Imagine you are an archaeologist excavating at a new building site in East London, the location of an ancient cemetery. Deep down you uncover bones that look old. You recover a full skull with teeth, and most of the bones of the body, missing a few smaller vertebrae and toes.

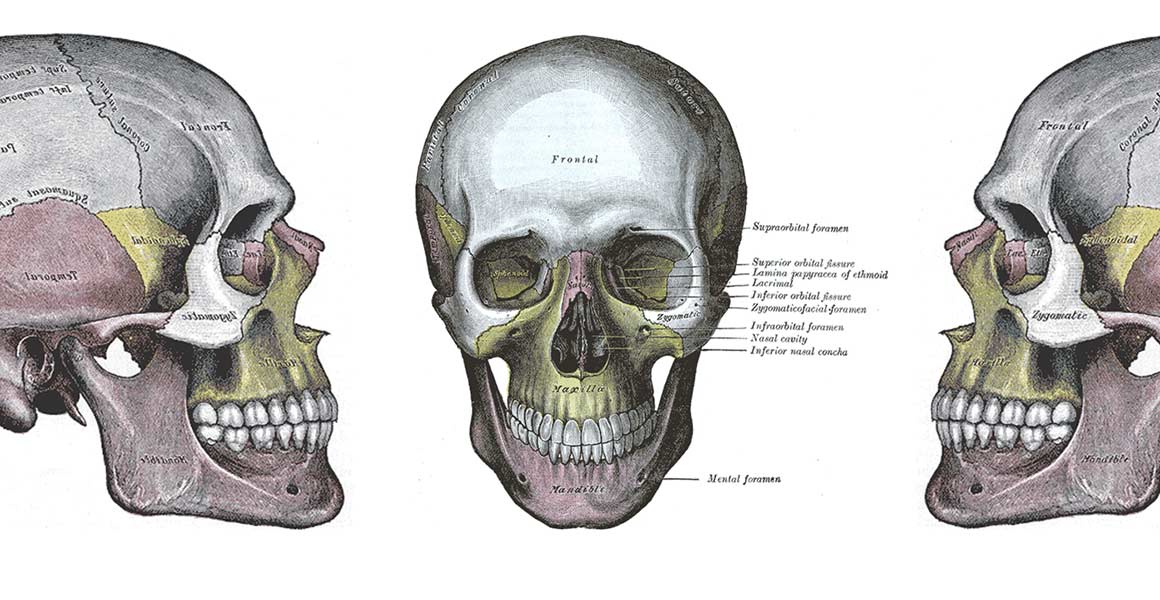

Drawings of the human skull from Gray’s Anatomy (1858)

What can you find out about the person you’ve found? You can actually learn a lot just by having a closer look at their bones and teeth - such as who they were, what their life was like, and sometimes even how they died.

Who have I found?

The first thing you might want to know is the sex of the person. There are two parts of the body most useful for determining sex: the pelvis and the skull.

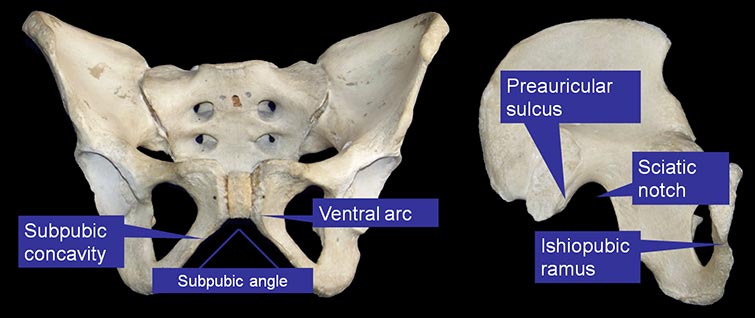

As you might expect, females have wider pelvises, which are necessary for childbirth. But there are six other parts of the pelvis anthropologists look at to determine sex.

The features of a female pelvis

If the person was female, you will see the following features:

- a wider subpubic angle

- a broader sciatic notch

- a subpubic concavity, which is absent or shallower in males

- a sharp ridge down the ischiopubic ramus, which is flat and blunt in males

- a preauricular sulcus (a notch or depression), which is more commonly seen in females

- a ventral arc, absent in males

Often, however, only the skull of an individual is found. Fortunately, there are a lot of characteristics on the skull that can be used to determine sex.

Next, how old was the person when they died? As with sex, both the skull and the bones hold clues to this question.

The teeth are very useful for determining the age of a child. The stages at which different teeth erupt from the gums are well known, and can be used to tell a child’s age to the year. But once all the adult teeth are fully developed, age is harder to determine. Adult teeth are worn down by chewing, and sometimes the amount a skeleton’s teeth are worn down can be used to estimate age. However, factors like a rough diet can mean an inaccurate age estimate.

