After all the talk (and film) about the bee-fly and its long proboscis, I thought you should see the actual insect with the longest proboscis in terms of body size - and of course it is a group of fabulous flies - but that goes without saying! So this week’s blog is all about tangle-veined flies, known as Nemestrinidae.

Nemestrinus bombiformis - showing their lovely wings

What has sparked this blog piece was my finally looking through some recent material collected by a colleague Duncan, one of the other fly curators. He has recently returned from Morocco with loads of my flies - the chunky ones including bee-flies, robberflies and these tangle-veined flies. This reminded me about some that had been collected by another colleague in South Africa. So I went to find where I had stored them, and track down all the literature I would need to identify it. But along the way I became quite obsessive about this little family.

So what are these tangle-veined flies? There are about 300 species worldwide in 23 genera, although none, sadly, are found in the UK. There is still much confusion about this family and the subject is crying out for a major overview. These flies are most closely related to the hunchback flies also known as the spider-killing flies (Acroceridae); and as with the Bee-flies and the hunchback flies, the larvae of this family are also endoparasites.

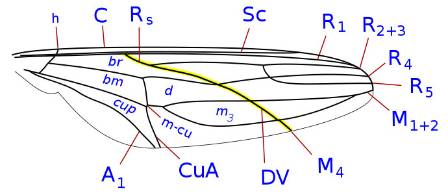

The adults are generally medium-to-large flies, often with hairy bodies, but all with a complicated vein pattern on their wings.

They are often brightly coloured, but if you look through the collection you will see many covered in pollen, which gives an indication to what the adults are feeding on! Within the family, some species have atrophic mouthparts - that is, they are no longer there or they are non-functional but most have the characteristic tube-like proboscis, which is often very long.

In the collection at the Museum we have 149 species registered from 14 different genera. The Museum houses about half the number of described species of Nemestrinidae.

We are always trying to increase the collections and enable greater access to them. There is not much point to a collection that is hidden away, and we are gradually enabling more of our collections be digitised for online access, as well as tweeting and blogging about them informally.

Not much is really known about this family (a common theme across the whole of Diptera). We do have some fossils - the oldest recorded is from the Middle-Upper Jurassic Karabastau Formation (a geological formation in Kazakhstan; about 160 to 145 million years ago) but when it comes to the extant flies we still have huge gaps in knowledge.

We think all the species across the subfamilies have hypermetamorphosis larvae - that is, the larval stages go through distinctly different phases of their development. And all of the family parasitise other insects (as far as we know). The female is quite extraordinary, as she can lay several thousand eggs in her lifetime on plants and surfaces that are generally off the ground (a housefly only lays about 500).

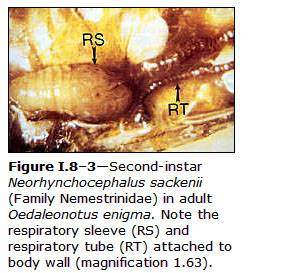

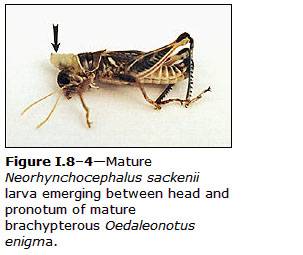

After about 10 days, these will hatch into very mobile larvae. These will disperse readily, often helped by the wind, to seek out their hosts. They can survive for up to two weeks in this state seeking out their hosts. This is just as well as they have very active hosts - the larvae of subfamily Trichopsideinae are all parasitoids of grasshoppers; the Hirmoneurinae seek out scarab beetles; and with Atriadopsinae it’s bush crickets.

(Images taken from US Department of Agriculture website)

Within our collection we have four subfamilies represented. There is still discussion about how many subfamilies there are and where the different genera should be placed but I will work on the basis of the following groupings for the moment.

- Atriadopsinae

- Atriadops

- Ceyloniola

- Nycterimorpha

- Nycterimyia

- Hirmoneurinae

- Hirmoneura

- Nemestrininae

- Moegistorhynchus

- Nemestrinus

- Prosoeca

- Stenobasipteron

- Stenopteromyia

- Trichophthalma

- Trichopsideinae

- Fallenia

- Neorhynchocephalus

- Trichopsidea

There are some nice features to tell these subfamilies apart. Being me I have to get genitalia into a blog post somewhere, and for a change it is the female genitalia that holds the key to their ID - or rather, it is her ovipositor (egg-laying tube). The subfamilies Hirmoneurinae and Nemestrininae have telescope-shaped ovipositors that have retractile segments like a pump-action egg-laying machine! The other two subfamilies have sabre-shaped ovipositors, which bare two very long and slender valvulae (a scientific term for Diptera lady bits) from which she shoots her eggs.

But there is a more obvious way the subfamilies can be split apart: by their mouthparts.

Hirmoneura anthracoides

They vary from rudimentary, reduced, short, medium and long - in some instances very long. In fact one species of Nemestrininae called Moegistrorhynchus longirostris has the longest mouthpart in relation to body size of any insect.

When I came across these in the collection I actually squealed in excitement. They have such a long proboscis because of the flowers they feed on - plants with very long necks; mainly the orchids and the irises. They do not generally fly with them out in front of them but held underneath their body:

In South Africa there are a lot of very long-tongued flies (as they are known). There are also horseflies that have evolved from blood sucking to nectar feeding, with the development a disproportionately long mouthpart. Philoliche longirostris (= "long mouth"... no point having different names if it the best descriptor!) is one such horsefly, and Dr Shelah Morati has a fab website with some amazing images of them.

The tangle-veined flies are also are adapted to feeding from long-necked plants.

These irises seem to have 'landing strips' for flies

The irises in the photo above seem to have landing strips that help guide the fly in. Work conducted by Dennis Hansen when he was at the University of Kwazulu-Natal discovered that if you paint over these strips, the flies cannot find the nectaries at the base of the tube!

And many people have studied these groups, as they are amazing examples of co-evolution with very good models correlating corolla (the petals of the flower) length and proboscis, including work by Dr Bruce Anderson at the University of Stellenbosch! Great stuff!

The collection of tangled-vein flies the museum has been static for a while but we are now collecting more in South Africa, and recent additions to the collection prompted me to recurate the specimens. The drawers were shallow (resulting in many of the pinned specimens being put in in a jaunty angle) and they were also on slates.

Old-style storage

So after a week or so of updating the database and checking out any changes in nomenclature I have transferred the little cuties into new trays with spanking new labels into new deeper drawers. Job done!

New-style storage