With flights back to the UK this afternoon, there was time this morning for a final visit to the Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) campus. Dan, Kerry and I took the opportunity to have a closer look behind the scenes of the Institute for Tropical Biology and Conservation, part of UMS.

The insect collections at the Institute, kept in row upon row of cupboards and drawers.

The Institute has an insect collection of more than 10 000 specimens, kept in sealed drawers and cabinets, in a room where the temperature and humidity is carefully monitored. They also have a wet collection (where specimens are preserved in alcohol) including fish, amphibians and snakes, and a botanical collection of more than 6000 specimens of plants and fungi. The majority of specimens kept at the Institute were collected from various locations in Sabah, and it is here that our specimens of invertebrates and lichens will have a permanent home in the future.

Dan admires the collections at the Institute.

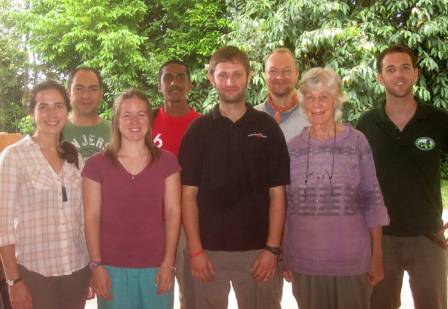

It has been a tiring but memorable six weeks for Pat, Holger, Dan, Kerry and Keiron in Borneo. They’ve visited, collected from and sampled three different areas in Sabah and have a lot of hard work and study still to come. I asked each of them about their memories and experiences of the trip.

Holger

I asked Holger if anything had surprised him during his time in Borneo… ‘I had very low expectations for my area of special interest, which is aquatic lichens. Lowland tropical areas tend to have very few of them. But here there were quite a lot and even in the secondary forest, where there are properly managed fragments preserved along the rivers, the river lichens looked pretty good and there was an amazing species diversity. There is quite a lot of damage in the forest but if habitats are managed properly there’s hope to save quite a significant number of this unique diversity.’

Kerry

Kerry told me about her highlight of the trip… ‘At home I work with tropical butterflies and seeing them in the wild, flying around, has been the best part for me.’

Keiron

I asked Keiron what had struck him most about the differences between Borneo and the UK… ‘There are the obvious things like the different trees and mammals, like the monkeys, that we don’t get back home. But what I’ve really enjoyed is the all the big invertebrates that we get in the forest, like the scorpions and the stick insects, the praying mantids and the beautiful fulgorids. It’s been a real pleasure to see them.’

Tony

Tony has been busy following and filming the scientists over the past two weeks. Here’s what he had to say… ‘It’s been an amazing experience, seeing the rainforest and working in that environment. It’s been tough, carrying equipment and filming in those conditions, but it was worth it. The highlight for me has been seeing and filming the gibbon, gibbons don’t get enough attention! I’ve also really enjoyed working with the scientists, they’re a great group of people and a pleasure to work with.’

Pat

Pat has done a lot of fieldwork in the tropics over the years, I asked if anything had really struck her about this trip… ‘I’ve never been to Maliau before, so this forest has been amazing to me. It’s a forest that you can really work and move in, despite it being so diverse and such a huge amount of species. It really contrasted with the terrible SAFE site where there are all these spiny rattans and lots of vines and the slippery mud….I really thought I wasn’t going to survive!’

Charlotte

For me, I have had an incredible and memorable couple of weeks. I have learnt so much about tropical rainforests and the species that live there, and the enthusiasm and passion of the scientists I have had the privilege to work with has been contagious. I would like to thank all the people at the Natural History Museum who have helped support me over the past few months and have made this blog and the various public and school events possible. It’s been a real team effort and I couldn’t have done it without you! I will miss the rainforest, it’s smells and sounds, it’s towering trees and incredible wildlife, but I have lots of wonderful memories to last me a lifetime!

Dan

One of the things Dan is most looking forward to on returning home is food! We’ve had a lot of rice in Borneo and Dan can’t wait to dig into lasagne, bangers and mash, and cottage pie. I asked him to sum up the past six weeks and what the future holds…

Dan has the final word.

Don’t forget, you can read more about Dan’s experiences in Borneo on his blog. We’ll have a final Nature Live event with Dan in November, giving you the opportunity to ask him your questions and hear first hand about the highs and lows of his time in Borneo.

Thank you for following the blog and for all of your comments and questions – keep them coming!