A portrait of Sir Hans Sloane, a respected physician and naturalist whose collections and library were acquired by the nation in 1753.

undefinedHans Sloane: Physician, collector and botanist

Katie Pavid

Sir Hans Sloane was a seventeenth-century doctor and collector who amassed such a vast amount of material that it eventually formed the basis of our collection.

The early life of Hans Sloane

Hans Sloane was born in 1660 Killyleagh in County Down, Northern Ireland, the youngest of seven sons born to Alexander and Sarah Sloane.

He was reportedly a curious child, fascinated by the plants and animals around him. In later life he recalled how he had ‘from my Youth been very much pleas’d with the study of Plants and other Parts of Nature’.

In 1679, aged 19, he moved to London to study chemistry at the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London and botany at the Chelsea Physic Garden, laying the foundations for his future prosperous career as a physician. He became friends of celebrated botanists of his day, including John Ray.

In 1683 Sloane left London to tour France, where he studied anatomy, medicine and botany and received his Doctorate of Physics.

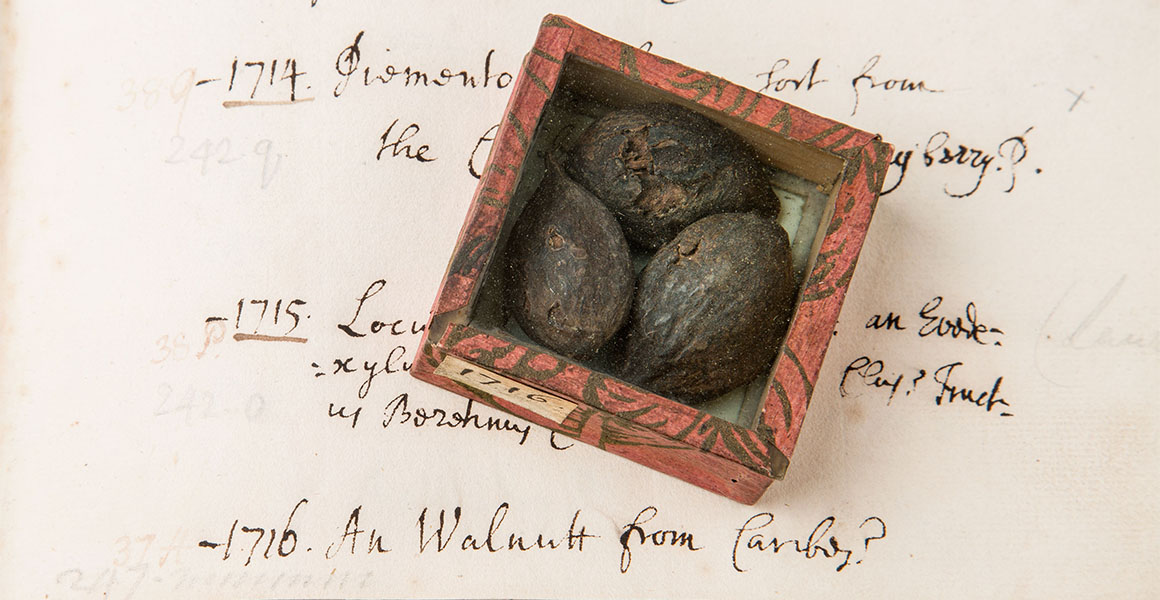

A walnut specimen that Hans Sloane collected from the Caribbean, shown here alongside the catalogue entry. Sloane's original entry reads: ‘1,716. An Walnutt from Caribes?’

In France he met and befriended more of the great botanists and physicians of his time, notably Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and Monsignor Magnol. He was intrigued by the search for species that the two men were pursuing.

