September 2011 is the 18th anniversary of my arrival at the Museum when I started as a volunteer. I came straight from university as a fresh-faced graduate desperately seeking some work experience to pad out my CV. A brief 3 month spell of volunteering ultimately shaped my future career. Volunteers are vital to the running of the Museum but I would argue that this is not just a way for the Museum to get work done for nothing. Volunteers also gain valuable experience to help them with their futures. Some of my previous volunteers have gone on to jobs in the museum sector, to postgraduate degrees and even to industry.

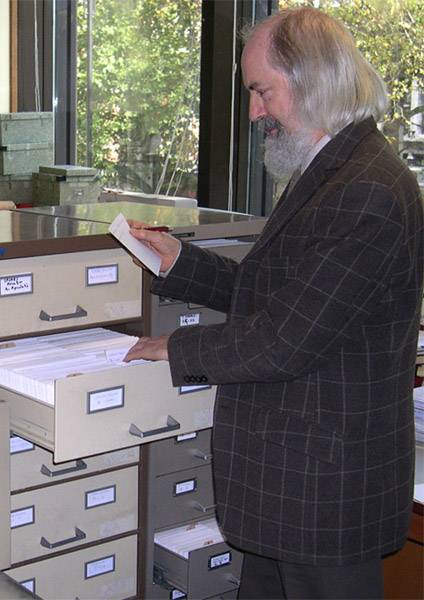

My current volunteers Johanna and Daryl working in the Micropalaeontology Library

To recruit volunteers we first have to write a simple task description that gets advertised on the Museum's website and prospective volunteers are asked to apply. My two current volunteers Johanna and Daryl were recruited because of the skills they could offer to the museum but also because the tasks needing doing suited the directions they wish to take in their careers.

Johanna is considering training to become an archivist. She originally did a Zoology degree and has always been passionate about the Natural World. "I chose this project because it gave me the opportunity to find out what this kind of work would be like in a Natural History context.

I am enjoying the process of being involved in this project and the historic context of the subject in a museum environment. The experience so far indicates to me that I would really enjoy being an archivist in a Natural History context."

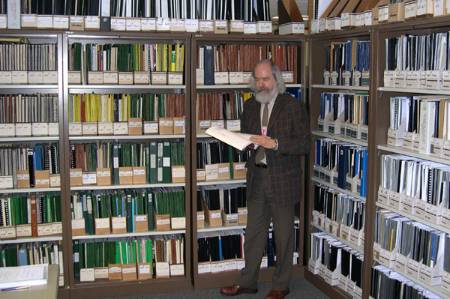

Some of the references that have been sorted by Johanna and Daryl

Initially Johanna and Daryl both worked on a project checking potentially duplicate scientific literature against lists of materials we have in the Museum already. Over the last 10 years we have accumulated vast quantities of micropalaeontological books and offprints, many of which are duplicate. We are under pressure for space so we need to identify which items can be disposed of to make room for our ever expanding fossil collections. These items are often consulted by visitors to the collections and are a useful resource in managing and documenting the fossil collections we hold.

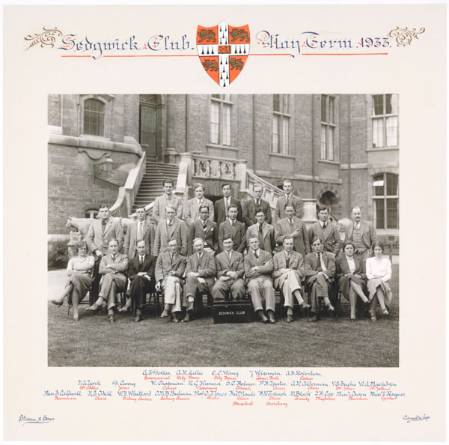

One of the pictures archived by Johanna. Dennis Curry, former Director of electrical firm Currys and amateur micropalaeontologist is on the second row. He donated his collections to the Museum and made funding available for their curation.

Johanna has subsequently moved on to projects related to archiving, and more recently sorted and documented a series of portraits of famous micropalaeontologists. These will soon be making their way to the Library and Archive collections. Daryl is now working on updating the information about a collection that has recently been published in a book.

Daryl says that, "volunteering within the department has allowed me to experience some of what it must be like to involved in collection management and I can certainly say that it is a path I would like to follow, and I believe that what I have learned, and will learn, is a helpful step towards this. The cross referencing and alphabetising of articles has also allowed me to gain skills which could be transferrable to other fields."

One of my colleagues recently passed me the letter I wrote to the Keeper of Palaeontology volunteering my services back in 1993. I remember phoning the Keeper's Secretary asking to whom I should address my application letter. Getting volunteer opportunities at the Museum is a lot easier and a lot better organised these days. If you fancy a spot of volunteering then details of current volunteer opportunities are available on the Museum web site.

Johanna and Daryl have certainly made a big impact on the physical organisation of the micropalaeontology section here. I hope that their experiences here will also help them with their long term futures.

2759 Views

0 Comments

4 References

Permalink

Tags:

giles_miller,

micropalaeontology,

volunteer,

dennis_curry