I am not sure what happened this field trip to Peru – I never seemed to have time to write the blog… but now I am on the plane back to the Museum, there’s not a lot else to do. Maybe I thought my relatively random scrawls about daily events were not necessary, as we had Erica McAlister's partner, Dave Hall, along to help with the driving – he is, after all, a real journalist! But here goes…

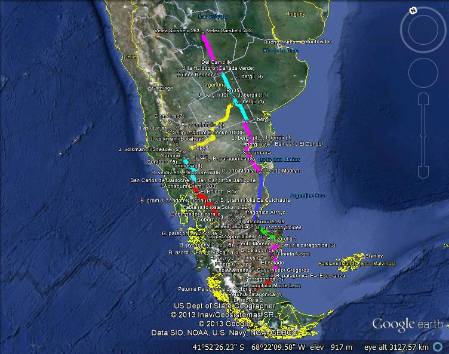

Seeing the coast of Peru from the air reminds one of what an amazing environment we have had the privilege of travelling in - the blanket of fog and cloud on the coast gives way abruptly to the steep slopes of the western slope of the Andes, then you can see the Amazon basin stretching out into the distance.

Waving goodbye to Peru from the air.

The fog is the reason that Lima has been grey, misty and just plain not very nice for the last week while I have been negotiating export permits, giving talks and working the collections. The cold Humboldt Current flows north along the coast, combined with the rain shadow from the Andes, this creates the dry coastal deserts where many of the wild tomato species grow. In the winter, the fog comes in to the coast, and in El Niño years (of which 2014 is predicted to be one) it rains – seems like a good thing, but these strong rains cause incredible devastation in a landscape that is not used to having any precipitation at all.

The species of wild tomatoes are concentrated in these coastal deserts – chief among them and a real find for us between Chiclayo and Trujillo was Solanum pimpinellifolium – the wild ancestor of our cultivated monsters. The fruits are tiny and bright red – each has only 5-10 seeds – tomatoes in miniature!

The plants grew along a wind break by the edge of the Panamerican Highway – but the desolate landscape did not stop our intrepid entomology team of Erica and Evelyn Gamboa (a student from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos who came with us – a great help and good companion!) from sampling to their hearts content.

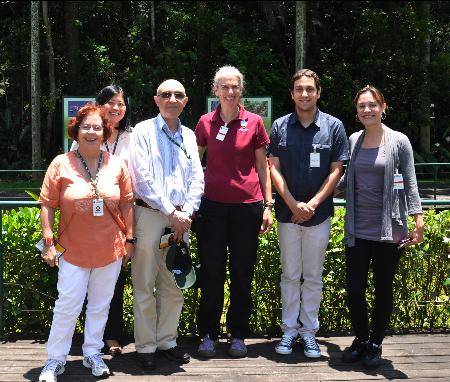

This field trip was another in the series we are undertaking for the Natural Resources Initiative, collecting insects from wild relatives of tomatoes and potatoes in Peru. We didn’t do well with potatoes on this trip – not a single plant did we see – but the tomatoes were in fine form. Not going up the valleys from the coast, as it has been a very dry year – this was a bit disappointing. But the vegetation soon made up for it. For the first couple of days out of Trujillo (a town about 10 hours drive N of Lima) we were joined by my colleague and friend Segundo Leiva of the Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego.

Segundo and his family kindly took us out for a lovely meal in town before we went – much needed after the long drive up the Panamerican highway from Lima!

Segundo specializes in other genera of Solanaceae – and we had an amazing harvest of Browallia – several new species, but we missed seeing Browallia sandrae, it was just too dry. The photo I posted before we left was in fact NOT the species he named for me but ANOTHER new one!! The diversity of this small genus in these dry valleys on the western Andean slopes is quite incredible.

This tiny species with white flowers was growing on a bare road bank, right next to an even tinier one with purple flowers – names needed for both!

