Those who know me know that I tend to get a bit twitchy around flying things (eurgh, pigeons, they're crazy and can't be trusted). But I've never been so scared of a winged creature that I felt the need to pull a gun on it.

But then again, I've never been two days deep in the rain forests of New Guinea and confronted by the world's biggest butterfly, which boasts a wingspan of about a foot wide.

However, in 1906 English explorer and naturalist Albert Stewart Meek found himself in that very situation while on a collecting trip for Walter Rothschild, so he pulled his gun and shot that butterfly right out of the sky.

As a consequence, the Museum's type specimen of the Queen Alexandra’s birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae), has bullet holes in its wings!

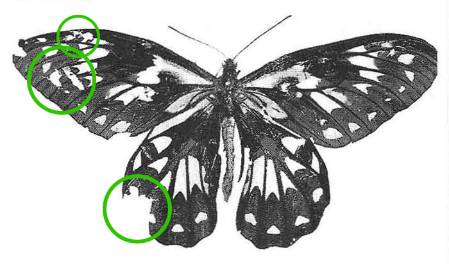

Bottom: The holotype female specimen of Queen Alexandra’s birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae), described by Rothschild in 1907. The large tear in the left forewing and the several other smaller holes and chips (circled), are as a result of it being shot.

Top: How a female Queen Alexandra’s birdwing looks when it hasn't been shot for collection.

At this point I should probably clarify that Meek wasn't using regular shotgun shells but, instead, what is known as 'mustard seed' or 'dust shot' cartridges. These were designed especially for daring explorers and collectors of the time to shoot small birds at short range without causing damage to their plumage.

Meek was also responsible for another addition to our curious collection of 'shot birdwing' specimens, this time a goliath birdwing (Ornithoptera goliath), obtained on Goodenough Island, off eastern Papua New Guinea, in 1914.

In a letter between entomological dealer Oliver Erichson Janson and collector Charles Oberthür, it was written:

[Meek] was only able to obtain a few specimens by shooting them as they always flew only about the tops of the highest trees and he couldn't induce them to come down.

The earliest of our shot birdwings is one captured by John MacGillivray on Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands) in 1854, during the voyage of HMS Herald.

In describing MacGillivray's specimen as Queen Victoria's birdwing (Ornithoptera victoriae) in 1856, George Robert Gray wrote:

Its flight is very elevated; so much so that it became necessary to employ powder and shot to secure the specimen.

Above: MacGillivray's holotype female Queen Victoria's birdwing (Ornithoptera victoriae), with damage from shot.

Below: A Queen Victoria’s birdwing collected using more conventional means.

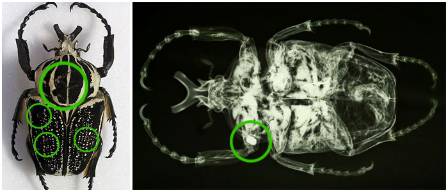

Birdwings are not the only entomological specimens in our collections with bullet holes. We also have a goliath beetle (Goliathus goliatus), captured 125-years-ago, that was recently revealed to have been shot in its back while in flight.

Entry and exit wounds in the goliath beetle, as well as a shotgun pellet still inside its body as revealed by X-ray analysis.