It’s Science Uncovered time again beetlers! We can’t wait to show off our beetles to the thousands of you who will be visiting the Natural History Museum on the night. We'll be revealing specimens from our scientific collections hitherto never seen by the public before! Well, maybe on Monday at the TEDx event at the Royal Albert Hall we did reveal a few treasures, including specimens collected by Sir Joseph Banks and Charles Darwin, as seen below.

Lucia talking to the audience of TEDx ALbertopolis on Monday 23rd September.

Lydia and Beulah spanning 250 years of Museum collections at TEDx Albertopolis.

Lydia and Beulah spanning 250 years of Museum collections at TEDx Albertopolis.

Last year we met with about 8,500 of YOU – so that’s 8,500 more people that now love beetles, right? So, as converts, you may be coming back to see and learn some more about this most speciose and diverse of organisms or you may be a Science Uncovered virgin and no doubt will be heading straight to the beetles (found in the DCII Cocoon Atrium at the Forests Station).

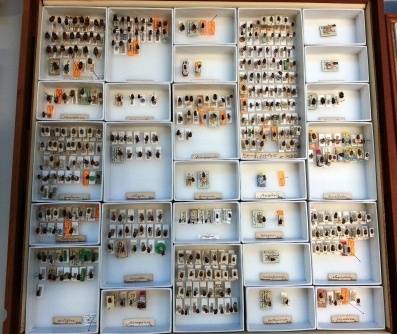

This year the Coleoptera team will be displaying a variety of specimens, from the weird and wonderful to the beetles we simply cannot live without! Here’s what the team will be up to...

Max Barclay, Collections Manager and TEDx speaker

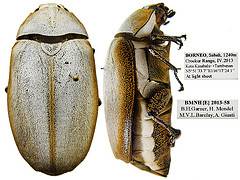

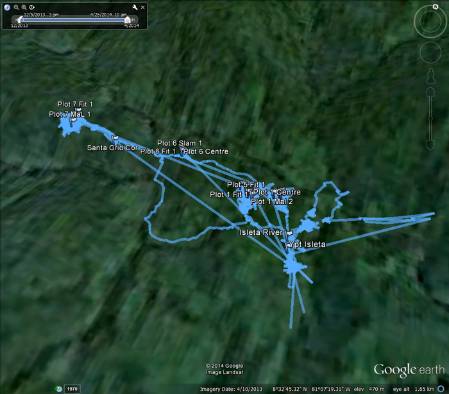

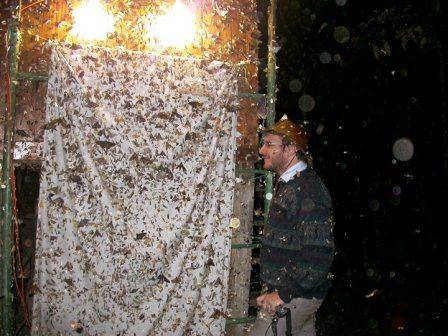

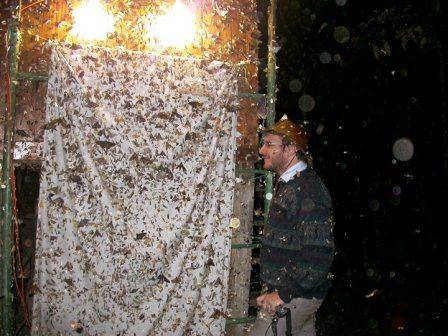

For Science Uncovered I will be talking about the diversity of beetles in the tropical forests of the world. I have spent almost a year of my life in field camps in various countries and continents, and have generally come back with thousands of specimens, including new species, for the collections of the Natural History Museum. I will explain how we preserve and mount specimens, and how collections we make today differ from those made by previous generations.

Crocker Range, Borneo - it's really hard work in the field...but, co-ordinating one's chair with one's butterfly net adds a certian sophistication.

The Museum encourages its staff to be respectful of and fully integrate with local cultures whilst on fieldwork. Here is Max demonstrating seemless cultural awareness by wearing a Llama print sweater in Peru.

I will also talk about the Cetoniine flower chafers collected and described by Alfred Russell Wallace in the Malay Archipelago, and how we recognise Wallace’s material from other contemporary specimens, as well as the similarities and differences between techniques used and the chafers collected in Borneo by Wallace in the 1860s, Bryant in the 1910s, and expeditions of ourselves and our colleagues in the 2000s.