One of our targets for this trip was the valley of the Río Marañon – a deep, dry valley where Solanum arcanum, another wild tomato species, grows. The Marañon is said to be the source of the Amazon – it flows north for hundreds of kilometres, then turns to the east at about Bagua, where it then joins up with other large rivers from Ecuador and Peru. Along its journey from the highlands it travels through as many different habitats as there are in Peru – glacial valleys, dry cactus scrub, paddy rice, lowland rainforest. The descent into the Marañon valley from Celendín is billed as a heartstopper – I had been on this road in the 1980s, but didn’t really remember much. Why not I wonder! It was amazing…

The road is narrow and corkscrew-like – Erica drove it and she was amazing, I’m not sure I could have done it… the drop from top to bottom is more than 2,000 metres, I think that’s almost as deep as the Grand Canyon, but not quite…

The sign says “Slow traffic keep right” – keep right? There isn’t anywhere to go to the right but over the edge!

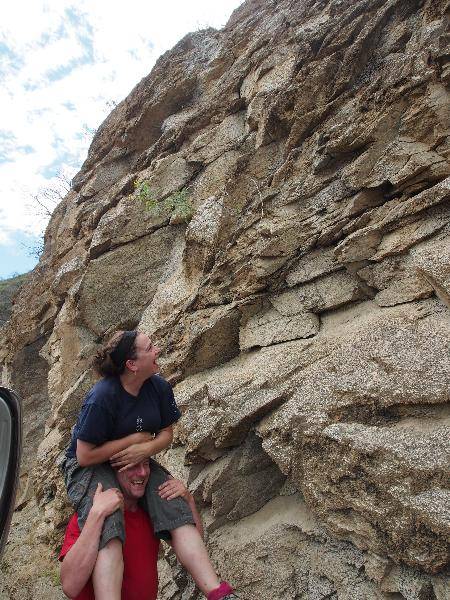

On the dry cliffs we indeed found Solanum arcanum, hanging on for dear life. Novel collecting methods were needed, given the narrowness of the road and the steepness of the cliffs...

Wild tomatoes are woody at the base, but grow new herbaceous stems every year it seems. Even our cultivated tomatoes would be short-lived perennials if we didn’t have such harsh winters.

We had a day off – to go and see the amazing ruins of Kuélap, fortress of the Chachapoyas. The Chachapoyas were a people who lived in the northern mountains before the Incas, were conquered by the Incas, and adopted many Inca customs while blending them with their own culture. The archaeological sites were hidden for a long time – they are high in the mountainous valleys, in forest and very difficult to access. A wonderful museum in the town of Leimebamba displayed the mummies found high above a lake – hundreds of ancestors preserved for veneration by the Chachapoyas; it is amazing that they were preserved in such an environment.

Kuélap itself is reached by a winding dirt road, some 40km from the main highway – not many people there! The structures are different to those Inca ruins in Macchu Picchu and further south – but every bit as impressive. The fortress itself sits atop a ridge and from far away just looks like a layer of rock, unless you know it is there. We had it to ourselves, except for a few other hardy souls and a couple of llamas.

Some parts of the site have been restored using the original stones – there were more than 200 of these round dwellings inside the fortress walls.

Almost as exciting for me was finding Solanum ochranthum growing in the trees around Kuélap – it is a distant tomato relative with very large fruits (up to 5cm across). The fruits have a very thick rind (about half a centimetre) but the pulp is green and sweet. The rind though is terribly astringent! It was all over the area and we sampled it several times the next day.

Solanum ochranthum and its relative Solanum juglandifolium are both large woody vines that can reach the canopy of cloud forest – very unlike the wild tomatoes from the desert!

As is often the case in field work, plans change from day to day. We had thought of going back through the Marañon, but decided instead to cross it further north, near its junction with the Río Utcubamba near the town of Bagua and come down the coast from Chiclayo. The river is a much bigger beast this much further north, and these valleys are not as steep – paddy rice was being cultivated in the flat river terraces – it was hot and sticky down here in the relative lowlands.

The way back to the coast went up and over the Abra de Porculla – a famous collecting locality from the last century. I was really glad we went that way – a new range extension for yet another wild tomato species, Solanum neorickii, in the rocky cliffs ascending the pass. Solanum neorickii has one of the widest distributions of any wild tomato, from southern Peru to southern Ecuador, but collections are scattered in dry valleys and these new records will help us to predict better its actual distribution and its relation to the environment.

