My work diary of last week, in which members of the public put a valuable part of the collection at risk with their smart phones, tiny floating snails cause a flurry of visitors and microfossils are mentioned on the Test Match Special cricket commentary(!) in a varied week for the curator of micropalaeontology.

Monday

First up is a trip across the Museum to the Nature Live Studio with some delicate specimens that will be the subject of my two public talks later in the day. We can't move large items across the Museum during opening hours and, with the galleries filled with summer visitors, this is more than sensible at present.

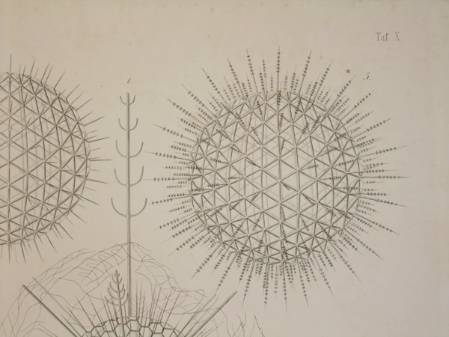

In the Nature Live Studio with host Tom Simpson - a CT-scan of a Blaschka glass radiolarian model on the screen.

All of the specimens in my care bar the one in the Treasures Gallery are housed behind the scenes, so regular visitors might not even know that we have microfossil collections. A previous head of palaeontology collections calculated that we have as few as 0.001 per cent of our fossil collections on display.

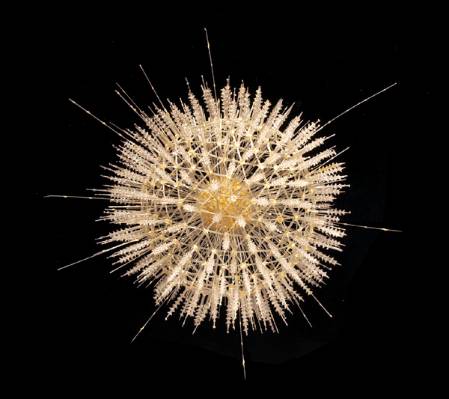

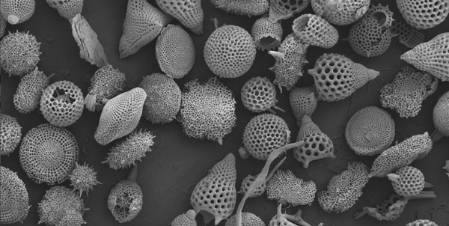

If you haven't been to one yet, the Nature Live events are a great way to bring these parts of our collections out for the public and allow us to talk about our science. The incredibly delicate and unique Blaschka Glass models of radiolarian microfossils are always a big hit, but we have to ask a smart phone-brandishing throng of children and their parents to move away from the specimens after the first show as a mother leans over the barrier and takes a picture on her phone from right above the specimen. We add two extra barriers for the second show!

Tuesday

I've had an enquiry from The Geological Magazine asking me to review a book that I have almost finished reading. I have to think carefully about saying yes or no. Receiving a free copy is the usual bonus for undertaking these tasks but, as I have a copy already, dedicating a lot of time to a review does not seem so appealing.

I decide that I shall send the extra copy to my student in Malaysia but I think I will wait until after she has finished writing up her MSc thesis. Her first chapter arrives today for comment as do some proofs for a book chapter on microfossil models that I have written. Much of the day is spent checking these and providing additional information requested by the editors of the book. It will be about the history of study of microfossils and will have an image of one of our microscope slides on the cover.

Wednesday

The galleries are packed with summer visitors but it is relatively quiet behind the scenes with many staff on annual leave, away on study trips, conferences or fieldwork.

This quieter period is a good time to catch up on some of the documentation backlog so today I finish documenting a new donation, continue to work on a large dataset relating to specimens from the Challenger Collection, and register 30 Former BP Microfossil Collection specimens that are due to go out on loan to the USA.

I spent my first 6 years at the Museum on a temporary contract curating the Former BP Microfossil Collection so it is always satisfying to see it being used by scientists. We have big plans for this collection in the future. However, I feel that I will need to do more than wait for a rare quiet day if I am to meet my part of the databasing targets set by the Museum. We plan to have details of 20 million of our specimens on our website within 5 years.

Thursday

An enquiry has come in this week about our heteropod collection. These are tiny planktonic gastropods, or literally floating snails. They are of great interest to scientists looking to quantify the effects of ocean acidification because they secrete their shells of calcium carbonate directly from the seawater that they lived in.

Measurement of carbon and oxygen isotopes from fossil examples can give details of the composition of ancient oceans and help to quantify changes over time. I mention the enquiry to staff in the Life Sciences Department and three visitors arrive to look at our collection within a day, including two from the British Antarctic Survey looking to develop projects on ocean acidification.

Friday

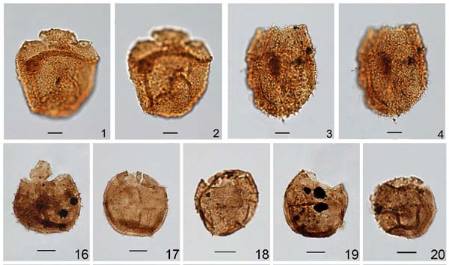

It is back to documentation again, a task I often save for days when the cricket is on. I am amazed when I hear dinoflagellates mentioned during the Test Match Special commentary. Dinoflagellates are protists that are a major consituent of modern and fossil plankton. We have thousands of glass slides of them here at the Museum within the micropalaeontology collections.

New species of Australian Jurassic dinoflagellate Meiogonyaulax straussii (1-4) and Valvaeodinium cookii (16-20) published by Mantle and Riding (2012). Images courtesy of Dr Jim Riding, British Geological Survey.

New species of Australian Jurassic dinoflagellate Meiogonyaulax straussii (1-4) and Valvaeodinium cookii (16-20) published by Mantle and Riding (2012). Images courtesy of Dr Jim Riding, British Geological Survey.

A regular visitor to our collections who works at the British Geological Survey in Nottingham has described two new species of Jurassic microfossil from the NW Shelf of Australia and named them strausii and cookii after the former and current England cricket captains and Ashes-winning opening batsmen. It causes much merriment in the Museum microfossil team as another former England Captain, Michael Vaughan, remarks on the radio that they look rather like omelettes.

Cricket is the theme for today as I attend a lunchtime retirement party for a former cricketing colleague at the Science Museum next door. I leave a colleague to take a visitor to lunch but come back to find that he has gone home sick and the visitor is still here with a list of requests that account for the rest of the day...