This week one of our academic visitors Hitoshi Takano shares the trials and tribulations of fieldwork, in one of the most hostile and unforgiving places in the world, Africa. But aside from the hardships of fieldwork it is also a beautiful and rewarding place with nature at its rawest and wildest. And, there are thousands of beetles!

However, there appears to be a distinct lack of any evidence of beetle collecting, but here’s a black and white Colobus monkey. Magombera Forest, Tanzania, just to make up for it – and no, HT didn’t bring it back to the Museum for closer study.

In HT’s own words: “Did I really spend all that time just standing in the sun wielding a butterfly net or slumped next to a light trap with a bottle of whisky? I also have a total of zero beetle pictures - it seems I stick them into a tube of alcohol before I even get the chance to take a photo. Note to self for the future - more science and beetle photos!” Yes, more beetles please!

Taking part in fieldwork can often highlight the degradation of habitats, or even countries. When HT went on fieldwork to Sierra Leone this was immediately apparent. Sierra Leone is the world’s worst off nation, after nine years of civil war ending in 2000, it is not jus the economy and the peoples that are affected, it is also the natural environment. After a failed attempt to track the pygmy hippo (one of Africa’s many endangered species whose populations are under threat from deforestation and poaching), he tells this story:

“…with an outdated guide to the local mammal fauna, we headed for a locality in ‘impenetrable’ Sierra Leone. We soon understood that this habitat could no longer support a viable population of hippos. After years of civil war, mass deforestation, and farming, the landscape was barren; we couldn’t even pitch our hammocks. Forget hippos, there weren’t even trees, which meant the breaking of the cardinal Ray Mears rule of never sleeping on the ground in the tropics…. But on a positive note, unlike some virgin tropical Africa explorers we didn’t emerge from the jungle with our stomachs in a bag and an unknown virus rioting through our veins! Another of our research sites was more positive, the Outamba-Kilimi National Park had good populations of chimpanzees and elephants, and despite unseasonably long periods of torrential rainfall, there was an abundance of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera.”

So, to get back to beetles, here are some photos of fieldwork, this time in Tanzania.

Setting up the light trap at dusk, Mwanihana peak, Udzungwa Mountains

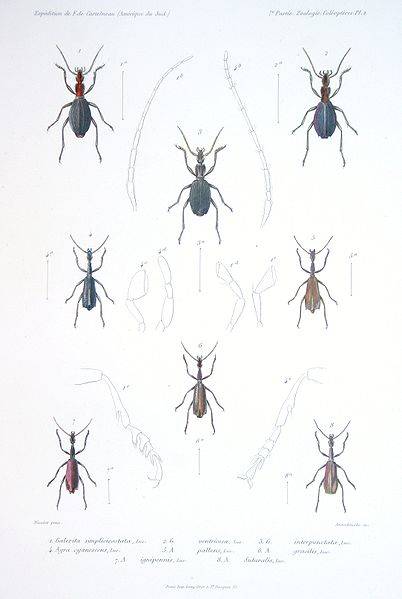

Dung baited pitfall trap (collecting Scarabs which are very good indicators of ecosystem fitness), Nguru Mountains (and yes, entomologists do get a bit obsessed with poo, though we are most definitely not 'anally retentive'!)

Here is HT (on the left) employing the sophisticated fieldwork method of grubbing about in elephant dung with some sticks, looking for beetles...

All good stories, and hard days' fieldwork, end on a sunset, and perhaps a bottle of whisky!

Nguru Mountains, Tanzania

Next time, let's talk about love...