The quick answer to this is no. If you read my post on who visits our collections and why? you will see that we host visits to the microfossil collections from local amateur groups, artists and very occasionally historians. One of my visitors last week, artist Jennifer Mitchell seemed genuinely surprised that we so readily open the door to visitors who are not scientists in professional positions, or university students. This post investigates how she found us and whether we do enough to encourage visits from non-scientists.

Haeckel and the radiolarians

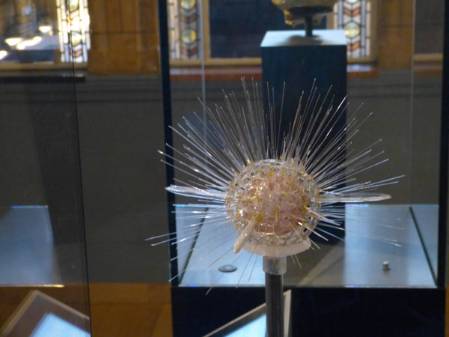

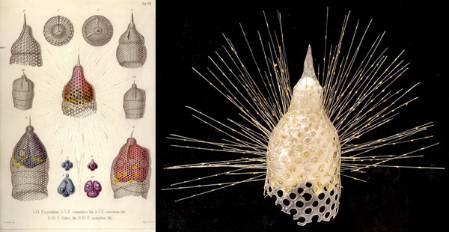

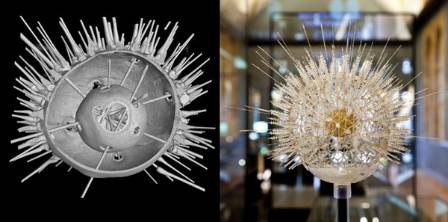

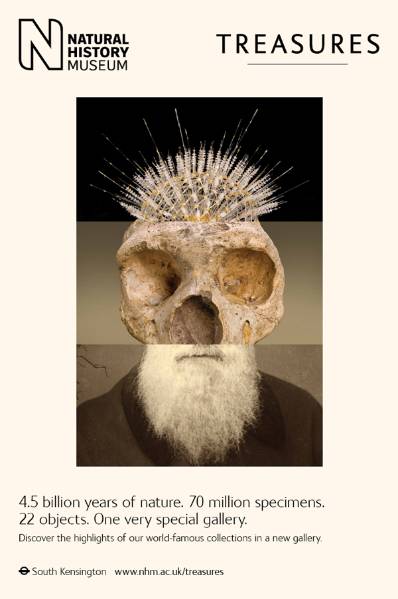

Jennifer was enquiring about the historical collections of famous evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) and in particular material collected on the H.M.S. Challenger Expedition of 1872-1876. Haeckel published some amazing illustrations of marine life including illustrations of the microscopic radiolarians. Haeckel's work inspired the famous father and son Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka to create glass models of radiolarians, examples of which can been seen in our Treasures Gallery. Jennifer wanted to see the original material from which Haeckel's illustrations were created.

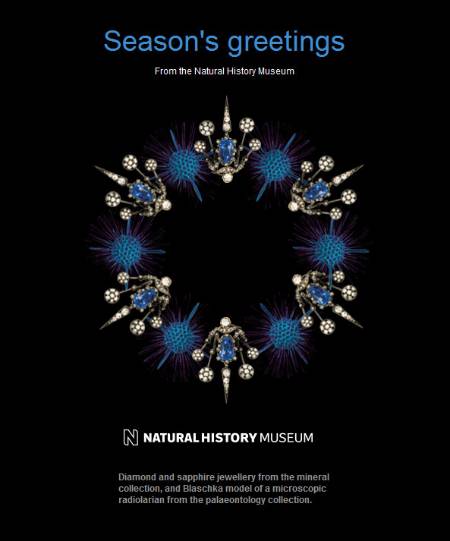

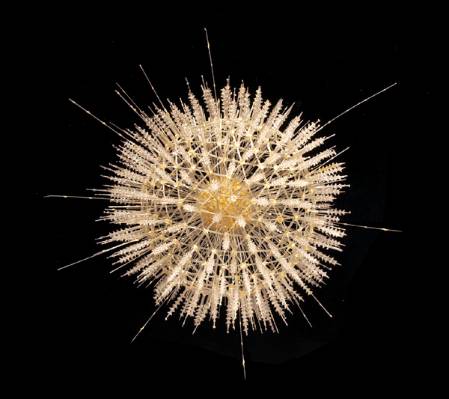

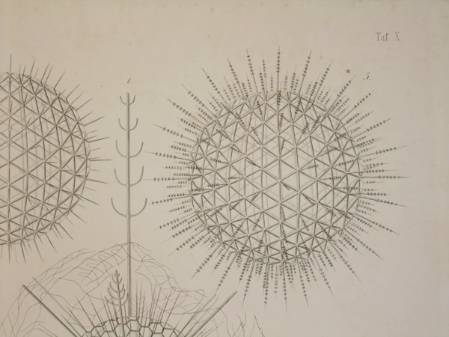

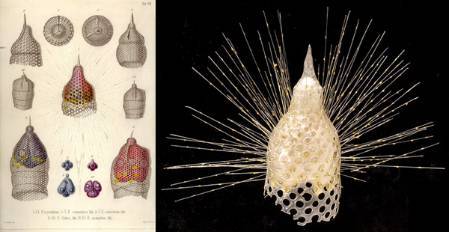

Some artwork from a monograph published in 1862 by Ernst Haeckel on the radiolarians, alongside a Blaschka glass model of a radiolarian inspired by Haeckel's work and displayed (on rotation) in our Treasures Gallery.

