Film crews are not an uncommon sight behind the scenes at the Natural History Museum but they have never come to see me ... until recently, that is.

Filming takes place in the Palaeontology Department regularly for documentaries, with staff interviewed or specimens brought out from their cabinets for a few minutes of fame. Usually the film crews want large vertebrates like dinosaurs or early human fossils, and one or two members of staff are well known for regular appearances in the media. For example, an episode of the BBC TV show New Tricks was filmed after hours last November and recently the department was featured in the BBC Documentary Museum of Life.

At the time I was disappointed that no aspect of micropalaeontology was featured in the BBC’s programme. So it was a pleasant surprise when I was asked to provide some specimens for a Korean film crew from EBS (Educational Broadcasting System) who were making a documentary on the early evolution of life called "The Secret Lives". They wanted to know about the earliest armoured fishes, the arandaspids.

These early fish were probably poor swimmers, scrabbling around on the bottom of the shallow sea, filtering for food. They play an important role in helping us to understand the early evolution of vertebrates. For further details including a picture of a whole arandaspid fish see:

http://accessscience.com/studycenter.aspx?main=7&questionID=5120

http://tolweb.org/Arandaspida/16907

Perhaps my most important fossil discovery was some fragments of the arandaspid Sacabambaspis in a consultancy sample sent to me from Oman in 2005. I wasn’t expecting to find fish and certainly not anything as significant as this. Luckily for me a university colleague had a large grant to study them so he funded a trip there in November 2006.

Wadi Daiqa, Oman

Because they are so small we were not expecting to see any "in the field" and were expecting to have to take back rocks to the Museum to dissolve and analyse. However, on the final day of our trip I saw by my foot a specimen with some tiny fish fragments.

The specimens themselves appear on the surface of some rocks as tiny black specks so I was amazed that I managed to see them (especially as I was told on my return that I would need glasses for reading!).

As a result of my find we went back in 2007 to collect some more samples. The image below suggests that they should be easy to spot. However, this is the very best specimen discovered after days of searching and the fragments are much larger than the original find.

The film crew first wanted a close up of the rock...

Close up of the surface of the rock being filmed. Impoverished curators use a one pence piece for scale.

Filming a close up of the arandaspid fish fragment rock in the Palaeontology Imaging Suite.

Then they wanted me to talk about its significance and say what it tells us about early fishes and their habitat.

The Oman discoveries showed that the fish were present all around the margins of the ancient continent of Gondwana and not just in the southern regions as had previously been shown by the findings from South America and Australia. In the Ordovician period about 450 million years ago, Gondwana was an amalgamation of what we currently know as Africa, South America and Australia with some parts of China and the Middle East.

Rocks from similar geological settings have produced similar fish fossils from Argentina, Bolivia and Australia so we know that this particular type of fish lived in shallow waters on the continental margins of Gondwana.

After this they wanted to film a close up of some arandaspid scales and plates on a computer screen. The filming took place in the Palaeontology Department’s imaging suite where we used a Leica microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera to provide a close up of some of the specimens that we found.

Zeiss Axiocam set up in the Palaeontology Imaging Suite.

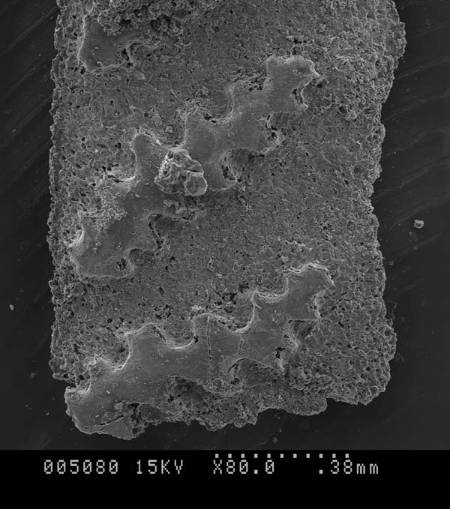

Here I was able to show a close up of the rock on the computer and to show some features of the microscopic fragments that were inside it. I have already photographed some fragments by scanning electron microscope (SEM) so I was also able to show some of these to illustrate the close up features of some arandaspid fish scales. The “oak leaf”-like tubercles are typical of this type of fish.

Scanning electron microscope image of a scale of Sacabambaspis showing oak-leaf tubercles. The scale on the bottom is 0.38mm so the width of the scale is less than 1mm.

Sadly, I’m not sure I’ll ever see the final product as I don’t think our TV gets EBS. However, I am happy to play a small part in researching into some of the earliest vertebrates to have lived on our planet.