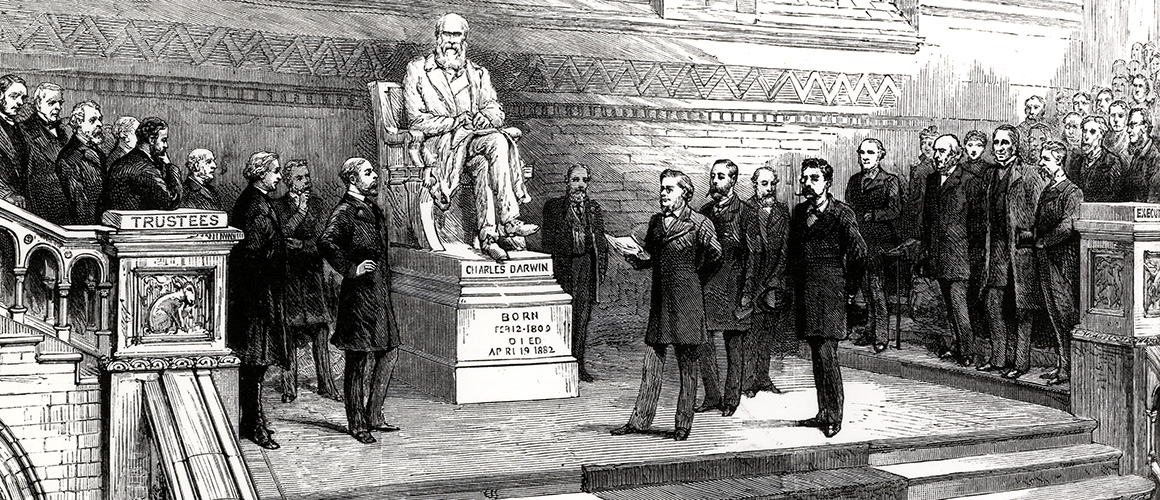

After his return to London, Sloane was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1685. He would later become the Society’s Honorary Secretary and President. Two years later, he was also made a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Hans Sloane in Jamaica

At the age of 27 Sloane went to Jamaica as personal physician of Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle and newly appointed governor of the island.

By the time Sloane arrived, Jamaica was an English royal colony. Sloane’s employer was there to help establish imperial control.

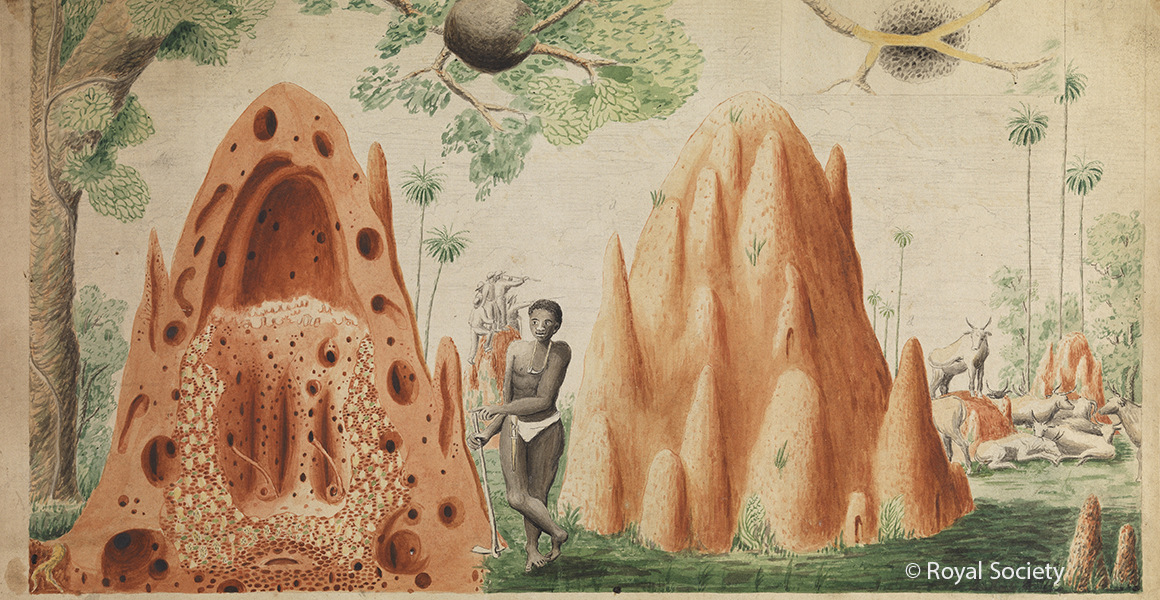

His 15-month visit to the country came in the middle of the transatlantic slave trade, which enslaved between 10-12 million African people between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Many of the enslaved Africans who were brought to Jamaica during that period were Akan, from modern-day Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.

