When links began circulating online over the Easter weekend about a reported sighting of the Loch Ness monster, it brought to my mind two interesting little tidbits about the beast that I have learnt during my time here at the Museum.

Satellite view of Loch Ness from Apple Maps, which Andy Dixon and Peter Thain claim provide evidence that the Loch Ness monster exists.

The first tidbit, told to me in the queue to get into our annual staff Christmas sale last year, was that the Loch Ness monster is one of only two scientifically described species that doesn't have a type specimen. A type is the particular specimen of an organism which is used to scientifically describe and name that specimen.

The Loch Ness monster was given a scientific name in the journal Nature on 11 December 1975, in an effort to protect it. Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines wrote:

The Conservation of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants Act 1795 provides the best way of giving full protection to any animal whose survival is threatened. To be included, an animal should be given a common name and a scientific name. For the Nessie or Loch Ness monster, this would require a formal description, even though the creature's relationship with known species, and even the taxonomic class to which it belongs, remains in doubt.

Scott and Rines argued that it was better to be safe than sorry and, citing eye-witness accounts, photographs and sonar images as evidence of Nessie's existence, they proposed the name Nessiteras rhombopteryx. It combines the name of the Loch with the Greek word for wonder (teras or teratos), and the Greek for diamond shape (rhombos) and fin (pteryx), thus: the Ness monster with the diamond shaped fin.

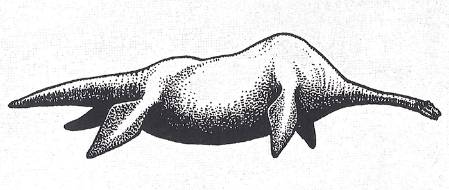

An impression of the possible appearance of Nessiteras rhombopteryx from photographs, eyewitness accounts and sketches derived from a large number of sightings at the surface and from the accompanying underwater pictures, published alongside Scott and Rines' 1975 Nature paper.

Other than Nessie, the only other known species without a type specimen is actually us, Homo sapiens.

The second Nessie tidbit I've comes across during my time here is the arrangement the Museum has (or, at the least, used to have) with William Hill, to adjudicate on evidence presented to the bookmaker by anyone claiming to be able to prove the existence of the Loch Ness monster.

William Hill's Graham Sharpe first made the arrangement with Iain Bishop, the Museum's former deputy keeper of zoology, around 20 years ago. He says:

We quote odds about Nessie being proved to exist, which have fluctuated up to 1000/1 at times, depending on whether and when there have been sightings.

We once got Iain and a couple of members of Museum staff up to the Loch when we organised a Monster Hunt Weekend, offering, I think, £250,000 to anyone who could produce conclusive proof of the existence of Nessie. I remember those days very fondly, and will recall forever the sight of the eccentric rock 'n' roller and politician Screaming Lord Sutch trying to entice Nessie to emerge from the waters of the Loch by tempting her with British Rail sandwiches.

The William Hill-Museum-Loch Ness monster deal was last updated about 10 years ago, between the bookmaker's Rupert Adams and our fish curator, Oliver Crimmen.

The original offer had been based on 'capturing evidence of Nessie on film', but the last agreement stipulated the following identification guidelines:

- The Natural History Museum cannot undertake to identify photographs, sonar traces, written descriptions or other forms of indirect evidence, although would be interested in seeing them.

- The Natural History Museum hopes to be able to detect most hoaxes (eg man-made modifications to bones) but cannot guarantee to identify all fragments and would not regard a determination of 'animal bone unidentifiable' as positive identification of a monster (a small piece of horse rib would probably be impossible to allocate to a species).

- The Natural History Museum will make every effort to provide a positive identification of tangible adequate specimens.

- The Natural History Museum is unsure as to what might constitute a 'monster' though it might define it as a species hitherto unknown to science or widen the definition to include species previously known as fossils. It must be of a similar size to previous eye-witness accounts.

Of course the image visible on Apple Maps does not fall within the Museum's guidelines so, for the time being, William Hill's money goes unclaimed. However, Rupert Adam says:

It is the best evidence we have seen for a couple of years. We are now at 100/1 from 250/1 that Nessie will be found (confirmed by the Museum) before the end of 2014. It could cost us a six figure sum and we have to hope that Nessie does not pop up to trash our Christmas.

Others, though, are not convinced.