We are showcasing our microfossil tree on the Climate Change Station at the annual Science Uncovered event on Friday 26 September. This remarkable item was created and generously donated by Chinese scientist Zheng Shouyi, and in this post I'll explain how it demonstrates the beauty and composition of foraminifera, climate change and our unseen collections.

The microfossil tree will be on display at Science Uncovered on the 26 September.

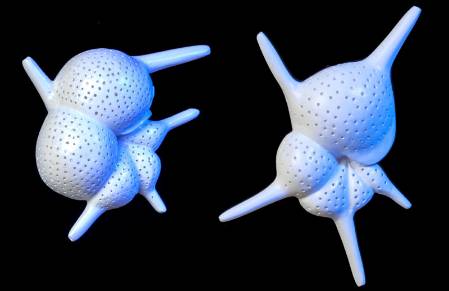

A 6ft aluminium stand with 24 arms hangs 120 plastic models of different species of foraminifera and was generously donated to us earlier this year by Zheng Shouyi of the Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao. She is famous for commissioning and overseeing creation of the famous Foraminiferal Sculpture Park. The models on our tree are magnified 10s to 100s of times.

Species modeled are mainly living examples present in the China Sea and described by Zheng Shouyi during her research. Fossil forms have also been chosen to represent the remarkably wide range of shell compositions and structures created by the single-celled foraminifera. Shouyi was originally inspired by the famous French palaeontologist Alcide d’Orbigny, who created sets of models in 1826 to illustrate the first classification of the foraminifera.

I have chosen four things that our tree shows. There are undoubtedly more and we look forward to discovering them over the next years. Here they are:

1. The beauty of the foraminifera

Everyone who sees our tree remarks how beautiful it is. Zheng Shouyi created them for 'the public to have a share of the diversified and exquisite beauty of the one-celled foraminifera endowed on them by Mother Nature, to inspire scientific, aesthetic and cultural innovations'. Science Uncovered is therefore the perfect venue for us to show this tree in public for the first time.

2. Foraminiferal shell composition

The colours, lustre and textures of the models reflect differences in wall structure and chemical composition of the foraminifera. Most foraminifera are composed of calcium carbonate but the agglutinating foraminifera construct their shells from grains of sand or any suitably sized items available from the ocean bottom. Models representing agglutinating forms on the tree have a sandy texture and mainly a sandy light brown colour to reflect this.

Other forms of calcium carbonate secreted by foraminifera include the porcellaneous varieties where the models appear shiny and milky white. Some calcareous foraminiferal shells of are transparent and glassy while others have translucent white shells that can be perforate or imperforate.

Models of Cribrohantkenina inflata Howe and Hantkenina alabamensis Cushman.

3. Climate change

Two species of hantkeninid foraminifera present on the tree illustrate an interesting story of climate change relating to the fossil record of foraminifera. The extinction of the hantkeninds at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary (about 33-34 million years ago) is thought to relate to fluctuations in climate related to global cooling.

Because planktonic foraminifera, such as the hantkeninids, secrete their shells from the ocean water they lived in, studying isotopic changes in their shell composition can provide information about past changes in ocean composition that are linked to climate. The modern day distribution of planktonic foraminiferal species is often latitudinally restricted, with some preferring cold polar rather then warmer equatorial waters. Studying assemblages of different species in a sample can therefore give past indications of climate.

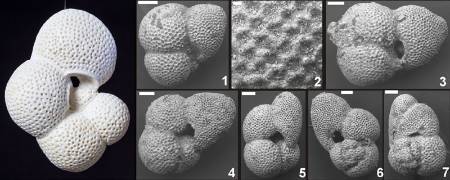

Zheng Shouyi's model of Globigerinoides sacculifer (Brady, 1877) alongside (right) scanning electron microscope images of lectotypes and paralectotypes of the same species from our collections. Images published by Williams et al. (2006) in a paper that I co-authored.

Large numbers of specimens can be recovered from relatively small core samples drilled from the ocean bottom, such as the core that we are showing at the Science Uncovered Event. This makes planktonic foraminifera key to studies in past climates based on the marine stratigraphical record.

4. Our type collections

The tree includes 11 examples of species for which we hold the type specimen. These include examples from historically significant collections such as Brady’s foraminiferal types from the Challenger Collection, the Heron-Allen and Earland Collection and W. K. Parker's types.

We think our microfossil tree fits perfectly with the idea behind Science Uncovered, where scientists come out from behind the scenes to share science and collections that the public would not normally see or perhaps realise existed. If you are in London on 26 September we hope you can come and join us on the Climate Change table under the Darwin Centre cocoon for Science Uncovered.