While in Jamaica, Sloane collected more than 800 plant specimens, live animals, shells and rocks, and wrote notes on local plants, animals and customs.

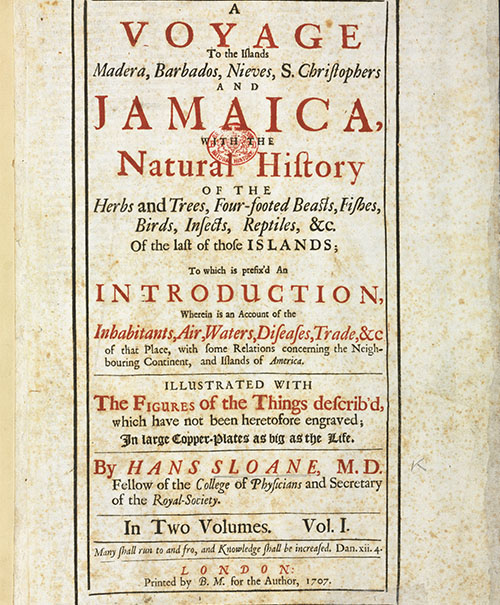

The frontispiece of Sir Hans Sloane’s Voyage of Jamaica, an account of the natural history of Jamaica and its neighbouring islands. It was published in London in 1707.

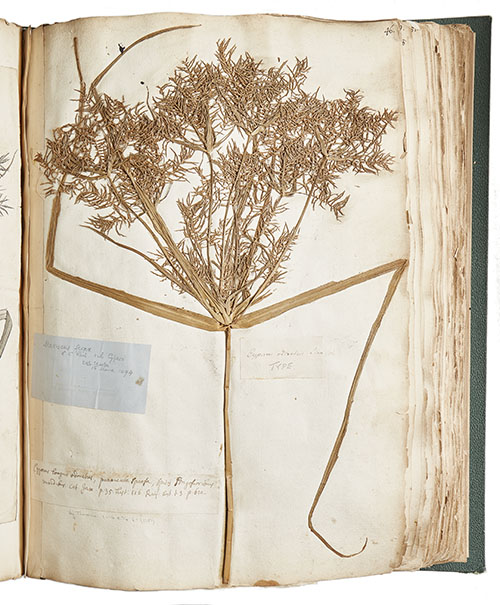

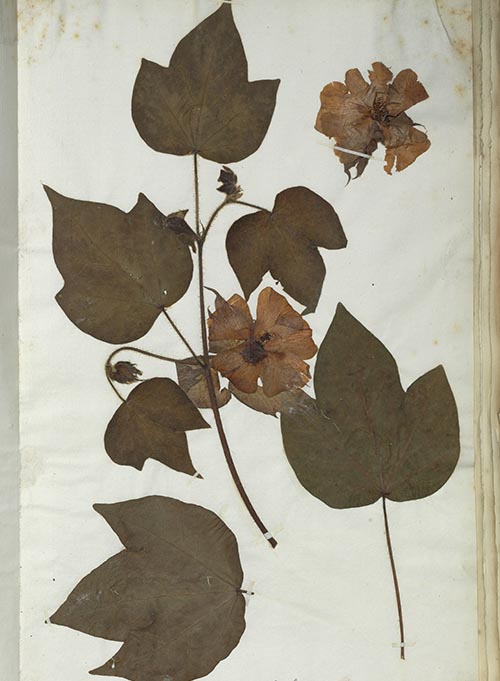

A sedge plant specimen that Sloane brought back to London from Jamaica, inside one his many volumes of plant material.

