They could beat a horse in a race and survive a blizzard. No challenge is too much for these butterflies and moths.

Painted lady butterflies are in the record books thanks to their long migrations, covering thousands of miles. © Cathy Keifer/Shutterstock.com

Beating the competition is everything. It’s forced some species to grow faster, higher, stronger and bigger to win first prize in the survival stakes.

Our butterfly curator Dr Blanca Huertas explains the secrets behind their success.

Skippers are speed champions. © David J Martin/Shutterstock.com

Fastest butterfly: Skipper

Skippers are natural sprinters. They can reach speeds of up to 37 miles per hour (59 kilometres per hour) and have some of nature’s fastest reflexes. They could keep pace with a horse in a race and they get their name from their quick flight patterns.

There are nearly 4,000 different species of skipper, found everywhere in the world except Antarctica.

Researchers have recently found that when skippers are startled, they react at least twice as quickly as a human does.

“Fast reactions and flight speeds help skippers deal with danger and avoid predators,” says Blanca.

Bright green Queen Alexandra’s birdwing butterflies shimmer in their rainforest home. Image © Mark Pellegrini via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Biggest butterfly: Queen Alexandra’s birdwing, Ornithoptera alexandrae

Female Queen Alexandra’s birdwings are the biggest butterflies in the world, boasting a wingspan of around 27 centimetres.

The endangered species lives in the rainforests of northern Papua New Guinea and plays an important role in the ecosystem.

Its large size means it’s able to pollinate bigger plants that other insects cannot manage. Sadly, its habitat is being rapidly cut down to make way for palm oil plantations.

The females are dark brown with cream patches and yellow abdomens. Males are bright green.

“The largest recorded specimen, which has a wingspan of 27.3 centimetres, is in the Lepidoptera collections we care for,” says Blanca.

“The specimen was collected in late 1800s, but still looks like it was collected yesterday.”

Painted ladies can adapt to dozens of different environments. © Gary L Brewer/Shutterstock.com

Longest migration: Painted lady, Vanessa cardui

The relay team of the butterfly world is the painted lady species. These incredible insects complete an impressive 9,000 mile (14,480 kilometre) journey from tropical Africa to the Arctic Circle.

One butterfly alone couldn’t manage the journey, so it’s completed in stages. Up to six successive generations spend their lives flying north.

The painted lady recently took the crown for the longest journey from the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus, which migrates annually from Canada to Mexico and California.

Painted ladies are some of the most widespread butterflies in the world, found across every continent except Antarctica and Australia.

They’re happy in many habitats, from mountaintops to beaches, finding it easy to adjust from bogs to deserts and dunes to rainforests.

“The painted lady’s ability to adapt to a wide range of environments means it’s able to thrive and reproduce successfully. It’s one of the most interesting butterflies in the world – and beautiful, too,” says Blanca.

Darwin predicted the existence of this creature years before it was found. Image © kqedquest via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Longest proboscis: Morgan’s sphinx moth, Xanthopan morganii

A proboscis is the elongated mouth part that butterflies use to feed on nectar hidden inside flowers.

The Morgan’s sphinx has a proboscis that measures a foot – roughly 30 centimetres – in length. It’s the only pollinator of the Madagascar orchid, an unusual flower in which the nectar is kept at the bottom of a long spur.

Charles Darwin predicted the existence of this creature before it was even discovered, after he studied the species of orchid it feeds on.

He knew that any flower keeping its nectar so well-hidden would need a corresponding unusual pollinator. Darwin died in 1882, but the moth was not discovered until 1903.

“The plant and the moth are perfectly suited to each other, each supporting the other’s survival,” says our hawkmoth expert Dr Ian Kitching.

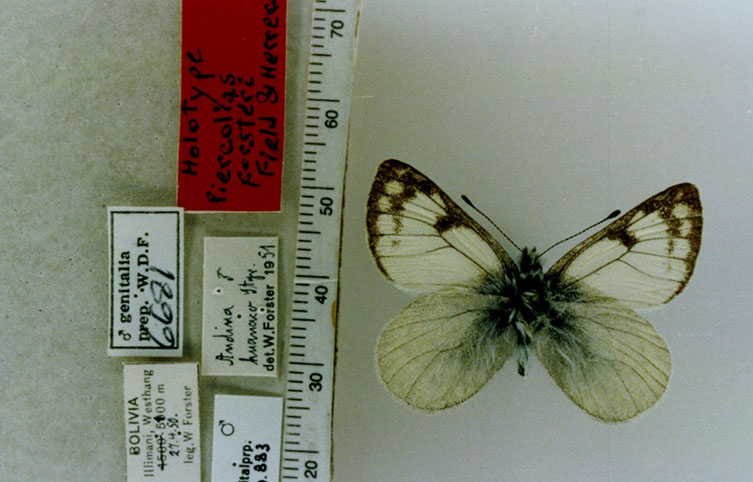

Piercolias forsteri may be tiny, but it’s a high jumper, soaring higher than any other butterfly. © Gerardo Lamas/The Bavarian State Collection of Zoology

Highest-flying: Piercolias forsteri

Piercolias forsteri flies in the high Andes mountains of Bolivia in South America, about 4,200 metres above sea level.

This butterfly roams peaks that are covered in rocks, ice and snow, with little vegetation.

Several related species fly at similar heights, braving extreme temperatures.

When naturalist Gustav Garlepp discovered the closely-related Piercolias huanaco, he’s said to have remarked, “I cannot understand its choosing such wastes and deserts, or how it can exist there at all.”

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media