Solanum neorickii has the smallest flowers of any wild tomato species and the style is always included within the anther cone (compare this with the picture of Solanum ochranthum above). It is almost entirely self-fertilizing (or so we suspect), which might account for its broad distribution north to south.

Cresting the pass we had an amazing sight of a cloud bank – it began at approximately 2,000m and dissipated at exactly 1,000m elevation – it was as if we had driven through a layer on a layer cake! In the cloud on the way down we found Solanum habrochaites – quite possibly my favourite wild tomato.

Solanum habrochaites seems to be able to grow almost everywhere - the dry coastal valleys, the fog forests of the coast, inter-Andean valleys… Its ecological tolerances must be huge.

Of all the wild tomato species this is the one I am really interested in from an ecological perspective and where the ability to sequence DNA that our genetic resource permit allows us will reveal new information. Collecting Solanum habrochaites and its associated insects in such different places raises all sorts of questions:

- Are these populations very distinct in terms of genetics?

- How do their associated insects differ with habitat?

- Are there subtle differences in form of plants that we can measure from our herbarium specimens and then correlate with differences in the genome?

And the list goes on… this is why field work is so important. Without seeing this species in the field many of these ideas might not have occurred to us – now we have some new things to test once we are back in the Museum and get all the samples sorted.

We broke our long drive down the coast with a stop at the museum in Lambayeque devoted to the incredible finds of Sipán, a famous burial site of the Moche culture. The Moche people inhabited the coastal deserts before the Inca, and buried their kings with phenomenal treasure – gold and silver work of exquisite quality, huge bead collars and an amazing array of artefacts rivalling those found in the pyramids of Egypt. The museum was a wonder – the visitor descends through the finds just as the archaeologists found them, and the sheer number of things on display is staggering. No photos allowed, so you will just have to look it up on line or, even better, visit Peru! The discovery of the tomb of the Lord of Sipán is a real life Indiana Jones adventure, and its preservation for posterity is down to the energy of Walter Alva, a Peruvian archaeologist whose work prevented these treasures from all going into the hands of private collectors who bought them on the black market.

Museum of the Royal Tombs of Sipán.

Coming into Lima was an adventure in itself… We looked like mad for tomatoes along the road, but they were gone… The traffic though was something else. Imagine the M25 or a major ring road with bumper to bumper traffic, lorries, cars etc., then add mototaxis, people selling things from the central reservation and drivers trying to cut perpendicularly across the main flow. All accompanied by a concerto of horn tooting and brake squealing. It is amazing there are not more accidents! But we made it.

He is a taxi so he can go wherever he wants!!

Erica and Dave left for London, while I sorted out the dried plants, export permits and all the other things one needs to do at the end of a field trip. I always have mixed feelings about this time – on the one had I enjoy spending time with Peruvian colleagues and I actually really like Lima, grubby as it is, but on the other hand, there are a lot of things waiting for me back in London...

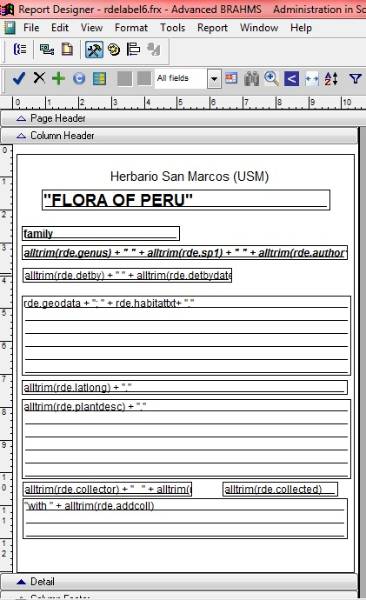

So another field trip ends – but as usual, it is only another beginning. I will look forward to seeing the specimens we collected, finding out how the insects differed from place to place and combining these results with those from previous field work on the Initiative. We are now getting enough collections to begin to formulate the next set of projects and to think about the papers we will begin to write using these data. We need some time in the Museum now though, sorting out what we have, and then planning the next trip. Field work is an essential part of understanding how the natural world works – seeing it in action brings the collections we already have to life and generates new questions. It always seems like the more you know, the more you realise how little you really do understand!