Today I am observing the fieldwork methods of Museum scientists Jo Wilbraham (algae, including seaweed) and Mary Spencer Jones (bryozoans). We depart on the boat from St.Mary's to St. Agnes at 10.15am in calm waters, under clear blue skies.

St. Agnes is a beautiful island, with many interesting locations to collect specimens. We arrive at low tide, which is ideal for finding a diverse range of seaweed and bryozoan specimens. Jo chooses a beach 10 minutes walk east of the quay, where it is possible to wade far out. It takes a while, and some skilled rock climbing to reach where we are going but once we arrive at the tidal interface the diverse range of species is quickly apparent. We see a wide range of seaweeds, sea anemones and polychetes patiently waiting for the tide to come back in and relieve them from the stress of exposure to the mid-day August sunshine.

Jo Wilbraham examines seaweeds great and small at the beach on St. Agnes.

Jo Wilbraham examines seaweeds great and small at the beach on St. Agnes.

Jo seems quite happy with the spot and comments on the range of species whilst pulling collecting bags and knife out of her pocket and rucksack to begin collecting, making the most of the low tide. The method of exploring and collecting are surprisingly similar to the methods that I use when working in the landscape or on a residency, although the selection criteria and motivation differ considerably. Some of the specimens collected are Furcellaria, Bifurcaria bifurcata and Palmaria palmata.

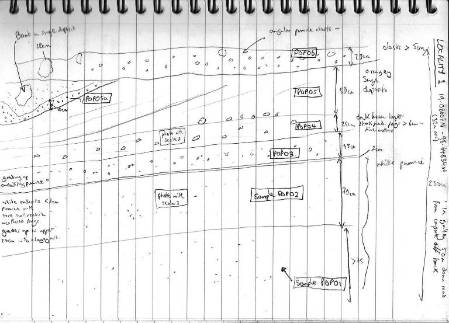

By this point my walking shoes have flooded after being submerged in shin deep seawater and I am inspired to draw some of the collected species on dry land. I am also preparing for the drawing workshop of creative morphology (a method inspired by Goethe’s ‘Delicate Empiricism’) at Phoenix art studios in the evening.

Drying out my feet and drawing seaweed specimens on the beach.

Drying out my feet and drawing seaweed specimens on the beach.

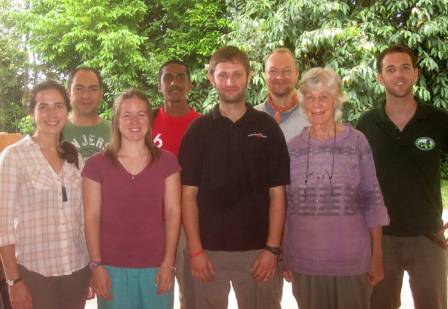

The free drawing workshop is fully booked, and attendees will be almost exactly half Museum scientists and half St.Marys residents or visitors. Due to the demands of fieldwork some of the Museum scientists are late, which means they have a bit of catching up to do. The workshop builds up observational drawing techniques that prepare the individual for a creative exploration of the morphology of the specimen.

Creative morphology drawing workshop

The group produce some very interesting drawings and discussions. One scientist remarks that they did not expect drawing to have method, rather that it was something they associated with scientific work. This point was important as it helped the scientist to acknowledge artistic research and methodology.

Another scientist remarks that drawing helped them to identify important characters of the specimen, and to engage with it. This was helpful as it led to a discussion of the values of drawing and photography/SEM technologies in scientific work. We end the workshop by considering the relationship between the practice of creative morphology and creative evolutionary processes.

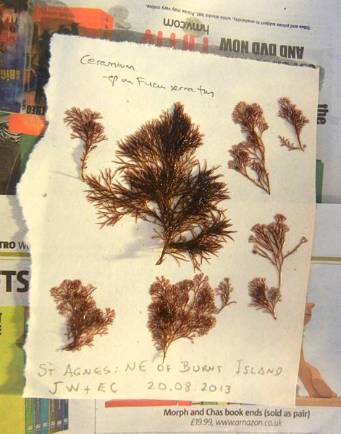

Specimens collected at the beach on St. Agnes are arranged on a herbarium sheet, ready for entering the Museum's collections.

Specimens collected at the beach on St. Agnes are arranged on a herbarium sheet, ready for entering the Museum's collections.

After the drawing workshop I put a few questions to Jasmin Perera, an entomologist at the Museum:

GA: Do you feel the method helped you to 'know' or think about the specimen in a new or different way? If so, could you try to describe this difference?

JP: Yes the method did make me think a lot more about the specimen. It made it far more memorable structurally. There are parts that I would never have thought of analysing so much that I now know exist, which is great because I would feel far more confident in identifying the specimen if I came across it in future.

GA: Do you feel that the method helped you to deepen your engagement with the specimen?

JP: I think I did engage a lot with the specimen, however I feel I get a similar experience when identifying flies under the microscope as the keys we have to follow go into details as little as the length and direction of the little hairs on their body.

GA: Do you think this method could be useful in your scientific or artistic work? If so, how?

JP: I would find this method useful in a scientific environment as it would really make me remember any specimen I came across. Especially by pulling the specimen apart, figuring out all the bits that put it together.

After the drawing workshop I visit the Museum field station at the Garrison, St.Mary’s, where I find Jo sorting through the day's collections, soaking and pressing before carefully arranging on a herbarium sheet. The sun is setting, the team is tired and tomorrow awaits...the marvellous world of insects!

Posted on behalf of Gemma Anderson, an artist and PhD researcher who accompanied Musuem scientists on a field work trip to the Isles of Scilly between 17 and 23 August 2013.

.jpg)