Zombie-ant fungi are named for their ability to manipulate the behaviour of their insect hosts.

Two newly described species of ancient fungi from the age of dinosaurs are now shedding light on the origins of these deadly parasites.

A Cretaceous ant discards a pupa infected with fungi. © Dinghua Yang

Zombie-ant fungi are named for their ability to manipulate the behaviour of their insect hosts.

Two newly described species of ancient fungi from the age of dinosaurs are now shedding light on the origins of these deadly parasites.

Fungi that feed on living animals are not exclusive to the realms of science fiction, and it seems they have been doing it for a very long time.

Scientists have described two new species of ancient fungi that were found preserved in amber growing out of the bodies of their insect hosts.

The insects met this unfortunate end almost 100 million years ago during the Mid- Cretaceous, making these among the oldest known examples of parasitic fungi that infect insects.

The incredible preservation has allowed researchers to describe the new species and identify their host insect. The first, which has been named Paleoophiocordyceps gerontoformicae, was found bursting from the body of a young ant, and the second, P. ironomyiae, on a fly.

Scientists observed that the newly described species of Paleoophiocordyceps appear to share several common traits with living species of Ophiocordyceps, which is the group of fungi that contains the zombie-ant fungus. Evidence suggests that these two groups may have diverged from each other over 130 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous.

Ophiocordyceps are named because they infect the brain of their hosts to then manipulate the ant’s behaviour. Zombie-ant fungi have gained widespread recognition as the inspiration behind the post-apocalyptic video game and TV series The Last of Us.

Professor Edmund Jarzembowski, a co-author of the study, says, “It’s fascinating to see some of the strangeness of the natural world that we see today was also present at the height of the age of the dinosaurs.”

“This discovery shows the impact of tiny organisms on social animals long before humans evolved - with the comforting thought that these tiny organisms are unlikely to jump to us, unlike in sci-fi films!”

The amber specimens are currently held at Yunnan University and Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. A description of the new species has been published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Fungi can be seen growing out of the head of an insect encased in 99-million-year-old amber. © Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Insects and fungi have evolved complex relationships during the 400 million years they have coexisted. These can be mutually beneficial, such as when some species of ants farm fungi, or entirely ruthless when fungi turn on insects.

Known as entomopathogenic fungi, they can infect a wide range of insect groups, including ants, flies, spiders, cicadas and beetles. Their broad choice of hosts makes these fungi an important regulator of insect populations in many ecosystems.

These parasitic fungi come from various groups and so are believed to have evolved multiple times independently. More than 1,500 species are currently found in five out of the eight major groups of fungi.

But out of all the entomopathogenic fungi, those found in the Ophiocordyceps genus are among the most intriguing. One of the most famous members of this group is the zombie-ant fungus, Ophiocordyceps unilateralis.

The spores of the O. unilateralis fungus will penetrate the exoskeleton of an ant and will gradually take over its host’s behaviour, forcing it to seek out more favourable conditions for the fungi’s own growth. The infected ant will find a place above the ground and sink its jaws into the stem or leaf of a plant, known as the death grip. Here, it waits as the fungus devours it from the inside.

After the ant dies, the fungus grows out of the insect’s body and releases millions of spores that infect more ants. The higher vantage point to which the ant has climbed provides the ideal launch pad to ensure the greatest distribution of spores.

