My diary this week is illustrated by an item from behind the scenes at the Museum for each day. The week's events include:

- an offer of an important historical collection for sale

- work towards digitising an amazing collection of marine plankton pictures

- hosting an old friend from Brazil

- a recent donation appearing in a publication

- preparation for a session on the scanning electron microscope

Monday

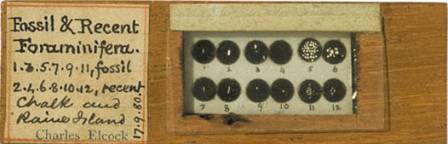

Below is an example from our collection of a slide made by the famous slide mounter Charles Elcock in 1880. Slides made by Elcock fetch as much as £350 on the open market so it was very exciting to be approached by a dealer to see if we wanted to acquire his foraminiferal collection and archive. Unfortunately the asking price was significantly more than we can afford.

A slide from our collections made by Charles Elcock in 1880.

A slide from our collections made by Charles Elcock in 1880.

We regularly buy specimens, and in fact some of my colleagues recently purchased specimens at the Munich Rock and Fossil Show. As far as I know, the last item bought for the micropalaeontology collection was a conodont animal back in the late 1980s.

At the very least this collection offer makes me realise the monetary value placed on historical items in the collection that I look after.

Tuesday

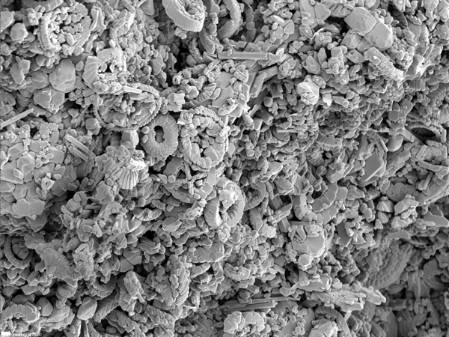

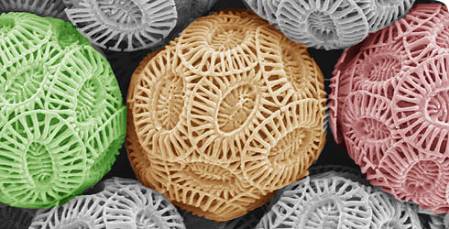

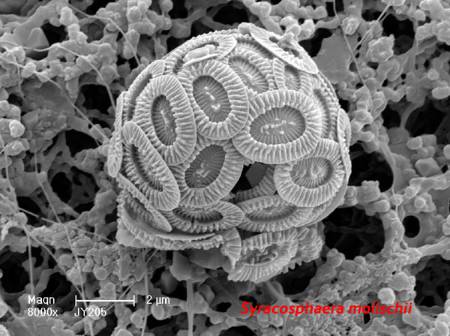

Below is a scanning electron microscope image of a coccolith, part of a collection of over 6,000 images taken by my former colleague Dr Jeremy Young and his collaborators.

Scanning electron microscope image of the coccolith Syracosphaera molischii.

Scanning electron microscope image of the coccolith Syracosphaera molischii.

Recently graduated micropalaeontology Masters student Kelly Smith is visiting today to help us work up the data on this collection so that we can make information and images available via our website. Because their distribution is controlled largely by temperature, coccoliths in ancient sediments have been used to provide details of past climate change.

Coccoliths make their tiny calcareous shells by precipitating calcium carbonate from seawater so their present-day distribution may have been affected by acidification of the oceans relating to the burning of fossil fuels.

Wednesday

In 20 years at the Museum I have met a lot of people from all over the world, some of whom have visited regularly and subsequently become good friends. I first met Prof. Dermeval do Carmo of the University of Brasilia, Brazil, shortly after I arrived at the Museum. We have enjoyed a long collaboration that has included working together on publications, teaching collections management in Brazil, fieldwork and even holidays. He is visiting with a large, empty suitcase to to pick up the last of the scientific papers identified as duplicate by some of our volunteers.

