Curators at the Museum receive donations or offers of donations of new specimens on a regular basis. An interesting rock made almost entirely of microfossils arrived from Brazil a couple of weeks ago. We have not officially accepted this donation yet, but this is an interesting acquisition story about an interesting specimen.

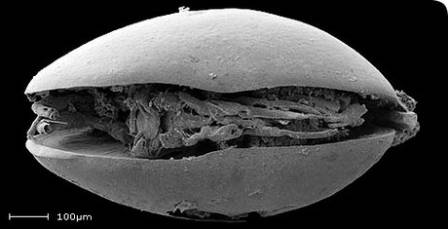

The rock specimen offered for us as a donation

The donor Prof. Dr. José Luiz Lorenz Silva offered the specimen to us following his publication on a rock called a spongillite which was found at Très Logoas in the State of Matto Grosso do Sul, Brazil. This rock was deposited in the Late Pleistocene period about 37,000 years ago in a freshwater pond. The microfossils contained suggest that the climatic conditions were colder at that time and that it was deposited in a slightly acidic peat bog pond.

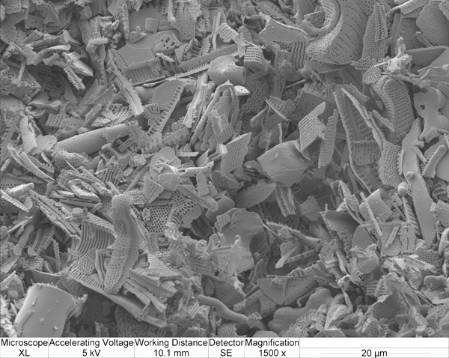

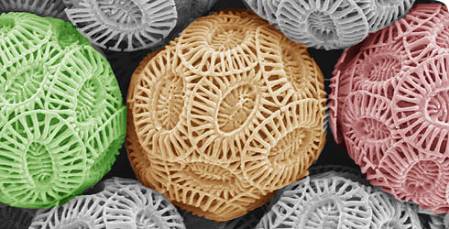

Following the donation, my Erasmus student Angelo Mossoni and I placed a fragment of the rock under the scanning electron microscope to see what it contained. The rock is very light as it is composed almost completely of the siliceous remains of sponges and diatoms. Diatoms are algae that secrete a characteristic shell wall or frustrule of silica. They can be found in the fossil record as far back as the Jurassic period and are commonly used in the present day as indicators of water quality.

A scanning electron microscope image of part of the rock showing the remains of thousands of diatoms

At the start I mentioned that we had not officially acquired this specimen. All future donations are carefully scrutinised so that we are sure that the material has been donated to us without contravening laws of the country that it was collected from. Brazilian law states that specimens cannot be collected from their country and sent abroad unless relevant agreements exist between the institutions in Brazil and the institutions accepting the donations.

To account for this, we have registered the specimen as "Object Entry". This means that we are not certain just yet if we have the correct paperwork and agreements in place to accept it and acknowledge that we do not officially hold title to its ownership. Specimens sent to us for identification or specimens belonging to other institutions but being studied here are commonly registered here as "Object Entry" until they are returned to their owners.

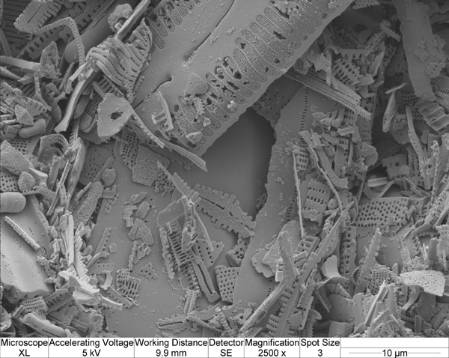

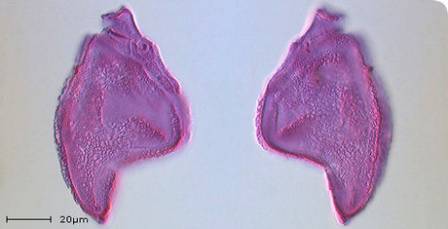

Some more diatoms under the scanning electron microscope. The scale on the picture is 10 microns which is 0.001 of a millimetre.

As you can see from the scanning electron microscope images above, it is certainly a very interesting rock. Museum policy on acquisition states that we will seek to acquire specimens if one of the following is satisfied: it helps to bridge or fill gaps in collections, it fulfills a research need, it complements existing specimens in our collection, it has potential for public education or display, it is scientifically or historically significant.

The spongillite certainly covers several of these criteria and may well be of interest to the research of scientists in the Botany Department studying diatoms. My colleague Martha Richter is currently in Brazil and will be checking if the documentation we have is acceptable. Until we are sure, this very interesting rock specimen won't officially be making its way into our collections just yet.