Crystal Palace Transition Kids and Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs swab the first ever dinosaur sculptures the world had ever seen, to help us identify The Microverse. Ainslie Beattie of Crystal Palace Transition Kids and Ellinor Michel of the Museum and a member of the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs report on the event:

Looming out across the lake in front of us are dinosaurs, 160 year old dinosaurs! They look huge, ominous and exciting! These were the first ever reconstructions of extinct animals, the first animals with the name 'dinosaur' and they launched the 'Dinomania' that has enthralled us ever since.

Never before had the wonders of the fossil record been brought to life for the public to marvel at. These were the first 'edu-tainment', built to inform and amaze, in Crystal Palace Park in 1854. They conveyed messages of deep time recorded in the geologic record, of other animals besides people dominating past landscapes, of beauty and struggle among unknown gigantic inhabitants of lost worlds.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were built in 1854 to inform and amaze. © Stefan Ferreira

Most people just get to look at them from vantage points across a waterway, but not us! Transition Kids (part of Crystal Palace Transition Town) and Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs arranged special access to collect data for the Museum's 'The Microverse' project. The first outing of the newly formed Transition Kids group started with art and science discovery as we decorated our field journals (every good scientist keeps a field journal full of written and sketched observations, musings and potential discoveries) and observed the subjects from afar.

Transition Kids proudly presenting their field journals. © Stefan Ferreira

Then we started the trek over the bridge, through the bushes and onto the island. Wow, the dinosaurs are huge up close! Our CP Dinosaur ringmaster, Ellinor Michel, from Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, explained to the kids about the conservation of the historic sculptures and gave an overview of the science behind The Microverse project.

The Microverse participants trekking over to dinosaurs island. © Stefan Ferreira

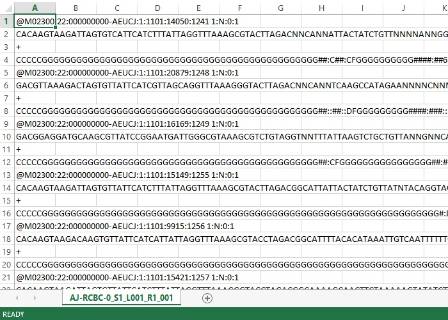

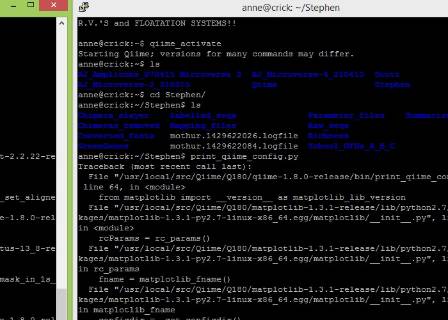

She introduced Dr Anne Jungblut from the Museum who developed 'The Microverse' project, which aims to uncover the diversity of microscopic life on iconic UK buildings. Anne explained what is interesting about the invisible life, called biofilms, on the surface of the dinosaurs. Our involvement in the project is trying to determine what types of organisms are living on the dinosaurs, by sampling and sequencing the DNA!

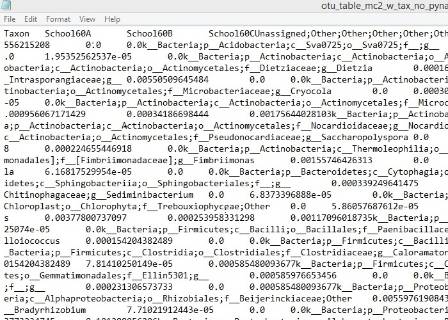

Our results will reveal whole communities of organisms, represented by many phyla of bacteria and archaea, living on each sculpture. Once we get the results back we will be able to investigate which variables affect these communities of organisms, such as substrate, compass direction and distance from vegetation. Then the Museum will compare our results with those from hundreds of other buildings throughout the UK, to look for broader patterns in microorganism ecology. We look forward to meeting again with the scientists to discuss what our results show.

Transition kids collecting samples from the surface of one of the dinosaurs. © Stefan Ferreira

We also took some time to explore the surface of the dinosaurs, describing the textures and patterns that had been sculpted to represent dinosaur skin. Even today, scientists are still discussing the likely skin surface of these great beasts and there is evidence to suggest that some dinos had feathers!

The children also got the opportunity to sit and contemplate the size of the dinos, to look underneath them and across the lake at the diversity of species on display. Not only did they get to see the great big creatures, but also a few living animals when terrapins popped up, dragonflies zoomed past and ducks paddled by.

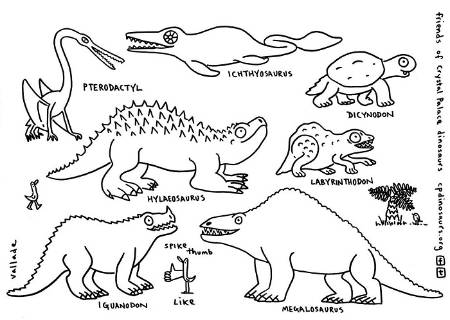

Resident artist David Vallade created a set of drawings the kids could use as a visual aid for exploration. © David Vallade.

During the summer break we will take the kids who participated in the Dino DNA event to the Museum to explore the science behind 'The Microverse' a bit further, and meet more scientists researching our environment in other ways. Starting with this adventure in deep time and now, Transition Kids are planning many more adventures in Crystal Palace Park and beyond.

To find out more about Transition Kids, please email Ainslie

And to find out more about the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs visit: http://cpdinosaurs.org/

A big thank you to all of the Museum staff and local community supporters who contributed to the event.

The whole dinosaur swabbing team. © Stefan Ferreira

Jade Lauren