A fly trapped in the sticky tentacles of a carnivorous sundew plant.

© Cathy Keifer/ Shutterstock

Carnivorous plants: the meat-eaters of the plant world

Kerry Lotzof

Carnivorous plants have developed a terrific array of weird and wonderful adaptations that help them flourish in nutrient-poor environments.

Enter the world of predatory plants – if you dare – and discover their inventive assortment of traps and sticky tricks.

What are carnivorous plants?

Carnivorous plants attract, trap and digest animals for the nutrients they contain. There are currently around 630 species of carnivorous plant known to science.

Although most meat-eating plants consume insects, larger plants are capable of digesting reptiles and small mammals. Smaller carnivorous plants specialise in single-celled organisms – such as bacteria and protozoa – and aquatic examples also eat crustaceans, mosquito larvae and small fish.

Carnivory is such an efficient adaptation that it’s evolved independently several times and occurs in unrelated plant families.

But while it’s great for a nutrient top-up, carnivory doesn’t replace the need for photosynthesis and root systems. Being carnivorous simply helps the plants make the most of all available resources.

Where do carnivorous plants live?

The habitats of carnivorous plants are varied but usually involve wet, low-nutrient sites including bogs, swamps, waterbodies, watercourses, forests and sandy or rocky sites. Carnivorous plants can be found on every continent except Antarctica and there are many species native to the UK including sundews, butterworts and bladderworts.

A common butterwort plant.

Image © Jerzy Strzelecki via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Attenborough’s pitcher plant.

Image © Dr Alastair Robinson via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

Common butterwort, Pinguicula vulgaris, grows throughout the UK on bogs, fens, wet heaths and moors. This plant employs sticky mucilage on the leaf surface to secure its prey. Purple blossoms appear atop a long stalk to help keep pollinators from their carnivorous leaves.

Found only near the summit of Mount Victoria on the island of Palawan in the Philippines, Attenborough’s pitcher plant, Nepenthes attenboroughii, is critically endangered. One of the largest of all carnivorous plants, it grows 1.5 metres tall and produces pitchers that are 30 centimetres in diameter – and it’s capable of digesting rodents.

How do carnivorous plants attract their prey?

Carnivorous plants use a variety of strategies to lure prey into their traps. Some produce strong-smelling nectar and have intense colouration that mimic flowers.

Others camouflage themselves seamlessly into their surroundings so that victims blunder into them. The intense colouration of trapping organs can give the impression that they are flowers when they are, in fact, ingeniously adapted leaves.

Carnivorous plants keep prey separate from useful pollinating insects by growing their real flowers at the end of long stalks, which blossom as far as possible from tempting and deadly digestive organs.

The trumpet pitchers of a Sarracenia plant are carnivorous leaves but are as bold and colourful as flowers.

© Jeanette Teare/ Shutterstock

How do carnivorous plants digest their food?

Most carnivorous plants produce digestive enzymes that dissolve their prey into a nutritious bug stew. Some provide an enticing home for symbiotic bacteria that they depend upon to break down their catch for them.

How do carnivorous plants capture their prey?

Though there are hundreds of species, each with unique adaptations, carnivorous plants can be classified into five groups based on their trapping methods – pitfall, adhesive, snap, snare and suction.

Pitfall traps

Pitfall-type traps are formed by a single leaf or rosettes forming tubular or pitcher-shaped traps. Prey is drawn to nectar at the pitcher rim. A slippery substance at the rim causes prey to lose its footing and slip into the base which is filled with digestive fluid.

Giant montane pitcher plant

A giant montane pitcher plant

Image from NepGrower via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

A summit rat, Rattus baluensis, feeding from the lid of a giant montane pitcher plant.

Image © Ch'ien Lee via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 2.5

Endemic to Borneo, the giant montane pitcher plant, Nepenthes rajah, is the largest carnivorous plant in the world. Its urn-shaped traps grow up to 41 centimetres tall with a pitcher capable of holding 3.5 litres of water. Scientists have observed vertebrates and small mammals in their digestive fluid.

Cobra plant

Darlingtonia californica is also known as the cobra plant.

Image © incidencematrix via Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

The cobra plant’s prey enters through a hole on the underside of its hooded leaves.

© Dr Fred Rumsey

Native to swamps in mountainous regions of the USA, the cobra plant, Darlingtonia californica, has hooded, tubular leaves that resemble a striking cobra. It’s the only species of its genus and does not produce its own digestive enzymes, relying on bacteria to break downs its prey.

Unusual alliances

Low’s pitcher plant

© Rustic Maveric/ Shutterstock

Low’s pitcher plant, Nepenthes Iowii, gathers nutrients in a way unlike most carnivorous plants. Its wide, toilet bowl-shaped pitchers are very sturdy and just the right size for a tree shrew to stand astride while feeding on the nectar at the lid. While feeding, shrews excrete directly into the pitcher, delivering useful, already-digested nutrients. Low’s pitcher plants grow on only a few mountainsides in Borneo.

