A couple of weeks ago we processed a loan to Prof. Dil Joseph and his team at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. They have developed a new method for imaging microfossils under a light microscope called Virtual Reflected Light Microscopy (VRLM). As well as being a novel use for some of our historical residue collections, this potentially provides an interactive method for viewing our collections in 3-D on-line and could greatly aid future users of our collections.

Cindy Wong, Adam Harrison and Dr Dileepan Joseph of the University of Alberta (photo courtesy of Ryan Heise, Communications Officer, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Alberta)

VLRM involves photographing microfossils under many different light conditions and from many different angles so that 3-D images can be built up. The team has also developed software to deliver these images to the web via an interactive interface that allows users to digitally manipulate specimens. A demo of VLRM can be found on-line and 3-D images can be obtained with the help of red-cyan glasses.

In normal circumstances we would make 2 dimensional images of specimens with either a light microscope or with a scanning electron microscope. These would be sent to enquirers about the collections. If possible, scientists would prefer to visit the Museum as they would normally need to manipulate specimens to see features that would not always be visible from 2 dimensional images. VLRM potentially recreates that visitor interaction with the specimens remotely on-line.

Part of the ocean bottom microfossil residue collection housed in the Department of Palaeontology.

The team have borrowed some of our most significant microfossil residues to test their system and develop future applications. These residues come mainly from the H.M.S. Challenger Collection. The Challenger Expedition of 1872-1876 was the first oceanographic voyage. Prior to this, the ocean bottom was completely unexplored so these residues represent a 'first ever glimpse' of the bottom of the worlds oceans.

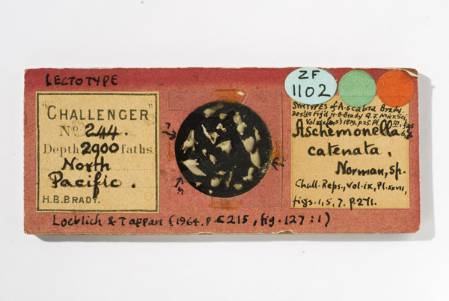

All of the organisms discovered during this first dredging of the ocean bottoms, including the microfossils, were described resulting in many new species being found. The foraminiferal type specimens of many of these species are housed here in the Museum and are frequently consulted by visitors. When a new species is described, a type specimen must be designated and deposited in a recognised museum so that future workers can consult them if neccessary.

A type slide from the Challenger Foraminifera Collection. It is 7.5cm long.

As the research is being done in North America, it was topical that we also loaned a residue from the Second Albatross Cruise of 1882. The Albatross was reportedly one of the the first vessels built for oceanographic studies and made its maiden voyage from Washington.

Dil Joseph's team in Edmonton have already published on computer aided recognition of foraminifera. It will be very interesting to see how historically significant materials from our collections play a part in future research on this subject. Work on Virtual Reflected Light Microscopy certainly looks to revolutionise how data on microfossil collections will be shared and how we make our collections available in the future.

Special thanks to Lil Stevens who processed this loan. She has now joined the full time curatorial staff and is helping out with micropalaeontology curation.