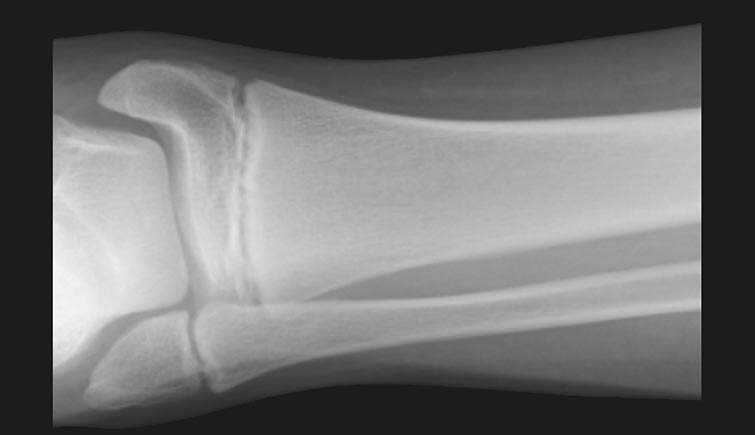

X-ray of a child showing unfused leg bones near the ankle

You might face a similar problem when looking at the skeleton. Until the age of about 30, your bones are still growing, and the ends of the shafts are fusing to short bone caps called epiphyses. Different epiphyses fuse at different stages of growth, so by looking at these an accurate age can be determined.

Just like the teeth, however, once adulthood sets in age is determined by wear and tear instead of growth. In particular, the pelvic bones and ends of certain ribs erode and deteriorate over time. However, these bones changes are quite slow, so the age estimates are less precise than for younger people. They are often categorised as either ‘young’ (20-35 years), ‘middle’ (35-50 years) or ‘old’ (50+ years).

Part of the pelvis showing differences between a young (left) and old (right) person

What can I learn about their life?

Perhaps sadly, one of the easiest things to tell about someone’s life from their skeleton is what diseases they had. Markers of disease in the teeth and bones of an individual can say something about their life, and looking by at patterns of disease across whole groups of people, anthropologists can learn about trends in health and hygiene across time.

For example, ‘dental attrition’, the wearing down of teeth, was often worse during the Roman and Medieval periods in Britain. This is because food was coarse, and grit from stones used to grind wheat would get into the flour and erode people’s teeth. On top of that, people often ‘brushed’ their teeth with old rags and homemade tooth powders including chalk, salt, charcoal or even crushed bricks.

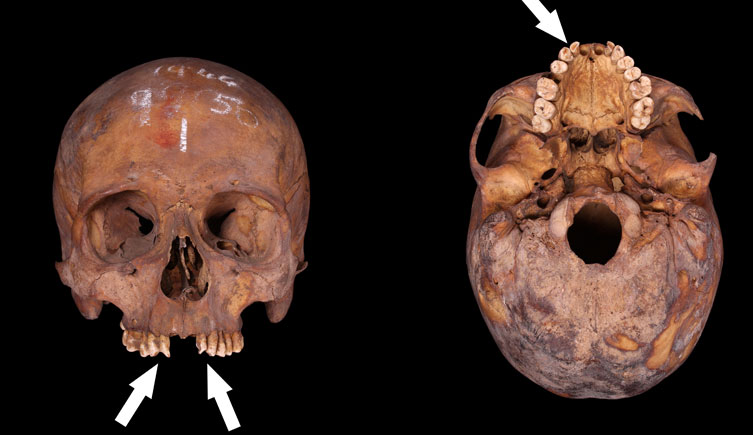

The teeth indicated by arrows are rounded by repeated holding of a pipe

Some attrition forms in patterns on the teeth, and these can be used to tell something about the person’s work or habits. For example, certain teeth with more attrition can suggest chewing leather to soften it, holding twine during basket weaving, or even smoking a pipe.

In addition to dental attrition, many other kinds of dental diseases familiar today are regularly found in historic skeletons. Issues you might spot include:

- caries - commonly known as cavities, caries are caused by bacteria that feeds off of the food debris and sugar that is lodged in our teeth and gums. They became much more widespread in the post-medieval period as production and consumption of refined sugar skyrocketed.

- dental calculus (plaque) - calculus forms when minerals in saliva cause bacteria to solidify on our teeth. Brushing and cleaning removes calculus and prevents build-up.

