Long time, no blog. However, I have just been inspired. It is the 100th anniversary of the Piltdown Man hoax this week, when the deliberate amalgamation of a human skull and an orang-utan jaw was used to bamboozle the scientific community into thinking they had at last found the missing link. It has been described as one of the greatest hoaxes of all time. But no! I cry. There is something much more important than the mere amalgamation of a human skull and an orang-utan jaw to create the supposed missing link – yes, it is the Piltdown Fly!

This was such a good story that when the truth was uncovered, or rather comically stumbled upon, it made the papers. Nice to see that even the Sun was amused by such humble creatures as flies (I will explain all later).

So let me begin…it starts with a species that was first described by Johan Fabricius (the daddy of insect naming) – a Danish entomologist and student of Linnaeus. From 1792 to 1799 he published many volumes of Entomologia systematica emendata et aucta of which the 1794 volume included a description of what was then thought to be a small species of fly closely related to our common house flies (Muscidae). It was described as Fannia scalaris and is more usually known as the latrine fly (can you guess where it spends most of its time?). These are now in their own family, the fannidae, and are distinguished from the house flies that most of you know, and for some unknown reason, dislike, by being smaller and more slender. I have to say I don’t find the genus name particularly attractive…

Fannia scalaris (this specimen is completely covered in mites! (image by Nikita Vikhrev))

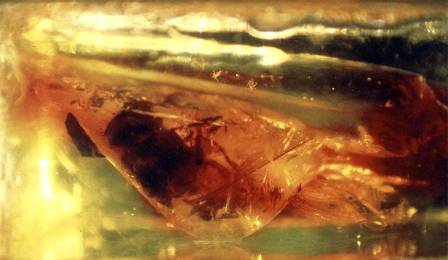

The specimen that caused all the problems, however, was one in amber. Flies in amber are great, and there is a very nice collection here at the Natural History Museum. Sadly, it belongs in another department and for some reason they won’t let me have it...

The specimen in question was originally acquired by the Natural History Museum by the very distinguished German scientist Friedrich Hermann Loew. Now, he was a very eminent entomologist, but was not known for his knockabout sense of humour. His Wikipedia page (which therefore must be true) has a lovely description of his character:

‘Loew was a Lutheran protestant, whose motto was "Gott Helfe" (God may help). Loew was an obsessive worker. Something of his nature can be judged from his refusal to eat warm food while he paid off the loans incurred during his education, and from his extraordinary calligraphy, with its machine-like precision. There is never any difficulty with reading a Loew label, characteristically justified to the side margins.'

William Loew – don’t make them like that any more sadly…(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Loew)

But this was not just any old fly in amber. This specimen tricked the scientific community into believing these advanced flies were around 38m years older than they were! Advanced flies? I will explain.

Diptera are fairly old group of animals. In terms of insects they are relatively advanced, turning up about 220 million years ago. And after they arrived on the scene they had two further periods of exciting evolution. After the initial development of the one-winged flying creatures – with lovely, long antenna and generally long and slender bodies – they got chunkier. About 180m years ago the lower Brachycera came along – and these include the amazing robberflies, beeflies and horseflies – all marvellous looking creatures.

Then about 65m years ago, along came the Schizophora. The Schizophora are truly remarkable for how they exit a puparium. The blow their head up into a massive balloon, which pops open the puparium along a line of weakness. This balloon then deflates and sets to become a distinctive diagnostic ridge on the front of their head (the ptilinial suture) – very cool.

Check this link to see a fly inflating it’s ptilinium: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SR0Cko6z5jM

Now within the Schizophora are the flies that everybody recognises – the calyptrates. You may not know the name but it includes families such as the houseflies, botflies and fleshflies – in fact all the bristly ones that are generally large and robust. The oldest calyptrates found in amber were the Anthomyiidae (a mixed bunch of flies that have a range of habits including being root pests) which are 40m years old, with the Muscidae evolving within a comparable time period.

Then along comes this little fly in amber.

The Piltdown Fly

Lowe described this specimen in 1850, but it was not really looked at again for another 70 years. In 1922, with the specimen now in the grubby hands of The Natural History Museum, the fly was critically examined again by German biologist Willi Hennig.

Looks trustworthy enough…

Willi Hennig founded what is now described as cladistics- that is phylogenetic relationships of species (how similar species are to each other). When he described our subject as Fannia scalaris (the latrine fly) he did ponder whether it was a fake or not at the time, as if this were true it meant that this species had not evolved in 38m years. But he did not raise any concerns and eventually published. Indeed, the fly was soon to be cited as a good example of evolutionary stasis (nothing changing).

Role forward to 1993. A young curator at the museum. A slightly dodgy light source for his microscope (it was overheating). What could have resulted in one of the museums ‘treasures’ being irreparably damaged instead led to the discovery of one major piece of fraud!

Dr Andy Ross saw that the amber had cracked slightly along a fissure and realised that the specimen was not what it seemed! Infact what the forger had down was to split the amber in half, carve out a small inclusion, place the specimen in this and then reseal with resin the amber. Simple. Clever. And fooled everyone for years! Even modern day techniques would be hard pressed to realise that this was a fake.

There were some clues though such as the damaged abdomen but hey, this can (and was) ignored in the excitement of the moment.

So this specimen has lost its scientific credos but has become all the more notorious because of this. When the discovery of it being a fake was acknowledged, even the popular press were covering it:

And this one from the Daily Telegraph:

And even in the International press…

So move over Piltdown Man: there is a new hoaxer in town. We still don’t know who did it, what motivated them etc but there is a final comment to make in the fact that Hennig’s paper was published on the 1st of April – make of that what you will!