It's almost a year since I started blogging for the Museum, and as I considered what I should profile for my 12th Specimen of the Month, I inevitably began to reflect on all the amazing specimens I've already written about, those on my list to write about in the future (which, for various reasons, can't be featured today), as well as all the specimens I've yet to even discover exist here.

One of the most incredible things about the Museum is just how many specimens we care for. To describe it by coining a phrase from Charles Darwin (although he was talking about the evolutionary Cambrian explosion, but anyway...), the Museum's collection is full of 'endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful'.

So today I thought I would celebrate all the specimens in our collection. All 80 million of them!

As you can obviously gather, not all 80 million are on public display. In fact, only about 0.04% of our total collection is on show in the public galleries. The rest is housed behind the scenes, in specially-built, and often specially-temperature-controlled, storage facilities.

Our 80 million-strong specimen collection is composed of:

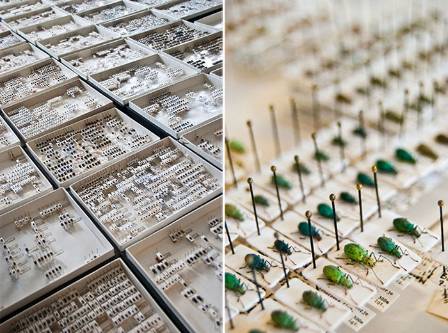

More than 34 million insects in 140,000 drawers, of which 8.7 million are butterflies and moths.

Some of the modern and historic storage cupboards containing the drawers that house our insect collections.

The collection was boosted in 2010 with the donation of 45,000 weevils of 4,500 different species from Oldrich Vorisek, a private collector in the Czech Republic. Half were new to the Museum, and it included almost 750 type specimens. Pictures © Libby Livermore.

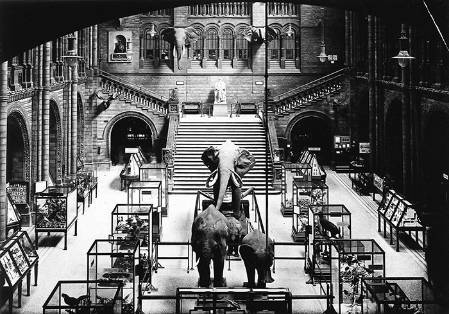

More than 27 million animals, ranging from the smallest fishes and frogs to enormous elephants and blue whale skeletons.

Before Dippy took pride of place, elephants were a dominant feature of Hintze Hall (or Central Hall as it was back then). In this picture from 1924, three elephants can be seen on the main floor, while a further two elephant heads are mounted above the Darwin statue on the stairs.

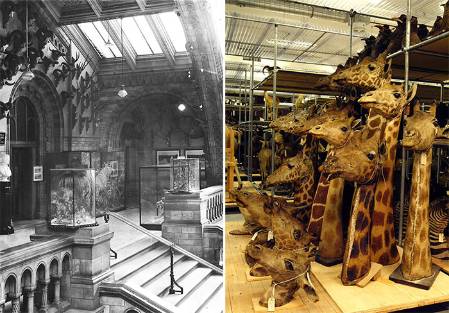

Mounted heads used to be much more prominent around the Museum in years gone by, as illustrated by this photograph of the balcony of Hintze Hall from 1932 (left). [Note, also, the terrifying location of the glass display cases at the top of the stairs!]

Today, most of our mounted animal heads are kept in storage (right).

More than 7 million fossils, with the oldest dating back more than 3.5 billion years.

One of my favourite fossils is this petrified tree trunk: the wood of a conifer from the Triassic era (250-200 million years ago) has been replaced with the mineral agate.

Another fossil I'm quite fond of, which also has a mineralogical connection, is this ammonite (Parkinsonia dorsetensis), from the mid-Jurassic era (174-166 million years ago): its chambers have been filled by calcite crystals.

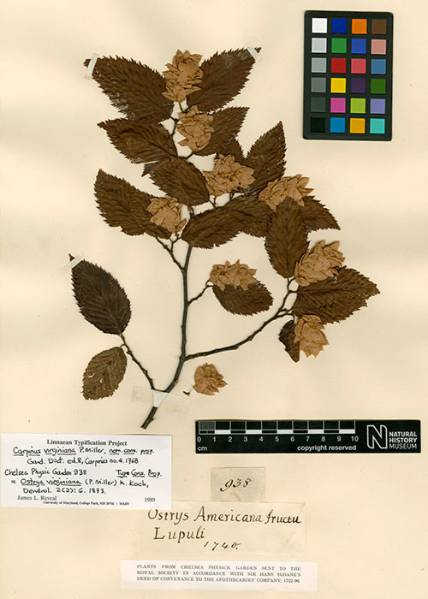

More than 6 million plants, algae, ferns, mosses and lichens, 10% of which come from the British Isles.

Our oldest plant specimen is a mounted American hop hornbeam (Carpinus virginiana), which dates to 1740 and was collected just about a mile from here at the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Watch herbarium technician Felipe Dominguez-Santana demonstrate how plant specimens are mounted in this video from 2009. It was filmed around the time that all our herbarium specimens were moved into the then-newly-built Darwin Centre.

More than 500,000 rocks, gems and minerals, of which 5,000 are meteorites.

Here I am reflected in some pyrite in the Minerals gallery.

For some reason this malachite specimen causes innumerable giggles. We don't know why.

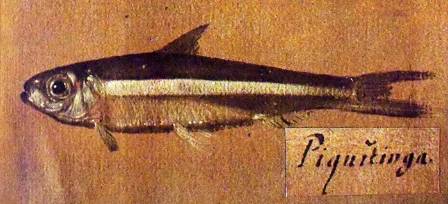

And, more than 1.5 million books and artworks in the Museums Library and Archives.

As a book junkie, the Museum's Library collection (of which there are six sub-collections: zoology, Earth sciences, botany, entomology, general, and ornithology at Tring) is a thing of beauty in itself, to me. This is a view from the balcony over the Earth sciences collection, which is in the old Geological Museum building (now the Red Zone), built between 1929 and 1933.

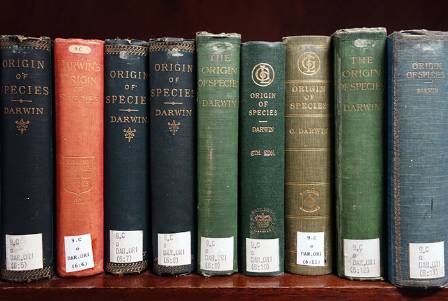

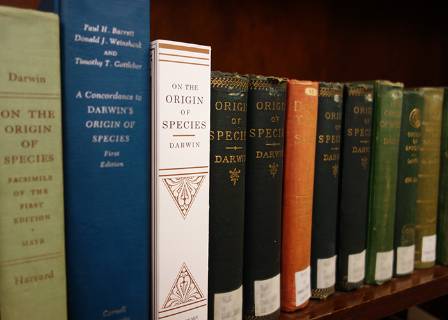

Just a small selection of some of the 540+ copies of Origin of Species held by the Museum's library. We have the largest collection of Charles Darwin's works in the world.

Finally, not officially counted in the 80+ million, but...

The web team's collection of dinosaur toys, totalling 15.