Hello Super-flies & Parasites fans!

This time we are departing from the familiar world of blood flukes and having a look at something new and exciting: Welcome to the ‘Forever Flies’series of blog posts. I’ve really enjoyed writing this bit as it’s totally new to me and I’m learning so much from our wonderful scientists in the Forensic Entomology group of the Parasites & Vectors division here at the Museum.

About forensic entomology

I think I mentioned forensic entomology way back in the first ever Super-flies and Parasites post. But to refresh our memories and delve a bit deeper here’s an explanation taken from the group’s website:

'Forensic entomology is the study of insects and other arthropods (ie spiders, mites) in a situation where a crime may have been committed. The insects recovered from a crime scene can provide vital information for the investigating team. The most common role for Museum forensic entomologists is establishing a minimum time since death in suspicious cases, by analysing the carrion insects on the body.'

Flies use the bodies of dead animals to grow and develop, fulfilling a vital nutrient recycling role in an ecosystem. They can turn one vertebrate body into thousands or millions of flies, which are then fed on by other animals - insects, frogs and birds for example. The rate at which they do this, going from eggs to larvae to pupa to adult fly, is pretty consistent.

Knowing enough about the species of flies we can exploit this information when they develop on corpses. By determining how long the insects have been feeding on the tissues of the corpse, we can determine the length of time elapsed since flies found the body; thereby providing crime scene investigators with a minimum post-mortem interval.

Some flies however don’t hang about and wait for death, they prefer feeding on live animal tissues, and can cause a horrible disease called myiasis, a major economic and animal welfare problem.

Female Bluebottle blow fly, Calliphora vicina, and maggots feeding on a dead pig.

Dr Martin Hall and colleagues within the Museum and around the world work together on the taxonomy and biology of flies that develop as larvae on living or dead vertebrate animals. Their expertise and research greatly contributes to the control of a painful and damaging disease, myiasis, but also to the field of forensic entomology, helping CSIs determine crucial information from a crime scene.

So there you have it, some real life crime scene investigation stuff! These are the guys CSIs turn to for help! (Cue CSI theme song!)

The beauty of maggots lies in their mouthparts

I asked Martin for a little blurb to get the Forever Flies series rolling and he sent me some surprisingly beautiful photos of maggots! Here’s what he has to say about them:

To most people maggots are repulsive creatures; they all look much the same and have zero redeeming features.

Maggots, thought of as repulsive creatures with zero redeeming features. Read on to see how they are transformed by confocal microscopy into beautiful works of art.

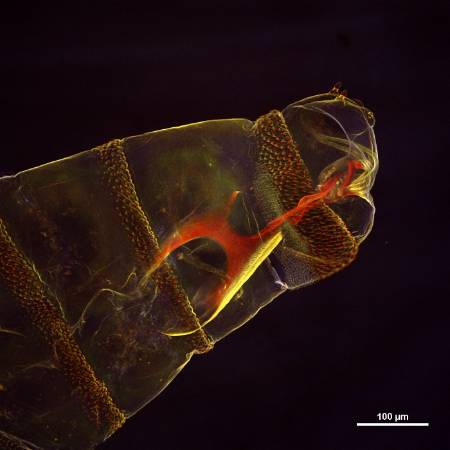

However, viewed under a microscope they become much more interesting, with a range of characters that can be used in discrimination, especially when you look at the business end of the maggot, its mouthparts!

It’s not so easy to ask a tiny 2mm long newly hatched maggot to 'open wide' to view the teeth, and traditionally we have been limited to viewing slide-mounted specimens by light microscopy. Scanning electron microscopy has its merits, but only for the external features. In normal light microscopy, imaging of these mouthpart structures is limited by problems of resolution, illumination and depth of field.

Greenbottle blowfly, Lucilia sericata light microscope high power image. With normal light microscopy the relationship of the sclerites of the cephaloskeleton (mouthparts) to each other is unclear.

At the Museum we have been using a laser confocal microscope for the first time to look inside these maggots to view the mouthparts, the so-called cephaloskeleton, in three dimensions. The mouthparts are crucial to the maggots in establishing themselves on their food source, be it a live animal or a decomposing corpse. The images produced by the confocal microscope rely on the autofluorescence of structures of the cephaloskeleton.

Greenbottle blowfly, Lucilia sericata confocal microscope low power image - relationships are still unclear but, with the autofluorescence under laser light, the structures look so much more beautiful!

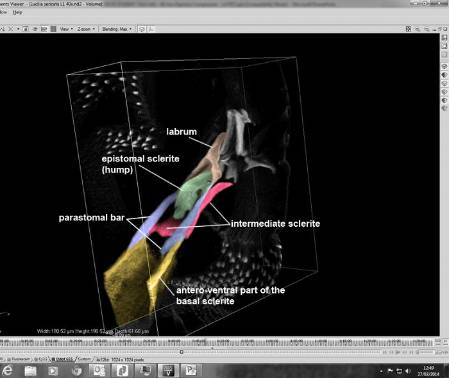

We were especially interested in the relationships of the small sclerites to each other and the so called 'hump', present in newly hatched larvae of Lucilia greenbottle blowflies but absent in Calliphora bluebottles.

Greenbottle blowfly, Lucilia sericata confocal microscope high power image: The structure relationships are becoming clearer (the 'hump' is arrowed) and this is finalised in the next image.

The 177 optical sections scanned by the confocal microscope enabled us to rotate and view this structure in three dimensions (see green false-coloured sclerite in image below) and see clearly for the first time how it relates to other structures.

In addition to their academic and practical value in identification, the images are also things of beauty in their own right and would not look out of place in an art gallery!

Greenbottle blowfly, Lucilia sericata confocal microscope high power image and false colour sclerites. We have rotated the original to give three dimensionality. The red wavelength was selected, as this is the wavelength that gave most autofluorescence of the cephaloskeleton, to enable us to discard other structures and here false-colour has been added to show the different structures, including the 'hump' (in green) or epistomal sclerite.

The work was done at the Museum and involved Drs Andrzej Grzywacz (a visitor under the EC-funded SYNTHESIS project) and Krzysztof Szpila from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland, collaborating with Tomasz Góral and Martin Hall. We used the Museum’s Nikon A1-Si Confocal Microscope.

For more information see the article published online in Parasitology Research on 19 September 2014.

By Dr Martin Hall

I hope you enjoyed the first 'Forever Flies' post. For more on flies head over to Erica McAlister's Diptera blog.

There will be more coming soon but just to let you know there may be a couple of weeks break whilst some important maintenance work is done to the site and my life

See you soon