To celebrate the United Nation's Year of Biodiversity last year, the Museum published details of a different species every day on its web site under the title Species of the Day. These records were delivered last week to another web site The Encyclopedia of Life. Each species was chosen and written about by a museum scientist so this week's blog is to point you in the direction of the microfossils which were chosen for their importance in studies on climate change, ocean acidification, north sea oil exploration and the fossil record of sexual reproduction. Follow the links below to find out more about each species and the groups to which they belong.

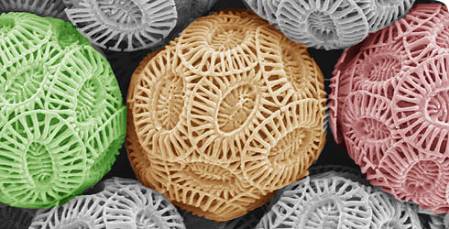

Emiliania huxleyi

Emiliania huxleyi is a coccolithophore which is a unicellular plant that lives in the upper layers of the ocean and forms tiny calcareous coccolith plates like the ones you can see above. These are artificially coloured images from a scanning electron microscope. This very high powered microscope is needed as they are only tens of microns in size and as a result are usually referred to as nannofossils. The ones above are only slightly larger than a thousanth of a millimetre in size. If you were to dip a bucket in the ocean you could find literally tens of thousands of these types of cells. In early summer, E. huxleyi forms enormous blooms across the northwest European shelf that can be seen from space. Coccoliths are susceptible to changes in climate and ocean acidification. This, combined with an excellent fossil record makes them an essential group in the study of recent changes to our oceans and environment.

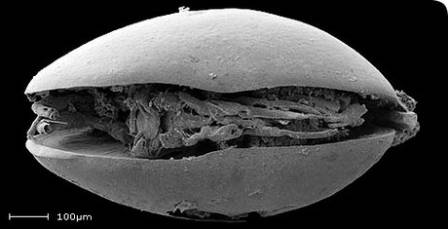

Harbinia micropapillosa

Harbinia micropapillosa is an ostracod, a microscopic crustacean with two calcareous shells. Ostracods can be found in virtually any current aquatic environment and very rarely on land in damp habitats near to water. They have an extensive fossil record because their two shells preserve well as fossils but usually the soft body parts decay soon after death. H. micropapillosa is exceptional because the soft body parts have been preserved in a rock formation that is roughly 140 million years ago. Recent analysis using new techniques has shown the reproductive organs of this ancient organism are identical to those of present day ostracods and suggest that they reproduced using giant sperm back in the Cretaceous period. If you can't wait to find our more about this interesting fossil then follow the link above. However, I will be expanding the story of these important specimens in our collections as the subject of a future blog.

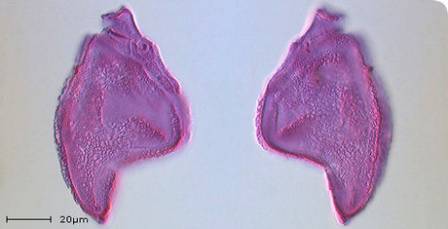

Nannoceratopsis gracilis

Nannoceratopsis gracilis is a dinoflagellate cyst from the Jurassic period about 145-200 million years ago. Dinoflagellates are marine photosynthetic algae that play an important role at the base of the food chain and the carbon cycle. At stages throughout their life cycle they form resistant organic cysts that can be found in the fossil record by dissolving suitable rocks in nasty acids like hydroflouric acid. Nannoceratopsis is one of the earliest forms of dinoflagellate cyst so studies of this genus can tell us a lot about the early evolution of dinoflagellates. The shape is also very distinctive and easily recognisable. N. gracilis can be found in rocks 168-185 million years old and can therefore be used, on its own or in association with other fossils, to accurately date rocks.

Nummulites gizehensis

I mentioned Nummulites gizehensis is a member of the Foraminifera in my second blog and showed a picture of the pyramids at Gizeh that are constructed from rocks that contain this species. The genus Nummulites is a member of a group called the "Larger Foraminifera" that build multichambered shells up to 15cm in size despite being a single celled amoeba. The chambers like the ones shown above can only be seen by breaking the shells apart or making specially oriented thin sections of the rocks they are found in. Sometimes symbiotic green algae also lived in the chambers, providing products of photosynthesis to the amoebe while using the shell as protection. N. gizehensis lived during the Middle Eocene epoch about 37-48 million years ago, in shallow marine conditions and can be used as a marker to show the age of rocks that contain them, particularly in the oil region of the Middle East.

Finally a big thank you to my former colleagues Jeremy, Susanne and Clive who originally wrote about three of these beautiful microfossil species of the day.