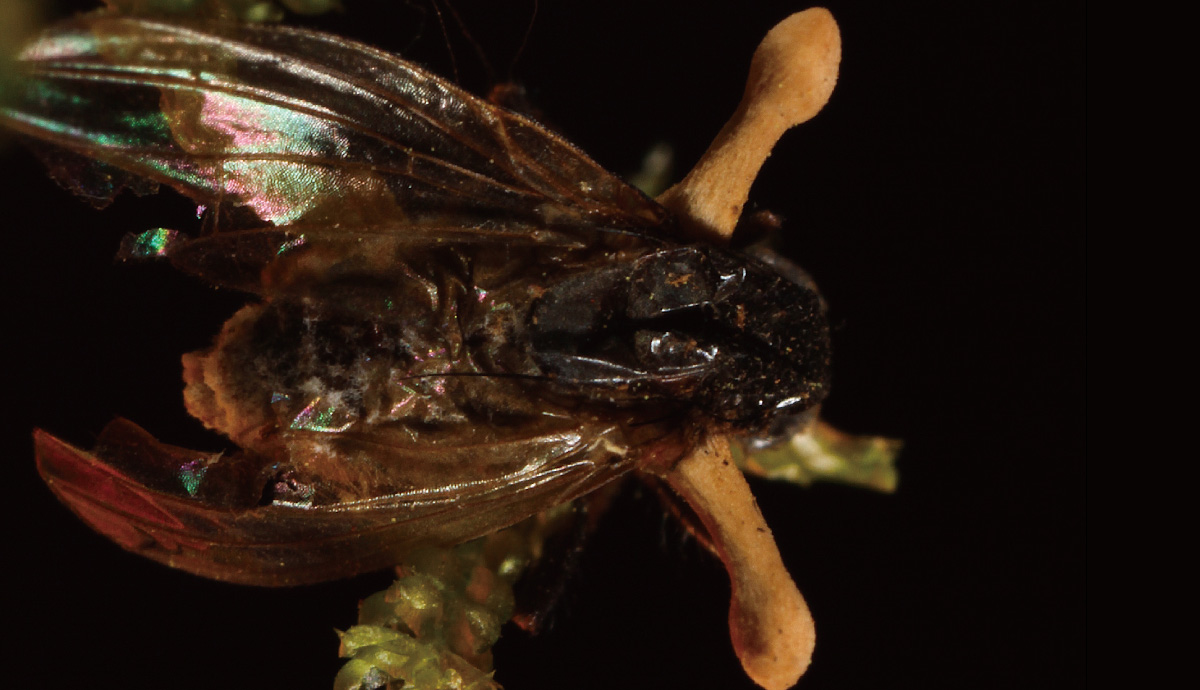

A living species of Ophiocordyceps grows out of an infected fly. © Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Although parasitic fungi are widespread in today’s ecosystems, finding fossil evidence of them is rare. This is because their fragile, soft tissues do not preserve well in fossils, while their parasitic lifestyle means they can be difficult to identify among insect remains.

Very few specimens of ancient parasitic fungi have been discovered, and so we know very little about their evolution. This latest discovery offers a rare glimpse into these parasites from a long time ago.

The new specimens were preserved in amber, which formed when tree resin enveloped the infected insect, fossilising both host and parasite together.

The oldest fossil evidence of Ophiocordyceps dates back to the Eocene, almost 50 million years ago. But this latest find suggests that Paleoophiocordyceps and Ophiocordyceps diverged over 130 million years ago, pushing back the origin of this group by tens of millions of years.

This fits in with how scientists have previously thought that these fungi evolved. While many modern species of Ophiocordyceps are highly specialised to infect a particular group of insect hosts, studies suggest that its ancestors may have originally infected beetles.

Beetles diversified alongside the early dinosaurs during the Triassic and Jurassic periods. They inhabited decaying wood, soil and leaf litter, environments that are also ideal for fungi. This could have created the ideal conditions for Ophiocordyceps to establish beetles as their hosts.

As other insect groups evolved and diversified hundreds of millions of years ago, the fungi likely made a host jump to other animals, including ants, flies, moths, and butterflies.

“The fossil evidence shows that the infectious fungi were already adapted to two different insect hosts a hundred million years ago, an ant and a true fly,” says Ed. “This suggests that the fungus made this jump to other insects as they diversified with the rise of flowering plants and new insect groups, especially moths and butterflies.”

“As the infections are lethal, Ophiocordyceps likely played an important role in controlling the populations of insects by the Mid-Cretaceous, in a similar way to how their living counterparts do today.”

The oldest fossil evidence of zombie fungi comes from a 48-million-year-old leaf which shows scars from the death grip of an unfortunate ant that was likely infected and manipulated by fungi.

“What we need to do now is examine Cretaceous leaves for evidence of death grips to see if fungal behaviour manipulation evolved during this time.”

Find out what our scientists are revealing about how dinosaurs looked, lived and behaved.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media