A bat pitcher plant.

Image © BAZILE Vincent via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The bat pitcher plant, Nepenthes hemsleyana, has a fascinating alliance with woolly bats. Rather than producing nectar, it offers a convenient roosting site. Its pitchers have a prominent ridge that bats can cling to, and an enlarged opening that reflects their ultrasound calls through the dense vegetation of Borneo. In exchange, the plant receives all the nutrient-packed bat guano it needs to thrive.

Adhesive traps

Adhesive traps lure insects and other small prey with sweet, sticky droplets that look like nectar or dewdrops. Small insects are immobilised by the sticky slime and larger victims may struggle to break free, coating themselves further in the mucilage – death is usually indirect, via suffocation.

Some varieties of adhesive traps will actively curl their sticky tentacles around struggling victims.

Close up of a round-leaved sundew, Drosera rotundifolia.

Image © Petr Dlouhý via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

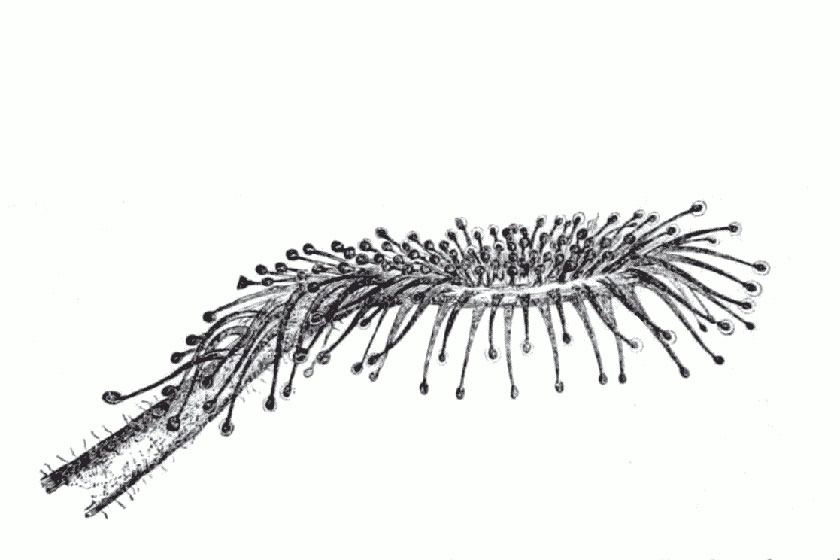

Illustration of Drosera rotundifolia from Charles Darwin’s monograph on insectivorous plants.

Sundew illustration via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

In 1875, Charles Darwin published a 400-page monograph on carnivorous plants that shook the scientific establishment. He found round-leaved sundews growing extensively in the heaths of Sussex and studied them closely.

Darwin fed sundew plants salts of ammonia, egg white and even small crumbs of cheese before describing their digestive systems and proving, unequivocally and for the first time, that carnivory exists in the plant world.

A species of sundew called Drosera intermedia.

© Dr Fred Rumsey

Snap traps

Some carnivorous plants catch their prey in snap-closing traps made of modified leaf blades.

Drawn by the promise of a flower, the insect or small reptile entering the trap stimulates sensitive trigger hairs. These send an electrophysiological impulse to snap the leaf blades shut and ensnare the visitor. Once a meal is secured, the leaf secretes a digestive fluid to resorb the animal protein.

Venus flytrap

Close up of a Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, showing its trigger hairs.

© Bjoern Wylezich/ Shutterstock

Venus flytraps are native to the subtropical wetlands of the US east coast. They can grow large enough to ensnare small lizards.

Waterwheel plant

The species Aldrovanda vesiculosa is commonly known as the waterwheel plant.

Image © Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The waterwheel plant, Aldrovanda vesiculosa, is an aquatic plant and the only underwater snap trap carnivore. Waterwheel plants grow worldwide, in nutrient-poor freshwater swamps. Their tiny traps grow up to one centimetre in length and capture prey including mosquito larvae, small fish and tadpoles.

Snare traps

Disguised as safe and delicious root structures, snare traps specialise in capturing single-celled organisms such as protozoans and ciliates, which they attract through chemicals. Organisms enter the snare trap through opening slits in tubular projections, and unidirectional hairs shepherd the tiny organisms into a digestive bladder.

Corkscrew plant

The corkscrew plant captures prey using subterranean traps.

Image © NoahElhardt via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The corkscrew plant, Genlisea violacea, is native to South America and develops small, purple blossoms. The image above shows the spiralling subterranean traps. Inside are tiny hairs that force prey into the plant’s equivalent of a stomach.

Parrot pitcher plant

Parrot pitcher plants are a combination of snare and pitfall traps.

Image © Michal Klajban via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Native to North America, parrot pitcher plants, Sarracenia psittacina, have tubular leaves that lay flat along the ground. They offer a welcoming hidey-hole and chemical lure for their soil-dwelling prey, which are then forced toward the digestive tract with unidirectional hairs. They have a similar form to other pitcher plants and are technically a combination of snare and pitfall traps.