Enslaved people assisted Sloane in acquiring some of his precious specimens. In some cases, their knowledge and skills were fundamental to Sloane’s discoveries. They played a key part in enabling Sloane’s long and prosperous collecting career.

While his personal views on slavery are unclear, Sloane wrote in detail about enslaved Africans’ knowledge of plants. He appears not to have valued their medical traditions and interpretations, however.

Written records also reveal that Sloane described various aspects of enslaved Africans’ lives and collected their cultural artefacts, including musical instruments. His writings touch on the slave trade as well as the transfer of plants by slave traders from West Africa to Jamaica.

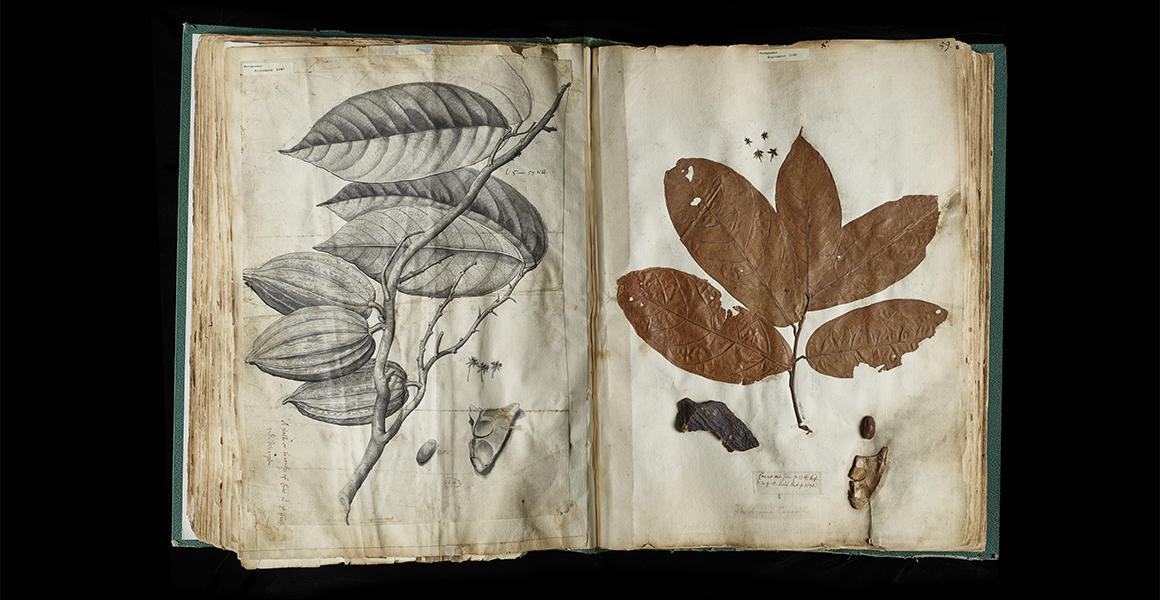

A botany sheet showing a cocoa plant brought back from Jamaica in 1689 by Hans Sloane. The illustration was completed by Dutch artist Everhardus Kickius.

Following the death of the Duke, Sloane returned to England in 1689. He then began to work on the collections and information he had gathered in Jamaica. In 1696 he published a list of the plants he had collected, the Catalogus Plantarum. He took his pressed and dried plant specimens back to London and pasted them into seven large books.

Perhaps Sloane’s best-known work is his publication Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers, and Jamaica. The first volume, published in 1707, had a strong botanical focus. It was followed in 1725 with another volume, this time examining the fauna of Jamaica and also wider themes such as disease, trade and climate.

Who invented hot chocolate?

Sloane is often thought of as the inventor of drinking chocolate with milk. But historians note that Jamaicans were actually making a hot beverage, brewed with shavings of cocoa, milk and cinnamon as far back as 1494, long before Sloane’s arrival in Jamaica.

Our curator Miranda Lowe takes a closer look at the legacy of colonialism at the Museum and explores the true origins of hot chocolate. Discover more contributions of Black people to the field of natural history. Video with audio description (4 minutes 53 seconds).

