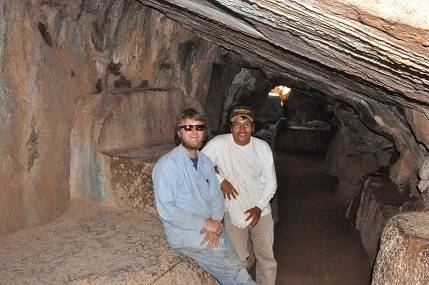

Field work began in earnest today – we headed from the coast up into the mountains, the destination was Cajamarca, by fast road 6 hours away – but we were taking the road less travelled. We took a tiny dirt track up a dry valley to a village called San Benito; our research in the herbarium in Trujillo told us this would be a good place to look for some special endemics. Wild tomatoes are most diverse in the dry western regions of Peru – so I was hoping to see some of the species I have not yet seen in the wild.

It took us a while to find the right road – road signs don’t really seem important in Peru, people generally know where they are going I guess! The area was fantastically dry, with rocky slopes and tall columnar cacti. This is the northern part of the Atacama, the desert created by a combination of the cold ocean current called the Humboldt Current coming from Antarctica and the rain shadow of the Andes to the east.

The tall cactus peeking out from behind the hill is called Neoraimondia; Antonio Raimondi was a famous Peruvian botanist of the late 19th century and really began the exploration of the plant diversity of the country

The first plant we saw (well, the first one we were going to collect!) was a genus I have never seen in the field before – Exodeconus. It is an Atacama endemic, and this species is the only one to grow in northern Peru. Tiina collected a couple of other species last year in the southern part of the Peruvian coast.

The plants we saw in this valley were tremendously variable in size, from tiny with only a couple of leaves to large and fleshy and extending to a metre or more. It all depends on water, as is usual in a desert. Desert plants are masters at making do.

Exodeconus maritimus growing in a shady place under a rock – some leaves on other plants were the size of saucers! The flowers are beautiful, bright white with a deep purple centre

The tomatoes soon began to appear, like Exodeconus growing in slightly wetter microhabitats. The first species we saw was Solanum pennellii – the closest relative of the tomatoes proper. It doesn’t have the pointed anther cone of the rest of the group, so was placed in the genus Solanum, rather than Lycopersicon, as the tomatoes used to be known.

We now recognise all of the wild and cultivated tomatoes as members of the genus Solanum, based on the molecular studies done by my colleague David Spooner in the early 1990s. His results showed tomatoes are closely related to potatoes; many characteristics of the plant form also support this evolutionary relationship. So we now group the tomatoes as part of the large genus Solanum, reflecting their ancestry and evolution more accurately.

Solanum pennellii has stubby anthers – here being buzzed by a small bee

All Solanum species are buzz pollinated by bees – the anthers open by tiny pores at the tips and female bees grasp them and set up a resonance inside using their flight muscles, pollen squirts out lands on the bee and she carries it to another flower – if you sit by flowering tomatoes long enough anywhere, bees will come and buzz, the sound is quite audible!

Tomatoes proper have a long beak on their anther cone, but there are pores inside – the beak is a shared evolutionarily derived character that tells all tomatoes are closely related to one another.

Solanum arcanum – a northern Peru endemic species only recently described by my colleague Iris Peralta (with whom I was recently collecting in Argentina), has the elongate beak typical of wild tomato relatives. This species began to appear a bit further up the valley towards the mountains

The small fruits of wild tomatoes are usually green and hairy, but even from them you can tell the species apart. The sepals of Solanum pimpinellifolium – the progenitor of our cultivated tomato – are strongly turned back, while those of Solanum arcanum (below) are always held flat – easy!

Solanum pimpinellifolium

Solanum arcanum

We were elated with our success at finding the wild tomatoes, all in flower, but were becoming disappointed about one special species we were seeking – Solanum talarense, an endemic to the dry coastal valleys of northern Peru and rarely collected.

We had almost given up, the road was going up the valley into wetter habitats and higher elevations, but then we saw it – possibly the rattiest plant I have ever seen! Eaten by goats, despite its ferocious prickliness, there it was hanging on in rocks by the roadside.

Solanum talarense amongst the rocks, completely eaten by goats (we think, but it certainly had been munched by something!)

Jumping out of the truck I felt prickles in my shoes – only to discover that several 2 cm long thorns had gone right the way through the bottom of my boots; it will be interesting to see how this affects them when we get to wetter places! Solanum talarense was most definitely THE plant of the day, totally weird and wonderful – a plant only a Solanum taxonomist could love.

The 'spines' on the stems and leaves of Solanum talarense are technically prickles, outgrowths of the surface – true spines, like those that went through my boot, are bits of stem. Prickliness does not seem to have deterred the animals eating this plant at all!

Ascents from the coast to the Andes in Peru are amazing – in a single day you can go from sea level and a dry desert to 4000 metres elevation and dripping wet cloud forest. This time we went over a pass that was only 3500 metres elevation, to descend again into the dryer valley of Cajamarca (via a couple of other passes – the geography is incredibly complex in northern Peru).

Wet cloud forest beckons ahead in the mountains

Wet cloud forest beckons ahead in the mountains

In the village of San Benito, in the cloud forest – in the pouring rain – we found our last wild tomato of the day. Solanum habrochaites used to be called Lycopersicon hirsutum, but when the time came to change its name to put it into Solanum, there already was a Solanum hirsutum (a European species) – so we had to think of another species name for it. The name we chose – habrochaites – means softly hairy in Greek; we thought it described the plant exactly.

The fruits of Solanum habrochaites are covered with long hairs each of which has a small sticky gland on top. These glands exude a substance that gives each wild tomato species its particular smell, and gives us that lovely smell of ripe tomatoes fresh from the vine

We reached Cajamarca at about 11 pm, a bit later than planned – maybe we spent too much time collecting in the desert, but none of us thought so! This first day collecting was a great success – lots of other wonderful northern Peru endemics and some real surprises and firsts for me (Leptoglossis schwenckioides, Browallia acutiloba and on and on).

Now for a day in the herbarium of the University of Cajamarca and a visit to the wonderful Peruvian botanist Isidoro Sánchez Vega, for whom I named a lovely species of Solanum a couple of years ago. I am hoping we find Solanum sanchez-vegae on this trip – maybe when we leave Cajamarca for points south. Can’t wait.

Posted on behalf of Sandy Knapp, Museum botanist on field work in Peru.