Roman skull showing extreme calculus build-up

- tooth loss - both cavities and calculus can lead to tooth loss. Cavities can cause the inner pulp of the tooth to become infected, creating an abscess that eats away at the bone, eventually making the tooth fall out. Calculus build-up inflames the gums, leading to bone loss in the area and the eventual loss of the tooth.

Two skulls showing dental abscesses

In the video below, osteologist Elissa Menzel demonstrates how to spot signs of dental decay.

Evidence of disease is also evident in many parts of the skeleton. One of the most obvious and disfiguring diseases was syphilis.

Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by a bacterium known as Treponema pallidum, and it only became widespread in Europe in the post-medieval period. It is spread through sexual contact and can be passed on from mother to baby. The disease is thankfully now rare, and readily treatable with antibiotics.

Five remains in the Museum’s collection show signs of the final, severe stage of the disease. In the video below, osteologist Linzi Harvey shows how you can spot the tell-tale signs of this disease.

Skeletons across the ages display degenerative bone changes associated with age and wear, and on your skeleton you might find signs of the following diseases:

- osteoarthritis is when cartilage wears away and the bones rub together, causing erosion and polishing of the bones, and sometimes new bone growth.

- rheumatoid arthritis is a disease that causes painful, swollen joints, which can lead to bone remodelling. The first known case in the UK is recorded from remains in a medieval abbey.

- ankylosing spondylitis is when the spine is inflamed, leaving characteristic bone markers on the vertebrae.

- gout is caused by increased uric acid in the blood, which can crystallize and be deposited in joints, in extreme cases causing erosion of the joint surfaces. It is commonly associated with a diet high in red meat, and so has been associated with the rich.

- diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis is when the ligaments of the spine become bone and fuse together. It particularly affects older males and can be associated with type II diabetes.

Spine showing signs of fusing as a result of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

How did they die?

Although we can tell a lot about a person from their bones, determining how they died can be difficult.

It can be tempting to see signs of trauma on a skeleton as evidence of a violent death, but most fractures are not fatal. There are 33 individuals with signs of trauma in the London collection, and of these only two show possible evidence of fatal blows.

When trauma occurs before death, healing can be seen around the edges of the wound. ‘Perimortem’ trauma from around the time of death however shows no signs of healing.

Skull dredged from the Thames displaying unhealed perimortem trauma

You might find three types of trauma on the skeleton:

- fractures result from stresses on the bone, causing them to crack and break. Fourteen individuals in the collection show evidence of this kind of trauma, all healed to some extent. The majority were on the skull, but one prehistoric individual has a fracture in a vertebra, probably as the result of a fall. Most of the fractures caused by direct impact identified in the Museum’s London collection are on the nose and face.

- sharp force trauma is when a sharp object comes into contact with the bone, such as a blade or cut glass. Three individuals in the collection show evidence of healed sharp force trauma.

- blunt force trauma is caused by impact from a blunt object. One individual in the collection from London shows evidence of blunt force trauma.

In the video below, osteologist Elissa Menzel demonstrates how to spot signs of trauma.

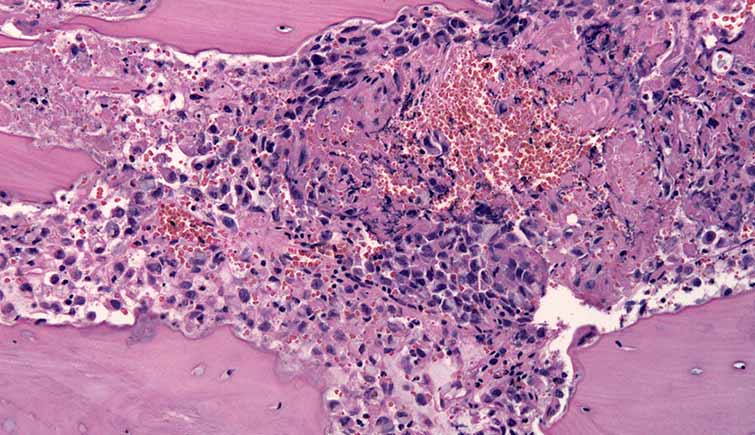

Not all deaths are so violent. Signs have been found in medieval remains from Europe that point to a disease considered to be modern: cancer. Cancer often affects the bone when it metastasises: when it spreads from the soft tissue to the bone, a condition that almost certainly would have been fatal in the past.

Prostate cancer that has spread to the bone

Analysing the bones and teeth of individuals can give us insights into the details of their lives, such as whether they smoked a pipe or had a rich diet. But by looking at human remains found across London, researchers can build up a picture of life in the city throughout the ages, from Romans with terrible dental hygiene to post-medieval people struggling with the rising tide of syphilis.

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media