The Museum runs an After Hours event called Crime Scene Live that in February featured micropalaeontology curator Steve Stukins.

Micropalaeontological evidence is increasingly being used to solve major crimes. Read on to find out about Steve’s involvement in Crime Scene Live, how our collections could help forensic studies and how our co-worker Haydon Bailey gathered some of the evidence that was key to convicting Soham murderer Ian Huntley.

Botanical or microfossil evidence?

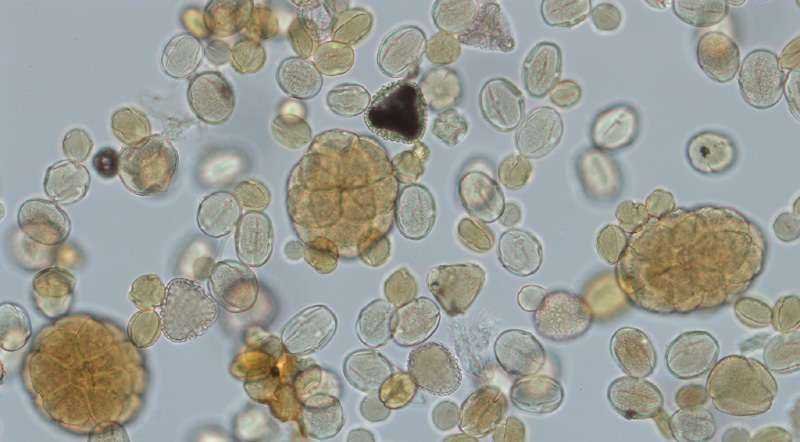

The following image is of modern pollen, so could be described as botanical rather than micropalaeontological evidence.

A variety of modern pollen types similar to the ones investigated at the Crime Scene Live event.

As I mentioned in my post What is micropalaeontology?, distinguishing when something is old enough to become a fossil is difficult, particularly when some modern species are present in the fossil record. The Museum's microfossil collections contain modern species, particularly our recently acquired modern pollen and spores collection, and this collection has enormous potential as a reference for forensic investigations.

What can microfossil evidence tell us?

Because organisms that produce microfossils are present in a wide range of modern and ancient environments and can be recovered from very small samples, they can provide a lot of useful information. Mud or sand recovered from boots or clothing can show where the wearer has been and even the pollen content of cocaine can provide evidence of its origin or where it was mixed.

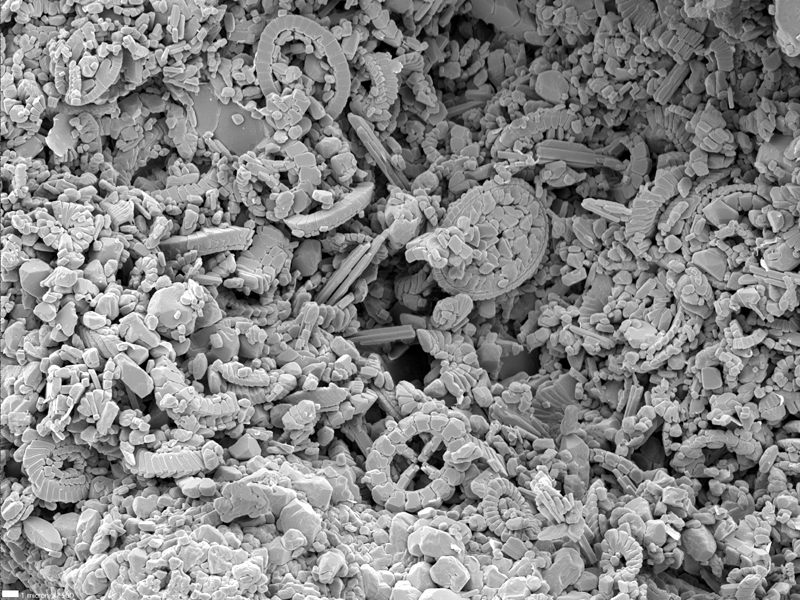

A scanning electron microscope image of British chalk showing nanofossils.

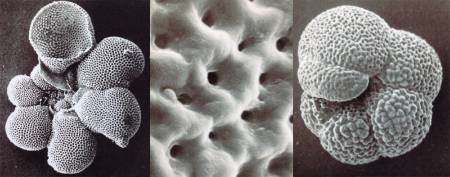

These details can relate a suspect to a crime scene, relate items to a suspect/victim or crime scene and prove/disprove alibis. Evidence can also show cause of death, for example, diatoms or freshwater algae present in bone marrow can indicate drowning.

Microfossil evidence helps solve the Soham murders

Haydon Bailey, who is working temporarily at the Museum on a project studying our former BP Microfossil Collection, provided some key evidence that convicted Ian Huntley of the Soham murders.

Haydon identified chalk nanofossils on and inside Huntley’s car that were common to the track leading up to the site 30 miles from Soham where the bodies had been dumped. For details about all the scientific evidence used, this article on the Science of the Soham murders is an interesting read.

Members of the public participating in Crime Scene Live activities.

Senior Micropalaeontology Curator Steve Stukins writes about Crime Scene Live at the Museum:

"This special public event gives the audience a chance to become a crime scene investigator for the evening using techniques employed by scientists here at the Museum. People are often surprised that the Museum is involved in forensic work, especially using entomology (insects), botany (plants) and anthropology (analysis of human remains). Crime Scene Live uses all of these disciplines and forms them into an engaging scenario for the visitors to get involved in.

Palynology, in most cases pollen, is used quite often in forensics. As pollen is extremely small, abundant and diverse in many environments it can be used to help determine the location of a crime and whether a victim/perpetrator has been in a particular place by understanding the specific pollen signature of the plants in an area.

Our jobs as forensic detectives in the Crime Scene Live Event were to determine where a smuggler had been killed, for how long he had been dead and the legitimacy of the protected animals he was thought to be smuggling. I’ll be giving away no more secrets about the evening, other to say that it was a great pleasure to be involved in a thoroughly enjoyable event and the feedback from the visitors was superb."

So if you fancy a bit of murder/mystery then why not come and help micropalaeontology curator Steve Stukins solve the Case of the Murdered Smuggler on 1 May or in October. Details of other Crime Scene Live events scheduled for this year can be found here.