Lydia Smith and Lucia Chmurova, Specimen Mounters and trainee acrobats

As part of the forest section at Science Uncovered this year we are going to have a table centred on the diversity of life that you may see and hear in tropical forests. Scientists at the Natural History Museum are regularly venturing out to remote locations around the world in search of new specimens for its ever expanding collection.

L&L acrobatic team on an undergraduate trip to Borneo with Plymouth University.

Maliau Basin, Borneo: Lucia injects some colour into an otherwise pedestrian flight interception trap

We will be displaying some of the traps used to catch insects (and most importantly beetles!) along with showing some specimens recently collected. We will also have a sound game where you can try your luck at guessing what noises go with what forest creatures. Good luck and we look forward to seeing you!

Hitoshi Takano, Scientific Associate and Museum Cricketer

Honey badgers, warthogs and Toto - yes, it can only be Africa! This year at Science Uncovered, I will be talking about the wondrous beetles of the African forests and showcasing some of the specimens collected on my recent fieldtrips as well as historic specimens collected on some of the greatest African expeditions led by explorers such as David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley.

Museum cricket team, The Archetypes (yes, really!). Hitoshi walking off, centre field, triumphant! Far right, Tom Simpson, Cricket Captain and one of the excellent team organising Science Uncovered for us this year.

.JPG)

Mount Hanang, Tanzania: Jungle fever is a common problem amongst NHM staff. Prolonged amounts of time in isolated forest environments can lead to peculiar behaviour and an inability to socialise...but don't worry, he'll be fine on the night...

There are more dung beetle species in Africa than anywhere else in the world - find out why, how I collect them and come and look at some of the new species that have been discovered in the past few years!!

Beulah Garner, Curator and part-time Anneka Rice body double

Not only do I curate adult beetles, I also look after the grubs! Yes, that's right, for the first time ever we will be revealing some of the secrets of the beetle larvae collection. I can't promise it will be pretty but it will be interesting! I'll be talkng about beetle life cycles and the importance of beetles in forest ecosystems. One of the reasons why beetles are amongst the most successful organisms on the planet is because of their ability to inhabit more than one habitat in the course of their life cycles.

Crocker Range, Borneo: fieldwork is often carried out on very tight budgets, food was scarce; ate deep fried Cicada to stay alive...

Nourages Research Station, French Guiana: museum scientists are often deposited in inacessible habitats by request from the Queen; not all breaks for freedom are successful.

On display will be some horrors of the collection and the opportunity to perhaps discuss and sample what it will be like to live in a future where beetle larvae have become a staple food source (or entomophagy if you want to be precise about it)...go on, I dare you!

Chris Lyal, Coleoptera Researcher specialising in Weevils (Curculionidae) and champion games master

With the world in the throes of a biodiversity crisis, and the sixth extinction going on, Nations have agreed a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity. The first target is to increase understanding of biodiversity and steps we can take to conserve it and use it sustainably. That puts the responsibility for increasing this understanding fairly and squarely on people like us. Now, some scientists give lectures, illustrated with complex and rigorously-constructed graphs and diagrams. Others set out physical evidence on tables, expounding with great authority on the details of the natural world. Us – we’re going to play games.

Ecosystem collapse! (partially collapsed).

Thrill to Ecosystem Collapse! and try to predict when the complex structure will fall apart as one after another species is consigned to oblivion. Guess why the brazil nut tree is dependent on the bucket orchid! Try your luck at the Survival? game and see if you make it to species survival or go extinct. Match the threatened species in Domino Effect! Snakes and ladders as you’ve not played it before! For the more intellectual, there’s a trophic level card game (assuming we can understand the rules in time). All of this coupled with the chance to discuss some of the major issues facing the natural world (and us humans) with Museum staff and each other.

Here Chris tells us a joke:

'Why did the entomologists choose the rice weevil over the acorn weevil?'

'It was the lesser of two weevils'

Joana Cristovao, Chris's student and assistant games mistress!

Joana Cristovao, Chris's student and assistant games mistress!

Big Nature Day at the Museum: Joana with a... what's this? This is no beetle!

One last thought, things can get a bit out of hand late at night in the Museum, it's not just the scientists that like to come out and play once a year, it's the dinosaurs too...

We look forward to meeting you all on the night!