It's taken a while for me to get back into the swing of things after my return to London, but at long last here's what happened on the last few, hectic days in Mexico, which included one last day in the field to collect our final samples:

A 05:00 start was a harsh way to take on the most challenging climb of the trip but by then Chiara and Dave were ready. Although as they trooped out to the jeep, heavy limbed, it was hard to discern that they knew it. Your devoted reporter remained on the bench in Amecameca on the basis of a four-only-in-the-jeep rule; jealous of the landscapes the rest of Team Popo would see and the last chance at such physical endeavour.

I wanted to leave town exhausted but I'd just have to leave educated and elated instead. On writing and curation duties, I was to source rock-packing materials, a somewhat vital task, so was spurred on in the role. In preparation, I demolished huevos rancheros and set off with the sun on my face, a less than ideal command of the language and immense purpose.

Forget what you know about eating fried eggs, tortillas, cream and green chilli sauce at different times.

When riding other animals, it's customary to do it contraflow to heavy traffic.

My insight into the last day of scientific field work on Popo came as the team arrived back at base early in the evening. They looked at the peak of their exhaustion. We dined quietly but when asked how the day went, Dave gave a dazzling smile and explained how in his element he was. 'Where did your energy come from?' I asked. 'I don't know, he replied. It was some kind of euphoria. I just kept on going, following my body rhythms.'

Reaching their highest altitude yet of 4,474m, Chiara too had a strong final day in the field. She described how for her, Hugo had set the pace and by 'making small footsteps in his wake', she could maintain the energy to make it. 'Without Hugo, I would have failed,' she said, with what's become her trademark grin and shrug of the shoulders.

Hugo: Two steps ahead and a dab hand with a 5kg mallet. He's a field work essential.

Popo: Quietly cultivating a 50-a-day smoking habit.

Beautiful Monarchs converge on an outcrop.

I'll name that layer in one.

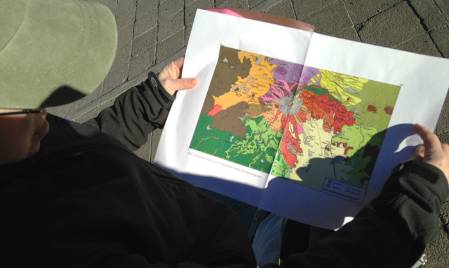

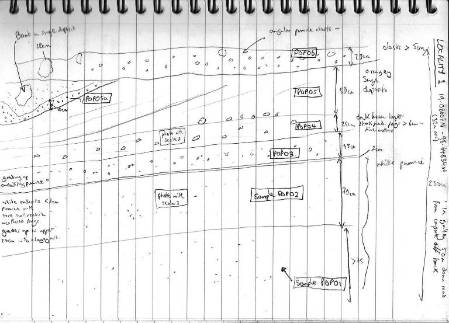

Chiara's research will very much depend on the data she generates once she's tested these samples back at the Museum. However, as the week progressed it's clear Dave can already see how his work here will enhance the Museum's collections. The Popo samples from this trip will have context of the type he rarely sees in the collection, with his photographs and field sketches giving an exact visual of the make-up of each outcrop.

This, along with the GPS and field notes places the sample more firmly at it's location and - to fully understand Popo - this helps immensely. 'It was also great to get back into making sketches,' he says. 'To be here to collect from the source is invaluable. I have much more to information to offer those wanting to use these collections now.'

Dave tells me his drawings have been 'enhanced' by years of doodling with his two kids.

Local dining requires rapid response paperware.... In truth, our visit to procure more packaging for the specimens.

Amecameca prepares for a two week festival as we depart (a coincidence?)

I don't know what he's selling but I want one.

Lost Highway: Laden with rocks, Dave and Chiara's taxi takes ten wrong turns too many. Mostly to the right.

If any of you have seen the film, The Canonball Run, you will have some insight into the way Mexican highways and byways work. As Chiara and Dave's taxi heads for Mexico City and the beginning of our journey home, we spot a car boot full of people with their legs sticking out, the vehicle swerving between traffic. My palms begin to sweat at the sight.

The 90 minute journey extends to a joyful five hours as the taxi gets lost and our Sat Nav diverts us to the more 'exhilarating' - i.e. terrifying - parts of town. A lifetime later, we've booked into our hotel and hit the streets of the busiest city I've ever been to and spend the evening re-living the highs and lows of the trip. The sheer volume of people traffic serves only to remind us of the dangers of Popo, a mere 70 kilometres away. It also makes me think of how vital Chiara's research could one day be in predicting their safety.

.jpg)