisa Hendry

Find out how web-spinning spiders do what they do and learn about the impressive, multipurpose material they use to catch their dinner.

Spiders make their webs from silk, a natural fibre made of protein.

Not only does spider silk combine the useful properties of high tensile strength and extensibility, it can be beautiful in its own right.

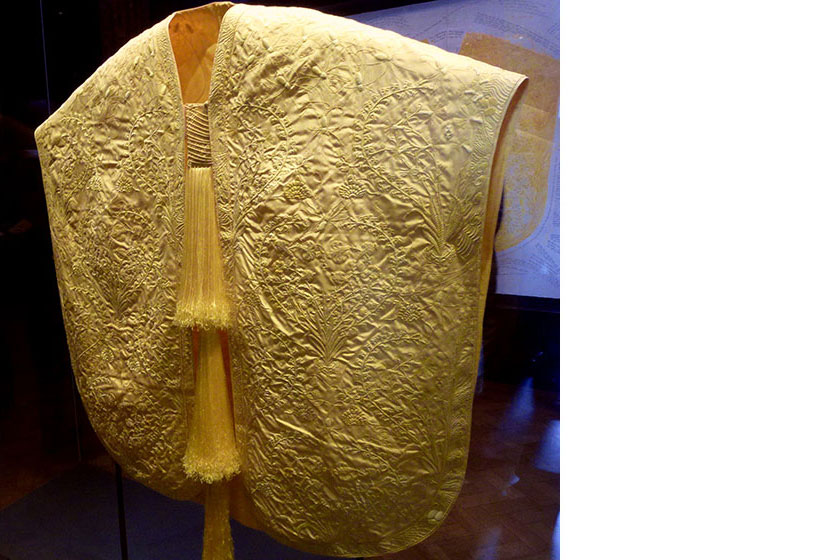

'Silk is an amazing material,' says Jan Beccaloni, our arachnid curator. 'Golden silk orb-weavers, which are found in warm regions around the world - but not the UK, unfortunately - spin webs with a lovely golden sheen. Their silk has even been used to create a shimmering golden cape that was exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2012.'

UK spiders tend to produce silk that is white or has a bluish hue.

There are seven different silk glands, which produce silk with different characteristics and uses. For example cribellate silk is very woolly.

Jan adds, 'Cribellate silk acts like Velcro, sticking to the legs and bristles of captured insects.'

Each type of silk gland is associated with a particular spinneret. No species has all seven, but orb-web weavers have five.

Golden silk orb-weavers (Nephila species) spin silk with a brilliant yellow colour

© Claire E Carter/Shutterstock.com

A golden cape woven from spider silk, which was exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2012

© Cmglee (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

How do spiders make their webs?

A spider spinning silk to make its web, pulling the thread out with its hind leg

© Ian Fletcher/Shutterstock.com

Spiders have structures called spinnerets on their abdomen, usually on the underside to the rear. These are the silk-spinning organs. Different species have different numbers of spinnerets, but most have a cluster.

At the end of each spinneret is a collection of spigots, nozzle-like structures. A single silk thread comes out of each.

Jan explains, 'Although it looks a bit like an icing nozzle, the silk is pulled out by gravity or the spider's hind leg. The silk is liquid when it's inside the spider.'

Before it is extruded out of the spinneret, cribellate silk first passes through a sieve-like structure called the cribellum. Spiders that make this type of silk also have a row of specialised leg bristles called the calamistrum, which combs the silk out and gives it the different, woolly texture.

Spiders then follow various patterns of activity to construct their webs, depending on what species it is. It's fascinating to watch.

Do all spiders make webs?

Although webs are the most well-known use for spider silk, not all spiders make webs to catch their prey. In fact, less than half of the 37 spider families in Britain do.

Other spiders, such as crab spiders in the family Thomisidae, are 'sit and wait' predators - for example Misumena vatia lurks on flower heads, waiting to ambushing visiting insects. Others, such as jumping spiders in the family Saltidae, actively follow their prey and catch it by leaping on it.

A crab spider, Misumena vatia, ambushing prey from its flower vantage point.

Image courtesy of Pixabay (CC0).

A jumping spider, Salticus scenicus, attacking a fly

© Adam Opiola (CC BY-SA 4.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Some spiders even invade other webs to find their food. The pirate spiders, of which there are four UK species in the genus Ero, go onto another spider's web and mimic the behaviour of its prey to lure the spider closer. When the web's owner investigates, the pirate spider attacks.

Silk: a multipurpose material

However, even spiders that don't make webs have uses for silk, including creating moulting platforms, sperm webs for males, and retreats.

Jan adds, 'Jumping spiders, for example, make little silken cells in which to hide in during the day - a bit like a sleeping bag.'

Most spiders use silk to wrap their eggs.

Another common use for silk is as a drag line. Every so often a spider attaches a thread of silk to something, like an anchor, so that if it falls, it won't fall too far and can drag itself back up to the previous position.

Ballooning is another spectacular use for silk, allowing the mass dispersal of spiderlings and small adults.

After climbing to a relatively high point, the spider points its abdomen skywards and pulls out one to several threads. When air or electrostatic currents carry the threads upwards, the spider follows. They can be carried many thousands of metres.

Money spider mass dispersals in particular make quite a sight. Sometimes the numbers involved can leave an entire field coated in gossamer threads.

Jan says, 'Not all spiders disperse this way, but it's the reason spiders are some of the first creatures to colonise new islands.'

More spider web facts

Now that you know how spiders make their webs, discover their impressive variety. British spider webs can be grouped into seven broad types based on their architecture: orb, sheet, tangle, funnel, lace, radial and purse. But even within each group, different species put their own spin on the style.

The diving bell spider (Argyroneta aquatica) probably has the most unusual use for its web, which enables it to spend most of its life underwater - a unique ability among spiders. It constructs a net of silk between submerged vegetation and uses it to gather a bubble of air - its very own diving bell.

View the common styles of web and the spiders that make them >

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media