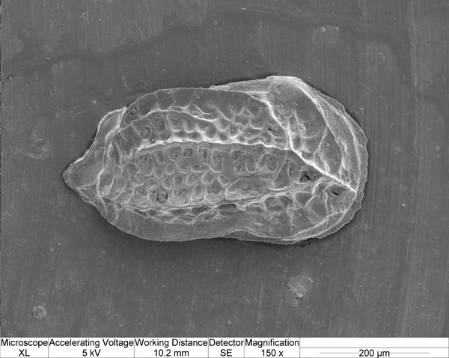

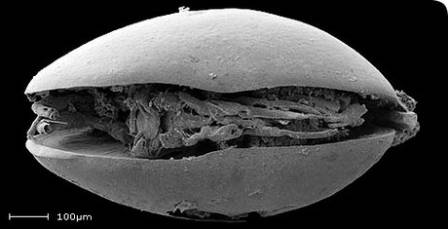

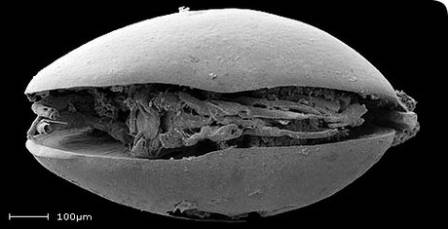

The Brazilian Cretaceous non-marine ostracod Pattersoncypris micropapillosa.

Today's picture is the exceptionally preserved Brazilian Cretaceous non-marine ostracod Pattersoncypris micropapillosa. Dermeval has recently reclassified the genus under the name Harbinia and is on his way to China to look at the type material for this genus. Species related to Pattersoncypris/Harbinia are used to provide information on rock ages and environments of deposition for oil exploration offshore Brazil and W Africa. For more details about their evolutionary significance, see my post on What microfossils tell us about sex in the Cretaceous.

Thursday

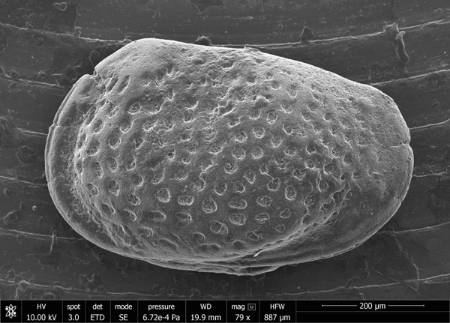

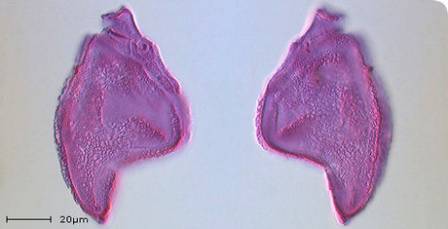

Today's scanning electron microscope image is the holotype of a new species of planktonic foraminifera Dentoglobigerina juxtabinaiensis, donated last summer and published last month in the Journal of Foraminiferal Research by University of Leeds PhD student Lyndsey Fox and her supervisor Prof. Bridget Wade.

The Museum collection contains many type specimens that ultimately define the concept for each species. As a result, types are some of our most requested specimens by visitors or for loan.

The holotype of a new species of planktonic foraminifera, Dentoglobigerina juxtabinaiensis.

This species is Miocene in age (roughly 13.5-17 million years old) and was recovered from an International Ocean Discovery Programme core taken from the Pacific Ocean near the equator. Foraminifera, like the coccoliths mentioned earlier, are important indicators of ocean condition and climate, so this unusually well-preserved material is an important contribution to their study. Now the paper has been published I am able to register the details in our database and these will go live on our website in a couple of weeks.

Friday

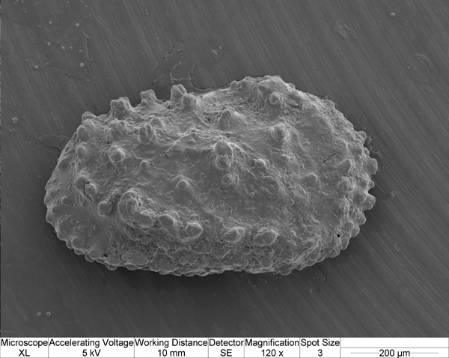

I have a scanning electron microscope session booked next week as I have been approached by a colleague at the British Geological Survey who is preparing a chapter for a field guide on Jurassic ostracods. He would like some images of some of our ostracod type specimens from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of Dorset.

The ostracod Mandelstamia maculata from the Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay of Dorset.

Each specimen must be carefully removed from the slides that house them using a fine paint brush and glued to a small aluminium stub about 1cm in diameter. These will be coated in a fine layer of gold-palladium before being placed in the scanning electron microscope chamber next week for photography.

It proves very difficult to identify the relevant specimens as the original publication is pre-scanning electron microscope times and the images taken down a binocular microscope are less than clear. Publishing new, clearer illustrations of each of these type specimens will add considerable scientific value to our collections.

This selection of specimens has hopefully shown the historical, scientific and monetary value of our collections while showing that they are also relevant to important topical issues such as climate change and oil exploration.

+u1337a+42xcc_blog.jpg)