I spent my formative years living by the beach, so the idea of being able to swim unhindered by lungs that need air to absorb oxygen was a fantastical one. Yes, I daydreamed about being a mermaid.

And, a few years ago, I discovered that mermaids were more than just an object of my imagination, or of myth and fairytale: they were real. Well, at least they were in the form of compound constructions for curiosity cabinets and travelling sideshows...

There are two types of 'mermaids' in natural history: the monkey fish and the 'jenny haniver':

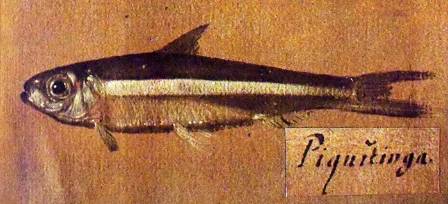

As the name suggests, the monkey fish is comprised of the head and torso of a monkey (carved out of wood) and the tail of a fish, often with additional papier-mâché elements plus wood and wire for structure and support. The jenny haniver is constructed from a guitar fish (part of the Rhinobatidae family of rays) and has been fashioned since at least the 16th century, initially in the image of the lethal basilisk before (by way of dragon, devil and angel) taking on a more human form and being presented as a mermaid.

The mermaid of myth and legend, as depicted by painter John William Waterhouse (left), and mermaids of "reality", aka monkey fish, belonging to the British Museum (top right, © The Trustees of the British Museum) and the Horniman Museum (bottom right).

Ollie Crimmen, the Museum's fish curator, who also has a bit of a soft spot for mermaids, says it's a shame we don't have a monkey fish at the Museum, but was keen to discuss with me the two jenny hanivers held in our stores:

I think when people look at these things with modern eyes they think "how can people believe it?"

[But, in centuries past] when somebody went over the horizon in a ship they were more out of touch than astronauts are today. When they came back, if they came back, there was a huge expectation: "you must have seen something fantastic, you must have brought something back". There was a pressure to have seen marvellous things. It might sound mad to us, but it was the sheer pressure of the expectation of what you've seen once you'd gone over the horizon.

And those who had not been on the journey, who had not seen fantastic, foreign things, were willing to believe whatever was presented to them as fact. For how could they know any different without having ever seen it in the flesh themselves? Remember my mention in a previous blog about the 'legless bird of paradise'?

On the other hand, nature does come up with some very real, very strange creatures. Consider the platypus: when it was discovered in the 18th century many scientists had difficulty believing that its mix of reptilian and mammalian features could be genuine.

The Museum has one quite big jenny haniver which measures 54cm in height, and another 'more quaint, smaller one' that's much older, Ollie says. He's not sure of their origin, but suggests that Museum scientist Peter Dance 'maybe had a go' at making one.

The suggestion is not completely off the mark. In his book Animal Fakes and Frauds, Dance describes buying a jenny haniver in London's Soho around the 1960s or 70s. Perhaps this is the specimen now in our collection.

When I first began gathering material for this book, I found that jenny hanivers were still being made. I bought one in London. According to the proprietor of the shop in Soho, whence I obtained it, it was said to have come from the Gulf of Mexico. It was, he said, a very good selling line, and I know it did not take him long to sell the others he had.

The Museum's large jenny haniver specimen, front (left) and back (right). It measures 54cm tall and 29cm across.

There is no definitive answer as to where the name jenny haniver originates, although many cite 'Anvers' (the French name for Antwerp), as a source, as it was on the coasts of Belgium and Holland that these mermaids were said to have been caught.

Dance's book also includes a passage from Australian ichthyologist Gilbert P Whitley describing how jenny hanivers are made:

...[by] taking a small dead ray, curling its side fins over its back, and twisting its tail into any required position, a piece of string is tied round the head behind the jaws to form a neck and the ray is dried in the sun. During the subsequent shrinkage, the jaws project to form a snout and a hitherto concealed arch of cartilage protrudes so as to resemble folded arms. The nostrils, situated a little above the jaws, are transformed into a pair of eyes, the olfactory laminae resembling eyelashes. The result of this simple process, preserved with a coat of varnish and perhaps ornamented with a few dabs of paint, is a jenny haniver, well calculated to excite wonder in anyone interested in marine curios.

What is presented as the face of the jenny haniver is actually the underside of the guitar fish. The ray's real eyes (located on its upperside) are sometimes obscured by curled pectoral fins. Ollie says:

Some people think it's dark, but it's a part of cultural history, of natural history.

Another jenny haniver specimen, which featured in the Museum's 2010 exhibition, The Deep.