Suction traps

Suction traps are a feature of many aquatic carnivorous plants. Prey animals are drawn to lures at the trap entrance that mimic food or shelter. A prey’s proximity to the trap entrance triggers a valve trapdoor to open into a hollow bladder, creating suction that then flushes the prey inside. The trapdoor then quickly swings shut and the entrance is sealed with slime to prevent escape.

Aquatic bladderworts

Lesser bladderwort, Utricularia minor.

© Dr Fred Rumsey

Aquatic bladderworts are rootless aquatic plants that grow in fresh water all over the world.

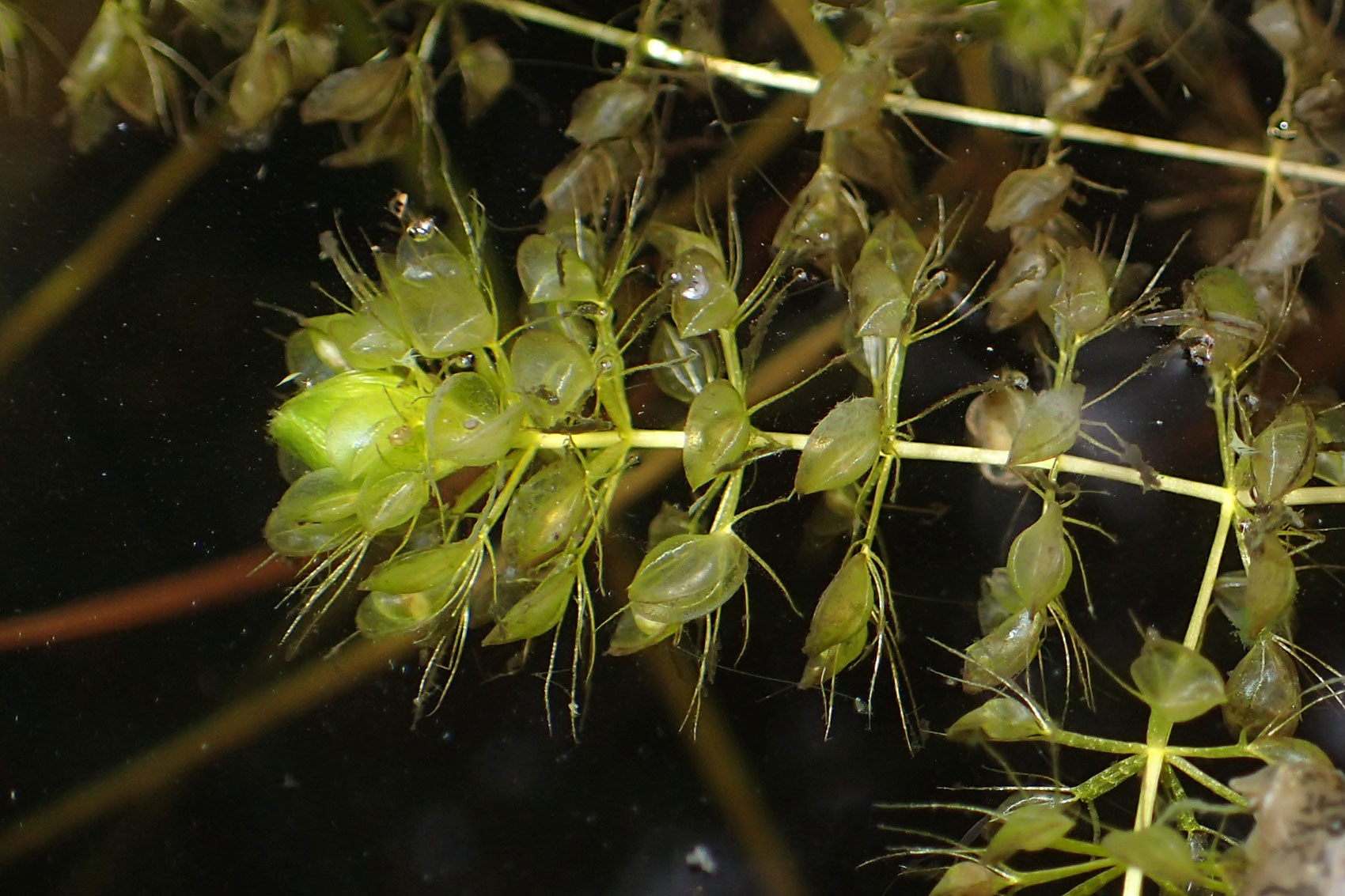

Common bladderwort, Ultricularia vulgaris.

© JIANG TIANMU/ Shutterstock

A clump of aquatic bladderwort, Utricularia vulgaris, from the UK with transparent bladder traps. The filament-like shoots of aquatic bladderworts mimic algal threads that attract food for small crustaceans.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media