One of my curatorial predecessors Randolf Kirkpatrick (1863-1950) thought that larger benthic foraminifera (LBFs) were so important that he published a theory that they were vital to the formation of all rocks on earth. Our collection of LBFs has received relatively little attention over the 20 years I have been at the Museum, but recently it has been the most viewed part of the microfossil collection.

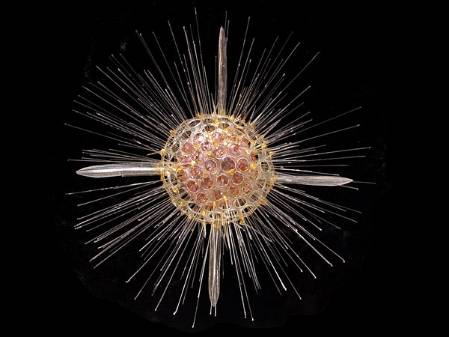

Some images of larger benthic foraminifera (LBF) taken by Antonino Briguglio, a recent SYNTHESYS-funded visitor to our collections. The images represent specimens roughly the size of a small fingerprint.

Traditionally LBFs have been difficult to study but new techniques, particularly CT scanning, are changing this perception. This post tells the story of Kirkpatrick and explains how the collection is currently being used for studies in stratigraphy, oil exploration, past climates and biodiversity hot spots.

Larger benthic foraminifera (LBF)

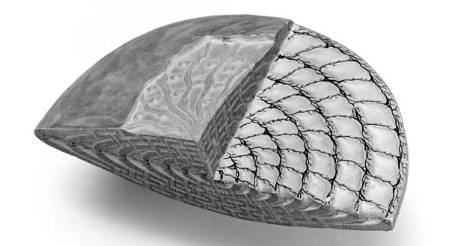

Larger benthic foraminifera are classified as microfossils because they were produced by a single celled organism, but they can reach a size of several centimetres. Their study is difficult because it usually relies on destructive techniques such as thin sectioning to make precise identifications. My first line manager at the Museum Richard Hodgkinson was an expert at producing these thin sections. He described the technique of cutting the specimens exactly through the centre as an art rather than science. Sadly there are very few people in the world skilled enough to make these sections, but thankfully the Museum collection is packed with LBF thin sections available for study.

Randolf Kirkpatrick's Nummulosphere

Randolf Kirkpatrick was Assistant Keeper of Lower Invertebrates in the Zoology Department of the British Museum (Natural History), and worked at the Museum from 1886 to his retirement in 1927. He published on sponges but is most famous for his series of four books entitled The Nummulosphere that he had to pay to publish himself because his ideas were so unusual. In the Introduction to part four he writes:

'Fourteen years have passed since the publication of Part III of the Nummulosphere studies, but the scientific world has entirely ignored the work to its own real and serious loss... I think it not amiss to call attention to the financial aspect. Since its beginning in 1908, this research has cost me much over £2000, all paid out of a modest salary and pension, and certainly by a cheerful giver.'

Kirkpatrick developed a theory that at one stage Earth was covered with water and LBFs of the genus Nummulites accumulated into a layer he called 'The Nummulosphere'. He went on to suggest that all rocks we see now were subsequently derived from this nummulosphaeric layer and he figured examples in his books of supposed nummulitic textures he had seen in granites and even meteorites.

I think that Kirkpatrick would be very interested to hear that scientists are looking for evidence of life on Mars and that meteorites may hold the key to this. Obviously the evidence of life, if it arrives, is almost certainly not going to be a LBF. However, I think that if he were alive today, Kirkpatrick would be very interested to hear of the renewed interest in our LBF collection and that his earlier publications on sponges have also received renewed interest. These publications had been largely ignored because of his later publications of the Nummulosphere theory.

Image of palm-sized model of a nummulite made in plaster of Paris based on an original illustration by Zittel (1876), showing strands of protoplasm colonising its complex shell.

Find out more about Kirkpatrick from the Museum Archives or read the article entitled 'Crazy Old Randolf Kirkpatrick' by Steven Jay Gould in his book The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History. Read on to find out about some of the projects that the collection has been used for.