Some artwork from a monograph published in 1862 by Ernst Haeckel on the radiolarians, alongside a Blaschka glass model of a radiolarian inspired by Haeckel's work and displayed (on rotation) in our Treasures Gallery.

I was interested to hear how Jennifer knew to contact me to arrange access. Her initial enquiry came via the Museum Archives web pages. The archivist responded that Jennifer needed to contact my colleague Miranda Lowe in Life Sciences and Miranda passed the enquiry to me when she realised that it related to our microfossil collections.

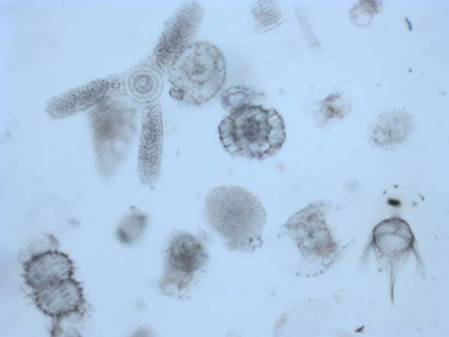

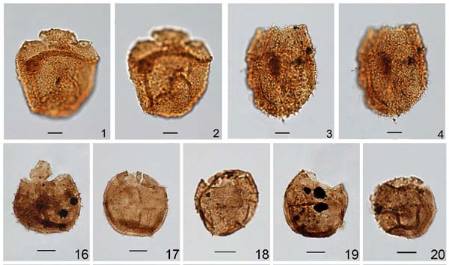

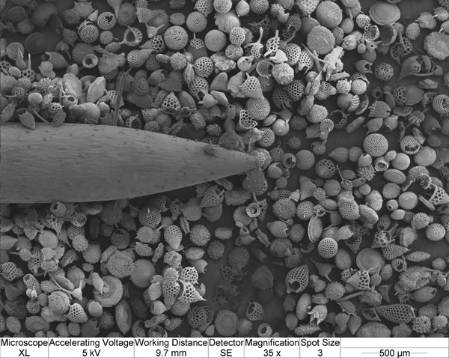

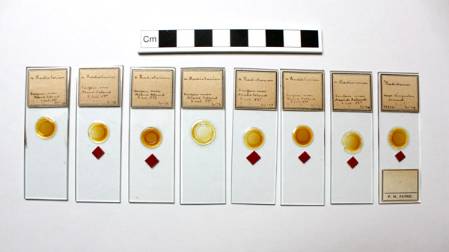

One of the Ernst Haeckel slides that Jennifer Mitchell viewed during her visit. Haeckel created sets of slides that he sold to various museums including the British Museum of Natural History.

Less than 5% of our enquiries about the microfossil collections come via the Museum website, where there is a link to a general enquiries e-mail. This general email then gets forwarded to the relevant curator or researcher for them to deal with. The vast majority of the enquiries I get are direct from people that have had some prior connection with me or the Museum.

Does this mean that people find it difficult to know who to contact and are therefore put off enquiring about our collections? Jennifer's example suggests that this might be the case, although she did finally find the relevant person via several emails.

Let's digitise

Are we doing enough to let people know about our behind the scenes collections? Our website gives some details but the vast majority of our microfossil collections are not findable via a search facility on our site because they are not computer registered. Mainly visitors know of our collections because of the publications that cite them.

The Museum is engaging in a major digitisation project aimed at digitising 20 million of our specimens in the next 5 years. This will almost certainly help, but my experience of delivering collections information to the web is that you still need to keep telling the relevant audiences that you can search for specimens on our site by advertising the URL.

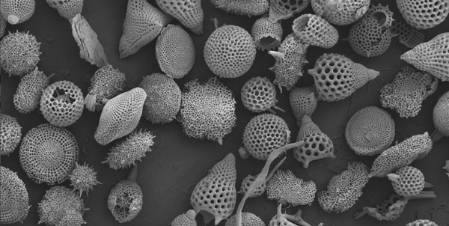

This is what Haeckel saw down the microscope. It's amazing to see the material he used to create the illustrations in his famous monographs. Even with modern microscopes the depth of field issue means that the specimens are never all in focus at once hence the blurry nature of this image.

Would we get more enquiries if we more proactively advertised contact details and that we facilitate access to our behind the scenes collections to a wider audience by appointment? Almost certainly we would. I see it as an important part of my role to make people aware that our collections are here to be used by whoever wants to use them. This was the over-riding reason for me in starting this blog.

However, hosting an increased number of visits and maintaining visitor facilities is a major drain on resources such as staff time. I firmly believe that it is our duty to make these collections available to everyone, but it does come at a cost.

A wider reach with limited resources?

Some of my colleagues in charge of popular and high profile parts of our collection host a constant string of visitors, so advertising to a wider audience would not be appropriate because resources are not available to cope with increased visitor numbers. I would argue that the Museum galleries allow access to a wider audience for these types of collection (e.g. dinosaurs, meteorites, early humans, mammoths).

For the microfossil collections, where we have virtually nothing on display, it is a balancing act between advertising to promote access and encouraging so many visitors that we don't have the resources to deal with them.

So our collections are available to a wider audience beyond professional scientists and students, but I would argue that we could do more to advertise our microfossil collection to all audiences by appointment. Jennifer suggested 'to be able to contact the curator or appropriate person directly from the website and let them deal with the request directly would be more efficient for everyone especially the curators'.

It will be really interesting to see how enquiries access is handled when the current project to revamp our Museum website is finished. I'd also love to hear any opinions on access to behind the scenes collections, particularly if you have ever tried to find out about and arrange a visit to our microfossil collections.