Dr Sloane

Once back in London, Sloane set up a medical practice. He was a highly esteemed physician and was appointed Physician Extraordinary to Queen Anne and King George I, and Physician in Ordinary to King George II.

He married Elizabeth Langley Rose in 1695. She was a wealthy heiress and the widow of Fulke Rose, a plantation owner in Jamaica. The couple had three daughters and one son, although only two of the children survived to adulthood.

His wife’s fortune allowed Sloane to continue his work. Over the years his collection grew until whole rooms in his house were filled with tens of thousands of plants, animals, gemstones, coins and antiquities. He also had 50,000 books, prints and manuscripts.

Sloane’s medical and scientific careers were directly funded by profits from slavery. The links between his collection and the slave trade did not end when he left Jamaica.

It is clear that trade, in both commodities and human lives, provided the infrastructure that allowed Sloane and his contemporaries to build their collections of natural history objects. Slave traders, slave-ship surgeons and others were among those supplying specimens to Sloane and others.

Many of the collections built by other men ultimately ended up with Sloane. He amassed a large fortune and became one of the most influential people in London.

His house also became a major attraction. Although not open to the public, it was visited by a stream of interested people from Britain and abroad. One in particular was the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who would later use Sloane's published text and drawings as the basis for descriptions of species in his major work, Species Plantarum.

A mezzotint of Sir Hans Sloane - a print made from an engraved copper or steel plate. It was completed by J Faber, junior, 1729, after Sir G Kneller, 1716.

Image: Wellcome Collection gallery, via Wikimedia Commons.

This tree cotton specimen, Gossypium arboreum, is housed in the Sloane Herbarium.The shrub was included in Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum published in 1753.

Sloane died at the age of 93 in 1753. He had been keen for his collections to become available to the nation.

He made provision in his will that his collection ‘[...] may remain together and not be separated and that chiefly in and about the city of London, where I have acquired most of my estates and where they may by the great confluence of people be most used.’

He had organised for his collection to be offered to Parliament for £20,000 - a large amount of money but probably much less than its real worth. Money raised by a public lottery was used to purchase the collection, and the British Museum at Bloomsbury was founded. It opened six years after Sloane’s death.

Later, some of Sloane’s collection was moved to the Natural History Museum at South Kensington in the 1880s and to the British Library in 1973.

For the past 300 years, the collections have underpinned the work of a range of researchers and scientists.

Sloane’s specimens in our historical collections room which holds Sloane’s herbarium of dried, pressed specimensand his vegetable substances. The latter are mostly botanical objects, numbered and sealed in decorative glass boxes. Sloane carefully catalogued where they came from, who had sent them to him and what they were used for.

The Sloane Herbarium

The Sloane Herbarium is still housed in the Museum today. It contains an estimated 120,000 plant specimens bound into 265 volumes. It is the largest surviving botanical collection from the early modern period - about 1500-1800 - and contains plants collected in more than 70 countries and territories worldwide. Antarctica and Australasia are the only continents not represented.

The first seven volumes include the specimens collected during Sloane’s voyage to Jamaica, from 1687 to 1689.

The volumes are preserved in a purpose-built special collections room.

Sloane’s volumes are housed horizontally and the air is kept at a constant temperature and humidity. The room is designed to provide a place for scientists and historians to study the botanical resource.

Sloane’s other collections have had mixed fortunes since his death, with many mammal, bird and reptile specimens lost or destroyed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Museum is also home to a collection of Sloane’s books, manuscripts and correspondence.

It includes his handwritten accession registers, which put each specimen in context and give details of when, where and they were all acquired. These 19 volumes note the origin of specimens now in our Botany, Entomology, Mineralogy, Palaeontology, and Zoology collections.

Anyone can access information from the Sloane Herbarium using our online database. It remains an invaluable resource for both scientific and historical research.

Further information

Explore research into how our history and collections are connected to the transatlantic slave trade.

Visit the Sloane Herbarium online database.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media