Evaluating past climates and extinctions

Naturalis Biodiversity Center researcher Laura Cotton studied for her PhD in the UK and has been a regular visitor to our LBF collections. She borrowed some rock sample material from Melinau Gorge in Sarawak, Malaysia that was worked on by one of the leading LBF workers of the time, former Natural History Museum Palaeontology Department Associate Keeper Geoff Adams (1926-1995). It would have been almost impossible to arrange for this material to be recollected.

In a study published earlier this year, Laura carried out destructive techniques on these samples to release whole rock isotope data that has provided information about the position of an isotope excursion that relates to a period of global cooling and climate disruption. Laura showed that an extinction of LBFs previously described by Geoff Adams occurred prior to this isotope excursion, a situation she had previously described in Tanzania. This suggests that this Eocene-Oligocene extinction of LBFs is a global phenomenon, closely linked to changes in climate around 34 million years ago.

Boxes at our Wandsworth stores containing samples from which much of our larger benthic foraminifera (LBF) collection was obtained. Please note that the temporary box labels in this 2007 picture have now been replaced!

Most of our micropalaeontology rock sample collections are housed at our Wandsworth outstation and this project is a very good example of how duplicate samples are valuable resources for later studies using new techniques.

Studying hotspots of biodiversity in SE Asia

Naturalis researcher Willem Renema has been studying LBFs from SE Asia as part of a large multidisciplinary group including my colleague Ken Johnson (corals). The 'coral triangle' situated in SE Asia contains the highest diversity of marine life on Earth today. Back in time, water flowed from the tropical west Pacific into the Indian Ocean (Indonesian Throughflow) but this closed during Oligocene - Miocene times roughly 25 million years ago.

This interval in geological time is characterised by an apparent increase in reef-building and the diversification other faunas including the LBFs and molluscs, leading to the formation of the present day 'coral triangle'. The project aims to investigate how changes in the environment led to the high diversity of species present today.

Some slides from the Geoff Adams Collection from SE Asia scanned by Malaysian intern student Zoann Low.

Our LBF collections are very strong from this area of the world following the work of Geoff Adams. Two curatorial interns Faisal Akram and Zoann Low from Universiti Teknologie PETRONAS in Malaysia have helped greatly to enhance this area of the collection by providing images and additional data relating to Geoff Adams' collection and allowing us to prepare data to be released on the Museum data portal and for this 'coral triangle' project.

Supporting Middle East stratigraphy

One of our most important collections, the former Iraq Petroleum Collection contains many LBFs that help to define the stratigraphy of oil bearing rocks of the Middle East. Some significant early oil micropalaeontologists such as Eames and Smout of BP also contributed to the collection.

Recent donation from Oman of some Permian larger benthic foraminifera (LBF) of the genus Parafusulina.

A major publication on the collection by Museum Associate John Whittaker and others is being updated by John and a team of scientists including our own Steve Stukins and Tom Hill. We look forward to seeing this published in a major book in the next couple of years.

Atlas of larger benthic foraminifera

LBF worker Antonino Briguglio was successful with an application to SYNTHESYS, a European fund that facilitates visits to museum collections for European researchers. He visited us in March at the same time as Russian LBF worker Elena Zakrevskaya as part of work to compile an Atlas of LBFs. Antonino's work has included CT scanning LBF specimens and a video showing the architecture of the internal chambers of Operculina ammonoides:

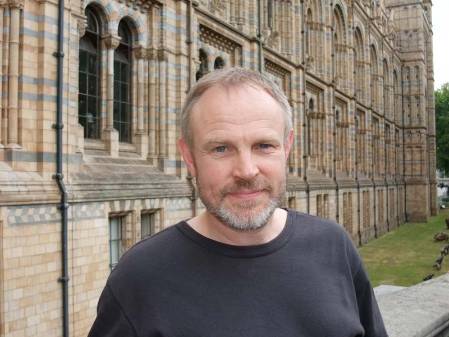

CT scanning has opened up a whole new method for studying LBFs and made it much easier to create virtual sections through specimens without the need for expert and time consuming thin sectioning. We hope that our collection can be an excellent source for those wishing to CT scan LBFs and recently we were in negotiations with long term Museum visitor Zukun Shi who is studying fusuline specimens like the ones illustrated on my hand above.

This collection may never be as important as Kirkpatrick thought it was. However, it is a really excellent example of one that has become more relevant recently as new techniques are applied to its study.